Alaska’s Great Wide Open

A land of silvery light and astonishing peaks, the country’s largest state perpetuates the belief that anything is possible

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Alaska-from-Denali-631.jpg)

We were flying what seemed only inches above a slope of the 20,300-foot-high Mount McKinley, now more often called by its Athabaskan name—Denali. Below our six-seat Cessna was a glacier extending 36 miles from the great peak. The doors of the little plane were open so that a photographer swathed in gloves and sweaters could lean out and capture the scene. I tried not to think about the statistic I'd spotted that morning on a bulletin board, a tally of the year's climbing figures at Denali: "Missing/Fatalities: 4."

It was a sparkling August morning—eight inches of snow had fallen four days before—and the snow line, after a chill and rainy summer, was already hundreds of feet lower than usual for this time of year. After barely six hours of sleep in semi-darkness, I had awoken at Camp Denali before dawn to see an unearthly pink glow light up the sharpened peaks. My cabin offered no electricity, no running water, no phone or Internet connection and no indoor plumbing. What it did offer was the rare luxury of silence, of stillness, of shockingly clear views of the snowcaps 20 miles away.

I'm not an outdoors person; the cabin's propane lamps defeated me daily and walking 50 feet through the cold near-dark to get icy water from a tiny tap was an amenity it took a while to appreciate. Northern exposure has never appealed to me as much as southern light.

But Alaska was celebrating its 50th anniversary—it became the 49th state on January 3, 1959—and the festivities were a reminder how, in its quirkiness, the state expanded and challenged our understanding of what our Union is all about. In almost 20,000 days on earth I had never set foot in our largest state, and as I stepped out of the Cessna and collected my heart again, wondering if forgoing travel insurance made me an honorary Alaskan, I was starting to see how Nature's creations could command one's senses as grippingly as any artist's perfections along Venice's Grand Canal. Wild open space holds a power that no museum or chandeliered restaurant can match.

Alaska plays havoc with your senses and turns everyday logic on its head. It's the westernmost state of the Union, as well, of course, as the northernmost, but I was surprised to learn, the day I arrived, that it is also (because the Aleutians cross the 180th meridian and extend to the east longitude side) the easternmost. Alaska is more than twice the size of Texas, I had read, yet has fewer miles of highway than Vermont.

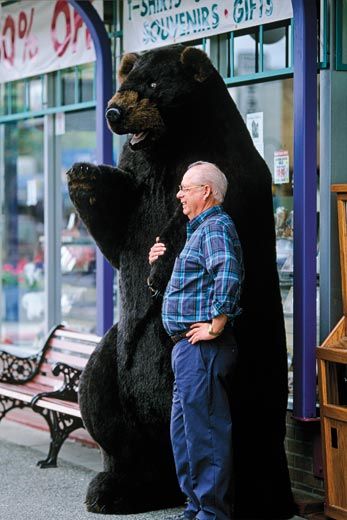

When faced with such facts, one reaches for bearings, for ways to steady oneself. Hours after I touched down, from California, I set my watch back an hour, walked the few small blocks of downtown Anchorage (ending abruptly at a great expanse of water) and realized I was surrounded by Canada, Russia and the Arctic. The unpeopledness and scale of things made me feel as if I had fallen off the edge of the earth, into an entirely otherworldly place like nothing I had ever seen (with the possible exception of Iceland or parts of Australia), with people sitting on benches in the weird gray light of 9:30 p.m. and indigenous souls selling turquoise-colored teddy bears along a busy street. The shops in the scrappy center of town were offering "FREE ULU KNIFE with purchase of $50 or more" and "Raven Lunatic Art." One store's signs—advertising salmon-leather wallets, Sahale nuts and sealskin tumblers—were in both English and Japanese. Large stuffed bears stood outside other stores, and a stuffed moose stood guard outside a Starbucks.

