Life Aboard a Renovated World War II Tugboat

With help from friends, a transplanted Philadelphian embarks on a voyage of discovery through Alaska’s waters

:focal(1514x1385:1515x1386)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/c6/c7c66a41-06c3-451a-be01-6b430321ac70/sqj_1607_alaska_boat_01.jpg)

Day One

The morning of our departure I woke in the dark, Rachel and the baby breathing softly beside me. An oval of light worked its way over the knotty pine of the Adak’s stateroom, cast by the sodium floodlights of a herring seiner passing in the channel.

Lying there I could see my upcoming trip projected on the ceiling above: Our World War II tugboat plying Peril Strait, coasting down Chatham, hooking around Point Gardner, then east, past Petersburg, into Wrangell Narrows. And there at the bottom, scattered like diamonds at the foot of the mountain, the lights of Wrangell—and the only boat lift in Southeast Alaska burly enough to haul our floating home from the sea.

It was time. Since buying the Adak in 2011, I had sealed the decks, ripped out a rotten corner of the galley, installed berths, and convinced the engine, a 1928 Fairbanks-Morse, to turn over. But the planks beneath the waterline—these were the mystery that could make or break our young family. Surely the bottom needed to be scraped and painted. I just hoped the teredos, those invasive worms that keep shipwrights in business, hadn’t been having too much of a feast in the ten years since the boat had been out.

I slipped out of bed, made coffee in the galley, and rousted Colorado, our husky-lab mix, for his walk. Frost glinted on the docks. A sea lion, known around the harbor as Earl (my guess is there are about a hundred “Earls”) eyed us warily. Soon the herring would spawn, orange and purple salmonberries would cluster above the riverbanks, and Chinook salmon would return to their native grounds. Pickling sea-asparagus, jarring fish, scraping black seaweed from rocks—all these rites of spring would begin again, rites I’d first come to love when I arrived in Sitka at the age of 19, when I spent nine months living in the woods, independent, self-reliant, and lost. In those months Alaska had planted a seed in me that, despite my efforts to quash it, had only grown.

In 2011 I finally gave in, sold my construction company, back in my hometown of Philadelphia, along with the row home I had been renovating over the previous five years, loaded the dog into the truck and returned to Sitka-by-the-Sea, an island fishing village on the North Pacific horseshoed by mountains, known for its Russian heritage and its remoteness. I took on small carpentry jobs, commercial-fished, and wrangled with a novel I was writing over the long winter nights. A couple of years after moving onto the boat, while moonlighting as a salsa instructor in town, I met eyes in the mirror with a student, Italian on both sides, originally from New Jersey. On a rainy day in that same classroom, I proposed, and we married soon after.

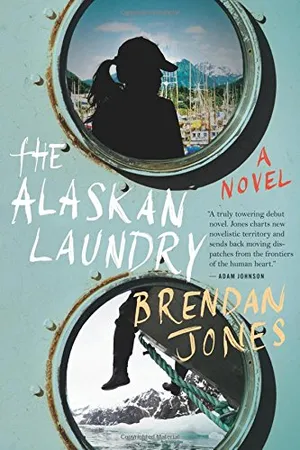

Today we raise our 11-month-old daughter, Haley Marie, aboard the boat. My novel, The Alaskan Laundry (in which the Adak plays a starring role), has just been published. The tug has been good to us, providing waterfront living for the price of moorage; 2,000 square feet of space, much more than we could ever afford on the island; and an office for Rachel, which doubles as a baby nook. But it has also presented challenges, catching fire twice, almost sinking twice, and setting my hair prematurely gray. I still love it—and so does Rachel—its varnished oak interior, Army certifications emblazoned on the timbers, how it scents our clothes with that particular salt-oil odor. Haley, whose stuffed animal of choice is Scruffy the Huffy Chuffy tugboat, falls asleep immediately in the rock of the swell.

*****

This trip to Wrangell would determine the boat’s future. Either we could or couldn’t afford the fixes, simple as that. Rachel and I agreed on a circuit breaker of a number, and the math wouldn’t be difficult, estimating about a thousand dollars a plank. We’d know the moment the boat emerged from the water. And this would only happen if the harbormaster in Wrangell accepted the Adak, not a done deal by any means, considering that the dry dock in Sitka had refused us for being too heavy and for the unknown state of our hull.

