After Almost 500 Years, the World’s Oldest Social Housing Complex Is Still Going Strong

The rent of less than one Euro per year at the Fuggerei, located in Augsburg, Germany, hasn’t changed either

In 1516, Jakob Fugger the Rich, a wealthy merchant in Augsburg, Germany, had a charitable idea. He wanted to create a place for the city’s needy Catholic workers, where they could live together debt-free, without the stress of trying to get by in an expensive place on a too-low salary. Construction began immediately on what Fugger called the Fuggerei, a walled town within the city of Augsburg, where for just one Rheinischer Gulden (about .88 Euro today, and around one month’s salary for laborers of the time) per year, residents would get an apartment and the security of not having to struggle for money.

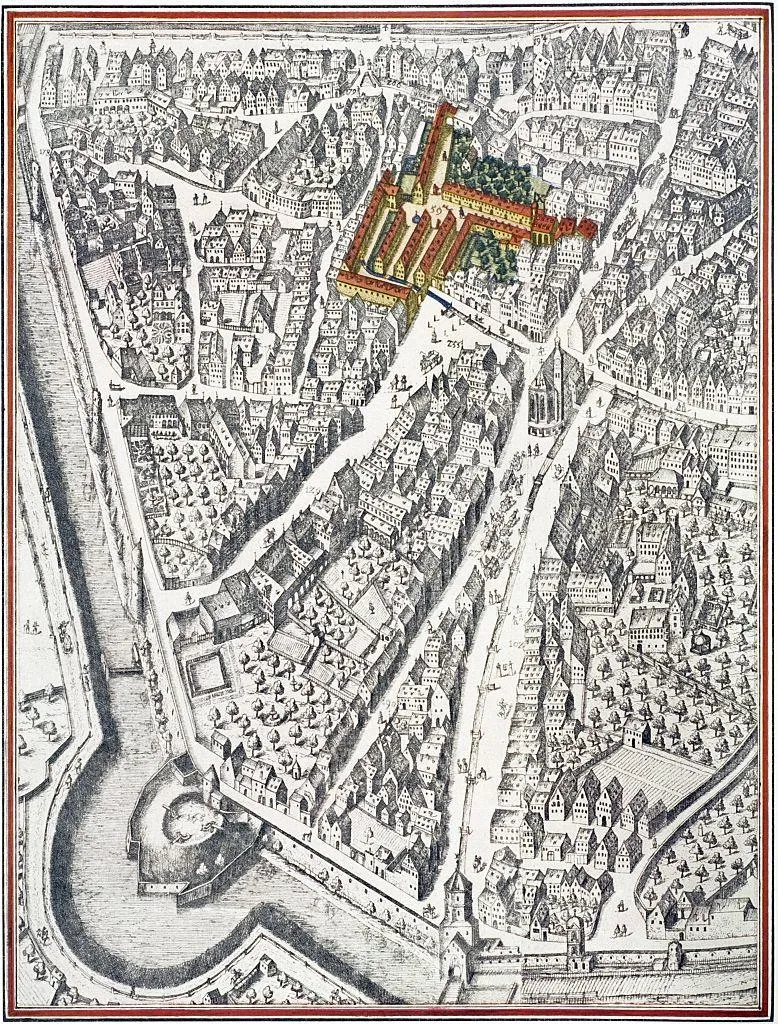

The Fuggerei was designed to maximize the use of its property. Identical red-roofed buildings, all two floors with an apartment on each floor, were built along eight straight lanes with seven gates in the walls. By 1523, 52 houses were built, and the complex continued to expand with more homes, a town square, and a church.

There were conditions to living in the Fuggerei, though. You had to be Catholic with a low income and no debt, and be a respectable member of society. You had to say three prayers per day for the Fugger family. You needed to be back home by 10 p.m., when the town gates locked, or you’d have to pay a fee to get in. Fugger donated the complex to the city in 1521, with the understanding that the Fugger family would continue to own and run it, and that the Fuggerei was meant to last forever with no changes to the rent, rules and regulations.

Now, nearly 500 years later, the Fuggerei is the world’s oldest social housing complex. It houses needy Augsburg residents, who still pay .88 Euro per year—except now there are about 150 residents of all ages and marital status, 67 buildings and 147 500-to-700-square-foot apartments. Interested renters must have lived in Augsburg for at least two years to apply for an apartment. Then, accepted residents still need to follow the original rules from the 1500s, saying three prayers a day (the Lord’s Prayer, Hail Mary and the Nicene Creed) for Jakob Fugger and the current Fugger family owners. Plus, they need to work a part-time job in the community. Resident Ilona Barber, who’s lived at the Fuggerei for five years, works at the tour admission desk, but others may be a night watchman or a gardener.

Those requirements of residency are worth it, Barber says, and don’t have too much of an impact on her life. “Living here has given me peace of mind,” she says. “Before coming here, you don’t have enough money and you have to try to survive paying rent and life’s expenses. But here, you have peace of mind. You can afford things you couldn’t buy before. It’s relaxing.”

Astrid Gabler, who handles PR at the Fugger Foundation, says, “The Fuggerei would like to be a home for its residents, where all can feel safe and secure. But the Fuggerei is more than just a cheap roof over one’s head. Above all, the residents should lead successful lives despite being in need. Residents very often mention that they have at last found peace from their cares and problems here. Some move into the Fuggerei under extreme circumstances, recoup their strength and can move out again after a certain time.”

The Fuggerei has had its share of noteworthy residents over the past 500 years. One was 48-year-old Dorothea Braun, who lived there until her untimely death in 1625. Braun was the first victim of Augsburg’s witch hunts. She lived in the upper level of the gatehouse at Ochsengasse 52 and worked as a caregiver in the Fuggerei’s infirmary. Her own 11-year-old daughter accused her of witchcraft. Braun was tortured until she confessed. On September 26, 1625, Augsburg’s court convicted her, beheaded her, and burned her body.