Yet all around these desultory and somehow provisional signs of human settlement there was a silver sharpness to the air, a northern clarity. On clear days, you could see Denali, 140 miles away, from downtown Anchorage. At midnight, you could read a book on an unlit street. I remembered that naturalist John Muir had found in the local skies a radiance and sense of possibility that seemed to border on the divine. "The clearest of Alaskan air is always appreciably substantial," the Scottish-born visionary had written—he had set off without his bride to scout Alaska days after his wedding—"so much so that it would seem as if one might test its quality by rubbing it between the thumb and finger."

You don't come to Alaska for its cities, I started to understand, but for everything that puts them in their place. An Anchorage resident pointed out a reindeer sitting placidly in a cage in a small downtown garden maintained by an eccentric citizen.

"Your first piece of wildlife!" my new friend announced with pride.

"Actually, my second," I countered. "I saw a moose grazing by the road just outside the airport, coming in."

"Yeah," he answered, unimpressed. "I saw some whales while driving up here. A bear, too. One of them just mauled a woman who was going for a hike in my neighborhood park. Right next to my house."

"In the outskirts of the city?"

"No. Pretty close to where we're standing right now."

The next day, the same matter-of-fact strangeness, the same sense of smallness amid the elements, the same polished wryness—and the way these played off scenes so majestic and overpowering they humbled me—resumed at dawn. A young newcomer from Virginia was driving our bus the five-and-a-half hours to the railway depot just outside Denali National Park. "You can look for some of the local sights as we pull out," he said as we started up. "One thing I like watching for is the gas prices rising as we go out of the city." A little later, taking on what I was coming to think of as a distinctive Alaskan love of drollness, he announced, "If you feel a strange fluttering in your heart, an inexplicable sense of excitement, that may be because we're coming up on the Duct Tape Capital of the World"—Sarah Palin's own Wasilla.

Yet as he dropped us at the park entrance, where a worn, dusty blue and white bus was waiting to take us into the wilderness itself, all ironies fell away. Almost no private cars are allowed in Denali—an expanse of six million acres, larger than all of New Hampshire—and the number of full-service lodges where you can spend the night can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Most people enter by bus, driving about 60 miles along a single narrow road to see what they can of "The Mountain," then hurry out again. We, however, were treated to a drive of 75 miles over unpaved roads to our little cabins in Camp Denali, where moose and bears walked around and towering snowcaps reflected in the pond.

When at last we drew up to our destination in the chill twilight, a troupe of caribou was silhouetted on a ridge nearby, and a golden eagle was diving down from its nest. By first light next morning, I felt so washed clean by the silence and the calm that I could hardly remember the person who, a week before, had run an apprehensive finger across a map from Icy Cape to Deadhorse to the first place I'd seen on arrival, Turnagain Bay—names suggesting that life was not easy here.

A quiet place, I was coming to see, teaches you attention; stillness makes you keen-eared as a bear, as alert to sounds in the brush as I had been, a few days before, in Venice, to key changes in Vivaldi. That first Denali morning one of the cheerful young naturalists at the privately owned camp took a group of us out into the tundra. "Six million acres with almost no trails," she exulted. She showed us how to "read" the skull of a caribou—its lost antler suggested it died before the spring—and handed me her binoculars, turned the wrong way round, so that I could see, as through a microscope, the difference between rushes and grass. She pointed out the sandhill cranes whose presence heralded the coming autumn, and she even identified the berries in bear scat, which she was ready to eat, she threatened, should our attention begin to flag.

The springy tundra ("like walking on a trampoline," a fellow visitor remarked) was turning scarlet and yellow, another augury of autumn. "You really don't need to calculate how many people there are per square mile," said a pathologist from Chattanooga squishing through the tussocks behind me. "You need to find out how many miles there are per square people." (He's right: the population density is roughly 1.1 person per square mile.)