I whistled for the dog, and we doubled back. At the boat Steve Hamilton, in his logging suspenders and Greek fishermen’s cap, climbed out from the hatch. I knew his arthritis woke him in the early hours. He had agreed to accompany us on the voyage, along with his son Leroy, 40, who had grown up on the boat, leaving his name etched into the planking, and his grandson Laddy, short for Aladdin, 22. They had all come down on the Ahi, a 40-foot “shadow-tug” that in an emergency would keep us from running aground.

Raised in Alaska logging camps, Steve had owned the Adak in the 1980s, bringing up four children on board. I had done what I could to prepare in advance of his arrival—filling the cylinder water jackets with freshwater to preheat the engine, hosing enough water into the forward tank for doing dishes. But when Steve came in three days before our departure, the serious work began: rebuilding the salt water pump, changing the compressor valves, switching out injectors for the three-phase generator. We’d be joined by Alexander (Xander) Allison, a Sitka seventh-grade language arts teacher who lived on his own 42-foot boat, and former competitive powerlifter Steve Gavin (who I’ll call Gavin to keep it simple), who now clerked for a judge in town while studying to become a magistrate.

“She’s ready,” Steve said across the deck.

I threw on my coveralls, pulled on XtraTufs—milk-chocolate rubber work boots ubiquitous in Southeast Alaska—and dropped through the hatch to lend a hand.

*****

The sun broke cleanly over Mount Arrowhead that morning, so rare in these 17 million acres of hemlock and spruce and cedar, where what islanders call liquid sunshine thuds into the carpet of moss and needles on average 233 days a year. The only frost remaining on the docks was protected in the shadows of the steel posts.

Rachel and Haley stood on the docks as we untied the Adak and prepared to fire the engine. I knew Rachel wanted to come, but she was recently pregnant with our second child, and we had both agreed it would be too risky.

The afternoon before we left, Eric Jordan, a third-generation Alaskan fisherman, and about as salty as they come, reviewed the route with me at his home.

“Of course you’ll hit Sergius Narrows, not with the tide change but with the currents … same with Wrangell Narrows; take it slow in there. Scow Bay is a good anchorage south of Petersburg; you can also drop the hook at the end of the narrows.… Do you have running lights?”

I looked up from the map. “We’re not sailing at night.”

“Look at me, Brendan. This is no joke. Tell me you’ll put running lights on the boat.” I told him I’d put running lights on the boat.

Steve kicked air to the engine and it rumbled to life. (“It’ll rattle the fillings out of your teeth,” a friend once said.) Built in 1928 by Fairbanks-Morse, which specialized in locomotive engines, the beast requires air—without a good 90 pounds per square inch, compression won’t start and the prop won’t turn. Quick story to drive home this point: A previous owner had run out of air while docking the boat in Gig Harbor, Washington. He destroyed eight other boats, and then the dock. Boom.

But the problem we were discovering as we sailed the 500 yards down the channel to the town gas dock was oil. “We’ve got it pooling in the crankcase,” Steve said, watching as Gavin and Xander threw lines to the dock, the workers seemingly paralyzed by this pirate ship drifting toward them. Xander hopped off and made a clean anchor bend on the bull rail, a penchant for neatness I’d come to appreciate, while Gavin, headlamp affixed to his forehead, set to work lugging five-gallon oil buckets onto the deck.

“We could run her at the dock a bit,” Steve said.

“Or we could just go,” I said tentatively.

“We could do that.”

And that’s what we did, gassing up, untying again, and punching her along past the breakwater. Past Middle Island, the farthest the tug had gone since I owned her, past beds of kelp, bullet-shaped otter heads bouncing in our wake. Despite feeling that same cowboy excitement as when leaving on a fishing boat—that zeal for danger and blood and money—now I wished Rachel and HMJ could be here in the wheelhouse, gripping the knobs of the oak wheel, smelling the tang of herring and spruce tips on the water. Steve’s copper wallet chain jangled as he came up the ladder, snapping me from my thoughts. He ran a rag through his fingers. “Crankcase is filling up. Something’s got to be done.”

Friday, I thought. It was because we were leaving on a Friday—terrible luck for a boat. We also had bananas in the galley, a plant on deck, any one of these enough to sink a ship according to the pickled old-timers in their early morning kaffeeklatsches at the grocery store. We were barely out of town and already in trouble.