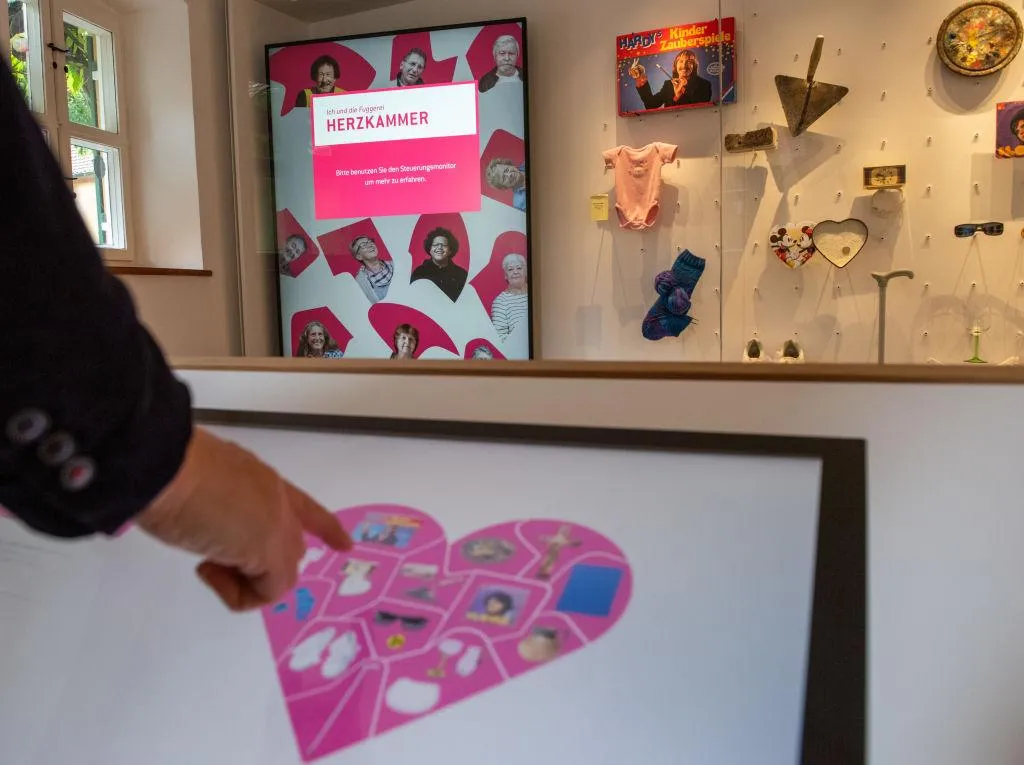

In 1681, Franz Mozart moved into House 14 on Mittlere Gasse. The bricklayer would eventually have a famous descendant—he’s composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s great-grandfather. Franz died in the Fuggerei in 1694. The complex's current most famous resident is a magician named Hardy, who moved there in 2016. Hardy initially took up magic to cure a speech impediment, and has gained fame through his work—but his income still fits in the Fuggerei requirements.

A tour around the Fuggerei today shows visitors not just the historical complex, but also some of the more unique aspects of it, like the doorbell pulls. Every building looks about the same, and the doors are identical, so residents in the past would try to enter the wrong apartment. As a result, each apartment door was outfitted with a wrought iron doorbell pull, every one of which has a different shape to it, so residents could literally feel if they were at the proper door. Visitors can see hand-pump wells residents used starting in the 1700s to get water, some of the original Gothic address numbers from the 1500s, a cast iron fountain from 1744, a school, a hospital, a restaurant and beer garden, and a church.

The Fuggerei complex has three museums. One is a model apartment at Ochsengasse 51 displaying what a fully furnished apartment looks like today. Each apartment has a bedroom, a living room, a full kitchen, and a bathroom with a shower or tub. Apartments on the lower floor have a garden patio space in the backyard, and apartments on the upper floor have use of the attic. Another museum, the official Fuggerei Museum, at Mittlere Gasse 13/14, is a historical apartment. It’s the only apartment preserved in its original condition. The three-room space has exposed timber, a kitchen with a wood burning stove that shares heat with the living room, and a bedroom. Also part of the Fuggerei Museum is a 2006 expansion that discusses the history of the Fugger family and the Fuggerei complex. The third museum opened in 2008: a preserved World War II bunker. The air-raid shelter, inside the Fuggerei walls, was built for residents during the war. The exhibit, “The Fuggerei in WWII—Destruction and Reconstruction,” describes how about 75 percent of the Fuggerei was destroyed during the war, as well as the reconstruction process that followed.

It’s been a complicated task to keep the Fuggerei going throughout its nearly 500-year history. Funding for the complex has transferred a couple times; in the beginning it was funded by an endowment’s interest yields, and since the 18th century, investments in forestry provide the money for maintenance and operation. The Fugger family, now on the 19th generation since Jakob, is still responsible for maintaining the foundation and trust that Jakob established in 1520 when he opened the Fuggerei. Admission conditions and rules have continually been adapted to the unique circumstances of time—now, for example, residents have to hold a part-time job in the complex, and they don't have to pay a fee for coming in after 10 p.m. Plus, there’s an administrative team that needs to attend to current business and residential needs, including social education counseling. According to Gabler, flexibility, commitment and a continuing strict set of rules for residents continue to keep the complex a success.

“The Fuggerei is unique in the world,” Gabler says. “A visit enables a view on a special community and its values. This is an important part of the history in Augsburg and the Fugger family, and the Fuggerei shows their development. Even more, our visitors can experience peace and spirituality.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)