What this sense of unending expanse—of loneliness and space and possibility—does to the soul is the story of America, which has always been a place for people lighting out for new territory and seeking new horizons. Every bus driver I met in Alaska seemed to double as tour guide and kept up a steady bombardment of statistics, as if unable to contain his fresh astonishment. Eleven percent of the world's earthquakes crack the ground here. There is a fault in Alaska almost twice as large as California's San Andreas. Anchorage is within 9.5 hours by plane of 90 percent of the civilized world (and roughly five minutes by foot from the wild).

"You need around 2,000 feet of water to land a floatplane," one of these sharers of wonders told me my first day in the state. "You know how many bodies of water with at least that much space there are in Alaska?"

"A thousand."

"No."

"Ten thousand?"

"No. Three million." And with that he went back to driving his bus.

A few hours after I got out of the wobbly, swooping Cessna that had whooshed me out of Denali, I was getting into another tiny mechanical thing with wings to plunge down into the hidden cove of Redoubt Bay. I stepped out of the plane, with two others, at a small landing in a lake, slopes of Sitka spruce rising above us, and as I walked into a lounge (where an iPod was playing the Sofia National Opera), I noticed fresh paw marks on the cabin door.

"A dog?" I asked.

"Naw. A bear. Go to one of the three outhouses out there and you're liable to meet her."

I sat down for a cup of tea and asked one of the workers how far to the nearest road.

"You mean a road that takes you somewhere?" he answered, and thought for a long, long time. "Round about 60 miles," he said at last. "More or less."

This isn't unusual for Alaska, and many homesteaders live so far from transportation that they have to flag down an Alaska Railroad train when they want to go into town. (Some haul back refrigerators and couches in its carriages.) Small wonder that so many of the few souls who do set up shop here, so far from society, take pride in their eccentricities. "Met a guy down at the Salty Dawg in Homer," one of the workers at Redoubt Bay began, "told me he could make me a nuclear bomb, right there at the bar. I thought he was putting one over on me, but a physicist friend said all the numbers checked out."

"Biggest number of bears I ever saw in this guy's backyard," another worker piped up, "was 52. He used to go round with a stick and put a roll of toilet paper on one end. Doused in kerosene and then lit. Shake that thing, the bears stayed away.

"Only time he killed a bear in 40 years was when one came into his house."

I've lived in the American West for more than four decades, but I began to wonder if I had ever really seen—or breathed—true American promise before. Every time I stepped off a boat or plane in Alaska, I felt as if I were walking back into the 19th century, where anything was possible and the continent was a new world, waiting to be explored. "Last time I was here, back in 1986," a Denali dinner-mate told me, "some folks from the lodge decided to go off panning for gold one evening. Over near Kantishna. One of them came back with a nugget that weighed a pound."

Once the season ended at Camp Denali, in mid-September, many of the young workers would be heading off to Ladakh or Tasmania or Turkey or some other faraway location. More surprisingly, many of the lodge workers and bush pilots I met, even those no longer young, told me that they migrated every winter to Hawaii, not unlike the humpback whales. Avoiding the lower 48, they crafted lives that alternated between tropical winters and summer evenings of never-ending light.

It was as if everyone sought out the edges here, in a society that offers no center and nothing seemed abnormal but normality. In the blowy little settlement of Homer—my next stop—kids in knit caps were serving up "Spicy Indian Vegetable Soup" in a café, dreadlocks swinging, while across town, at the famous Salty Dawg Saloon, weathered workers were playing Playboy video games.

Some of the shops nearby were selling qiviut scarves, made from the unimaginably soft fur of a musk ox, while others sold photographs of the unearthly wash of green and purple lights from the aurora in winter. Out on the Homer Spit someone had spelled out a message in twigs that seemed to speak for many: "I am Driftin'."

Roughly three out of every five visitors to Alaska view the state from their porthole as they sail along the coast. Many visiting cruise ships embark from Vancouver and head up through the Inside Passage to the great turquoise-and-aqua tidewater sculptures of Glacier Bay, the silence shattered by the gunfire sounds of chunks of ice ten stories high calving in the distance. For days on the ship I boarded, the regal Island Princess, all I could see was openness and horizon. Then we would land at one of the wind-swept settlements along the coast—Skagway, Juneau, Ketchikan.