Leroy tied the Ahi alongside, and Steve detached the air hose from the compressor, screwed on a section of copper pipe, and blew air into the crank pits. The oil pressure didn’t drop.

We decided to stop early, with plans to troubleshoot in the morning. It drizzled as we dropped anchor in Schulze Cove, a quiet, protected bight just south of the rip of Sergius Narrows. Gavin showed me a video he had taken earlier that afternoon from deck of humpback whales bubble-net feeding. Magnificent. I checked the GPS. We had gone 20 out of 200 miles.

I fell asleep with a dog-eared manual from 1928, using a fingernail to trace the path of oil through the engine on the diagrams of its thick-stock pages, knowing if we couldn’t figure out the oil situation, we’d have to go home.

Day Two

The next morning we took apart the oil pump.

Let me revise that. Steve and Leroy bantered while one held a pipe wrench and the other unscrewed, breaking down the oil pump while I held a light and furnished tools. When the engine ran in forward gear, the pump stalled. When it ran in reverse, things worked fine. Leroy, worrying an ever present stick of black licorice, suggested we just go backward every 20 miles. Funny.

Frustrated, I went to the bow to make sure the generator, powering the electrical system on the boat, had enough diesel. A few minutes later Leroy held something in the air. “Check it out. Old gasket caught in the valve.” Back at the pump Steve was smiling. “Too early to tell,” he shouted over the engine, “but I think we might have ourselves an engine.”

We lined up the boat to go through Sergius Narrows, a dangerous bottleneck of water where the tide rips. About 50 otters floated on their backs, fooling with mussel shells as gulls floated nearby for scraps. Cormorants on a red buoy appeared incredulous as we coasted by. “Well I’m just tickled,” Steve said after checking the oil reservoir. “We’re back in business.”

Our second night we anchored in Hoonah Sound, a stone’s throw from Deadman’s Reach—a section of the coast where, as the story goes, Russians and Aleuts died from eating tainted shellfish. Fucus seaweed glistened in the white light of our headlamps. Driftwood bleached bone white was scattered along the beach. Xander pointed out where he had shot his first deer, at the top of the slide, just above the tree line.

We needed a light so other boats could see us in the dark. I went out in the spitting rain and used a role of plastic wrap to tie a headlamp to the mast, then pushed the button. Voilà! A mast light. Eric would be proud. Kind of.

In the salon we lit a fire in the woodstove and dumped fresh vegetables Rachel had sealed and frozen into a cast-iron pan, along with burger, taco seasoning, and cormorant we had shot earlier in the season. Water darkened with wind as we ate, the seabird tough and fishy. The anchor groaned, and we all went out on deck into the blowing rain.

We were stuck in a williwaw, the wind whipping off the mountain, bulldozing us toward deep water, the anchor unable to hook into the sandy bottom. We were—and this is one of the few sayings at sea that is literal—dragging anchor.

I woke continually that night, watching our path on the GPS, imagining contours of the bottom, praying for the anchor to snag on a rock, going outside to check our distance from the beach, and talking with Xander, who knew more about such things than I and reinforced my fretting.

None of us slept well at Deadman’s Reach.

Day Three

Katie Orlinsky and I had a plan. The Smithsonian Journeys photographer would fly into Sitka, board a floatplane, and we’d coordinate over VHF radio to find a rendezvous point where she could drop out of the sky, land on the water, and climb aboard the tug. Easy. Like all things in Alaska.

That Sunday morning, with the wind blowing 25 knots at our back and the sun lighting our way, we gloried in a sleigh ride down Chatham Strait, just as I had imagined. Gavin and Xander glassed a pod of orcas, the boomerang curve of their dorsals slicing through the waves. I cleaned oil screens in the engine room, enjoying how the brass gleamed after being dunked in diesel.

Then the pump bringing in seawater to cool the engine broke. The sheave, a grooved piece of metal connecting it to the engine, had tumbled into the bilge. The boat drifted dangerously, the Ahi not powerful enough to guide us in the heavy winds.

We (meaning Steve) rigged up a gas pump, using a rusted sprocket to weigh down the pickup hose in the ocean. “Time to go pearl diving,” he announced. I followed, confused.

In the engine room, a yellow steel wheel the size of a café table spinning inches from our heads, Steve and I laid on our stomachs, dragging a magnet through the dark bilge. Nails, wire clamps, and a favorite flathead screwdriver came up. Then the sheave. He tapped in a new core (salvaged from the sprocket) and re-attached the belts.

Katie—Xander hadn’t heard from her pilot on the radio. I checked my phone, shocked to find reception. Twelve missed calls from her. No way her floatplane could land in six-foot waves. Instead, after doing a few flyover shots, the pilot dropped her about ten miles south, in cheerily named Murder Cove.

A few hours later, after rounding Point Gardner, I untied the skiff and set off in the open ocean, eyes peeled for Murder Cove. And there she was, a small figure on the beach, flanked by a couple of carpenters living there. She threw her equipment into the skiff and we were off. Within minutes she picked out the Adak on the horizon.

Back on the tug the weather turned worse. We hobbyhorsed in and out of wave troughs, my bookcase toppling, a favorite mug crashing in the galley, exploding on the floor. I tried to wire running lights as spray came over the gunwales, but my hands were growing cold, fingers slowing. And then, after a desperate squeeze of the lineman pliers, the starboard light glowed green, the moon broke through the clouds, and the wind died down—as if the gods said, OK, enough.

We were sailing by moonlight over a streaky calm sea, a crosscurrent breeze threading through the open windows of the wheelhouse. Steve told tales, including one about a Norwegian tradition of fathers sinking boats, which they’d built for their sons, deep beneath the ocean to pressure-cure the wood. Years later their sons raised the boats, then repeated the process for their own sons. I nearly wept.

A splash off the bow. We gathered by the windlass, and Gavin shined his headlamp as Katie snapped photos of Dall’s porpoises, the white on their flanks and bellies reflecting back the light of the moon as they dodged the bow stem. We threaded into Portage Bay, working by that pale luminescence and instruments to find an anchorage. Just after 2 a.m. I went into the engine room to shut down the generator. There was an unfamiliar gushing, a rivulet somewhere in the bow. That chilling sound of water finding its way into the boat—nauseating.

Leroy, Steve, and I removed floor planks, shining light into the dark bilge. And there it was, a dime-size hole in a pipe allowing in an unhealthy dose of ocean. We repaired it with a section of blue hose, belt clamp, and epoxy. That night as we slept, it held.

Day Four

The following morning, about 20 miles north of Petersburg, our freshwater pump burned out. “Not built to work on,” Steve said, poking the shell of the beetle black plastic pump with a boot tip. The only material he hated more than iron was plastic.

This was my fault. Before leaving Sitka I had hesitated to fill up the forward tank with freshwater, afraid of going “ass over teakettle” as they say so charmingly in the industry. (The boat nearly did this one early morning in 2013.) What I didn’t understand was that the pump needed water from the forward tank not just for doing dishes, but also to fill jackets around the engine that serve as insulation. Without the water, the pump overheated. Without the pump, the engine wouldn’t cool.

One of the things I love about Steve, that I will always love, is that he skips blame. If you want to feel like a jackass (right then, I did) that was your problem. His time was spent on solutions—just so long as iron and plastic weren’t involved.

We fed our remaining drinking water into the tank. “Might be able to take in the skiff, fill up at a ‘crick,’” Steve suggested, considering the quarter inch on the sight gauge. “But don’t dillydally.”

What he meant was, you’re going to an island where bears outnumber humans, and meanwhile we’ll be pushing ahead for Petersburg until we run out of water. Don’t take your time.

Gavin, Katie, and I snapped on our life vests. I filled a backpack with flares, a sleeping bag, peanut butter and jelly, and a Glock 20. Xander released the skiff, and the tugboat receded from view. I studied the GPS, trying to locate said “crick.” When the water grew too shallow I raised the outboard, and we paddled the rest of the way to the beach, tossing the five-gallon jugs into the flattened tidal grass. Farther up the tideland, surrounded by bear tracks, we found a stream and filled the tanks. Gavin’s powerlifting strength was particularly welcome now as we hauled the jugs back to the skiff.

Aboard the Adak again, the three of us watched proudly as the level in the sight gauge rose. Gavin and I reboarded the skiff to go into Petersburg for a new pump. After tying up, I stopped by the harbor office to say we’d just be a minute.

“You guys coming in from a boat?”

“The Adak.”

Her eyes lit up. “I thought so. We’ve been waiting for you. Coast Guard’s got an all-boats alert.” I called the Coast Guard to tell them we were fine. There was no pump in town.