In these rough, weather-beaten towns sustained by vessels that visit only a few months every year, you can sense the speculative spirit the state still inspires, translated now into a thousand tongues and a global hope. In Skagway, amid the old gold rush brothels and saloons, I came upon two doleful Turks selling lavish carpets at a store called Oriental Rugs. At the Port of Call shop around the corner, haunted mostly by crews from the cruise ships, a Romanian was chatting on a cellphone rented by the minute, while stewards and chambermaids browsed among piles of papadums and banana nuts. Next door, a man on a Webcam had awakened his wife back home in Mexico.

Alaska's state motto is "North to the Future," though of course the future never arrives. I walked around Juneau on a foggy, chill, late-summer morning (Southeastern Alaska's towns see an average of half an inch of rain a day), and the first statue that greeted me commemorated the 19th-century Philippine hero José Rizal, the poet and nationalist who was the most famous martyr of the Philippine Revolution, presiding over what is called Manila Square. Downtown I found a tanning salon, a Nepali handicrafts shop and a large emporium advertising "Ukrainian Eggs, Matreshka Dolls, Baltic Amber." Juneau, the only state capital that cannot be reached by road—"only by plane, boat or birth canal," a resident told me, in what sounded like a well-worn witticism—is nonetheless the home to fortune seekers from around the world drawn by its sense of wide-openness. Not far from downtown lies the Juneau Icefield, larger than Rhode Island and the source for the now receding Mendenhall Glacier, and in open waters half an hour away I saw humpback whales spouting and fanning their tails only a few feet from our boat, while sea lions cavorted even closer.

Alaska's central question is the American one: How much can a person live in the wild, and what is the cost of such a life, to the person and to the wild? By the time I reached Alaska, much of the world knew the story—dramatized by Jon Krakauer's book and Sean Penn's film, both called Into the Wild—of Christopher McCandless, the high-minded, unworldly dreamer who hitched his way to Alaska to live according to the back-to-the-land ideals of Thoreau and Tolstoy. Camping out in a bus near Denali, the idealist soon died. And every time a bear clambered across my horizon, I thought of Timothy Treadwell, another American Romantic archetype, who had spent summers in Alaska living with grizzlies, giving them names and convincing himself they were his friends, until an encounter with one went bad and he paid the ultimate price.

"A lot of people up here have no patience for these guys," a naturalist at Denali had told me when I asked her about the two men. "Because there are people here who have stayed in that bus, and they had no problems. But you've got to have respect for the land, to learn it. The one thing you learn here is preparedness."

That's why people in Alaska study how to read wolf scat and the habits of bears. "Right here she knows you're not going to come any closer, and she's fine," a guide at Redoubt Bay had explained about a nearby mother bear with her cubs. "But go somewhere she doesn't expect you, and Bailey will most likely kill you."

One morning in Denali, a hiking guide had pointed out a poisonous plant McCandless might have eaten by mistake. Then she showed me another plant, one, she said, that "would have kept him going to this day: Eskimo potatoes." (McCandless may have actually eaten the correct plant but mold on the seeds could have prevented his body from absorbing any nutrients.) To my eye they looked the same. I thought back to the maps I'd run my fingers along before coming here, many of the names opaque to me, others—Point Hope—sounding as if anxious visitors had tried, through invocation, to transform desolation into civilization. Some places seemed to combine prayers and warnings: Holy Cross, Elfin Cove, Cold Bay; Troublesome Creek, Moses Point, False Pass. Hours after I'd arrived in Anchorage, volcanic ash had drifted over from one of the Aleutian Islands, about a thousand miles away, closing down the airport—as if to say that all certainties were slamming shut and I was alone now in the realm of the possible.

Pico Iyer has written nine books. His most recent is The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama.

Editor's Note: A sentence in this article was corrected to clarify the geographic location of Alaska's easternmost Aleutian islands.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.