With 20 gallons of water for insurance—and a couple more of beer—Gavin slalomed us down Wrangell Narrows until we saw the blue exhaust of the Adak in the distance. We boarded, climbing to the wheelhouse as we worked our way through the passage.

And then, as we came around the corner—there they were. The lights of Wrangell.

And then the engine went dead.

This time, after four days at sea and as many breakdowns, no one panicked. We changed two filters, Steve blew through the fuel line to clear rust—spitting out a healthy mouthful of diesel—and we were moving again.

Through the darkness we picked out a green light that blinked every six seconds, and a red light that didn’t. Heritage Harbor. I lined up the bow stem with the lights. A harbor assistant flashed his truck lights to further guide us, and we eased the boat up to the rain-slicked dock. Resting a hand against the planking of the tug, I swear I could feel the boat exhale.

That night we cooked a dinner of venison burgers, sausage, and steak, all of us squished around the galley table, a film of sea salt and oil over our skin that cracked when we laughed—at how Gavin couldn’t stop eating candlefish, the oily smelt a friend gave us upon arrival; how Leroy lasted less than 24 hours as a cook because his preferred spice was cream of corn; how Steve liked to go hunting because the unexpected falls “knocked” the arthritis from his bones. Everything was hilarious that night.

A day behind schedule, and the Coast Guard alerted, but we had made it. When I called Rachel, she squealed. Tomorrow we’d know about the hull.

Day Five

The next morning, I discovered that the lift operator was not amused by our late arrival; we might have to wait up to four days to be pulled. Then, at quarter to noon, he grumbled that he had a window if we could make it over by 1 p.m.

We raced to our posts, powered up, and maneuvered the tug into the pullout. The Ascom hoist, big as a city building, motored toward us like some creature out of Star Wars. The machine groaned and the tug shifted in its straps. The harbormaster checked numbers on a control panel. “She’s heavy,” he said, “5,000 more pounds and we’re maxed out on the stern strap.” The lift exhaled and the boat dropped back down.

A crowd had gathered, watching the harbormaster, who looked down at the Adak, chin in one hand. This wasn’t happening, not after all we had been through. My mind raced. If the boat didn’t come up, our only other option was Port Townsend. That was a good 800 miles. Laughable.

Up the hull came. I held my breath. Back down. Oh God.

The fourth time, the propeller emerged from the water. I could make out the keel. Please keep coming. The lift stopped, the harbormaster checked the numbers and approached me, his face dour. Then he broke into a smile. “We’ll lift her.”

Streams of water poured off the keel stem as she rose, like a whale in the straps, hovering in the air, the bulk of her preposterous. “Three hundred and eleven tons,” he pronounced.

Eleven tons over capacity, but I didn’t ask questions.

That afternoon the thick grain of large-diameter Douglas fir emerged as we pressure-washed the bottom. I knew it before he said it, but how that tightness deep in my chest released when our shipwright, his head bent back as he looked up at the planks, shielding his eyes from the drips, said, “The bottom looks sweet.” The wood had been pickled, and stood up to the spray with no splintering. There was a rotten plank at the waterline, some gribble damage that would require replacing—but otherwise the boat was solid.

I called Rachel. “It’s gonna work. The boat’s okay.”

“Oh my God. I haven’t been able to sleep.”

*****

That first night in the boatyard I woke just after midnight and went outside in my slippers, fingering the gray canvas straps still holding us aloft. I thought of the weeks ahead, zipping off through-hulls, charring the planks, spinning oakum, using a beetle and horsing iron to re-cork. I thought about being alone in my hut in the woods, at the age of 19, with nothing to fear. And now, this boat, keeping me up into the early hours. My life had been braided into the Adak’s, just as it had been braided into Rachel’s life, and then Haley’s, and now someone else’s, ripening in Rachel’s belly.

Back in bed, the stateroom awash in the sodium yard lights, I thought of Xander and Steve, Gavin, Katie, Leroy, and Laddy, all the folks who had helped us get to Wrangell; the joy in their eyes when the boat emerged from the water; and back in Sitka, Rachel holding our child close, trusting so hard that this would work.

It was odd to be so still, floating here in the air, no rock of the hull from boats passing in the channel. And odd to finally understand after so long what the boat had been telling me all along: Trust me. I’m not going anywhere.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1607_Alaska_Contribs_02.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1607_Alaska_Contribs_04.jpg)