The Man Who Changed Reading Forever

The Venetian roots of revolutionary modern book printer Aldus Manutius shaped books as we know them today

:focal(520x214:521x215)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/6a/596a34db-8feb-40fc-87a8-48cbae59231e/sqj_1510_venice_aldus_03-web-resize.jpg)

Among the narrow cobbled sidewalks and winding canals of Venice’s Sant’Agostin neighborhood is a pretty yellow palazzo, its balcony overflowing with pink astoria flowers. Amid the ornate windows and lush flower boxes, it’s easy to miss a small plaque, carved in stone and written in formal Italian, commemorating one of the most important men in publishing history. This was the home of Aldus Manutius, says the plaque, and it was from here that “the light of Greek letters returned to shine upon civilized peoples.”

The palazzo, now divided into rental apartments and gift shops, is where Aldus forever changed printing more than half a millennium ago. He introduced curved italic type, which replaced the cumbersome square Gothic print used at the time, and helped standardize punctuation, defining the rules of use for the comma and semicolon. He also was the first to print small, secular books that could be carried around for study and pleasure—the precursors to paperbacks and e-readers today. “He was very much like the Steve Jobs of his era,” says Sandro Berra, managing director of the Tipoteca Italiana museum of typography outside of Venice (open to the public Tuesday to Friday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. and 2 p.m. to 6 p.m.; Saturday 2 p.m. to 6 p.m.). “He was ahead of his time, risking everything on an untested whim that somehow he knew would work.”

Fueling his risk-taking were fervent views on spreading knowledge to a broader audience. Before Aldus, books were extremely precious items, held in private collections or monasteries, inaccessible even to many scholars. “What he wrought, from the appearance of his first published book in 1493 until his death in 1515, was something akin to the first editorial boom,” writes Helen Barolini in her biography Aldus and His Dream Book. “He made the book an accessible vehicle of thought and communication.” Books, Aldus believed, provide an antidote to barbarous times and should not be hoarded by the privileged few. “I do hope that, if there should be people of such spirit that they are against the sharing of literature as a common good, they may either burst of envy, become worn out in wretchedness, or hang themselves,” he wrote in the preface of one of his volumes.

Aldus challenged received doctrine and sometimes pressed the limits of what the powerful Roman Catholic Church would accept. “He was the type who knew the difference between fearing God and fearing the church, and he lived his life on that fine line,” Berra says. “He also knew when to take a step back and reflect on what was important to his goals.” He printed most of the Greek canon for the first time and made secular literature portable, but he also printed important letters of the early church fathers; in 1518, his heirs printed the first edition of the Greek Bible.

**********

The 500-year anniversary of his death is being celebrated in New York and Venice and other cities where books are cherished. Early this year, he was honored with a far-reaching exhibition called “Aldus Manutius: A Legacy More Lasting Than Bronze” at the Grolier Club in Manhattan, where 150 of his antique volumes were on display. A series of memorial initiatives in Italy, where he is known as Aldo Manuzio, include a full calendar of “Manuzio 500” events in Venice, featuring readings and exhibits of his libelli portatiles (Latin for “portable books”), as well as demonstrations of the printing techniques he introduced.

Aldus was a complicated man. His legacy is anchored in Venice, but he was born in a village south of Rome. He came of age shortly after the final demise of the Eastern Roman Empire, which had long been in decline but fully collapsed after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453. He was a humanist, one of a small but growing number of scholars who studied ancient Greek and Latin texts at a time when most had all but given up on the classics, and a pioneer in the wave of Renaissance thinkers who helped salvage and eventually spur a reawakening of the region’s intellectual class.

In 1490, at the age of 40—in what might have been a midlife crisis—he moved to Venice. The city then was a humming capital of commerce, open to outsiders with fresh ideas. It was also writhing with creative energy, as artists and intellectuals from elsewhere in Europe flocked to the canals for inspiration. Aldus opened his own publishing house, the Aldine Press. His first book, Constantine Lascaris’s Erotemata, was followed by more than 130 other titles, including works by both Aristotle and Theophrastus.

Much of what made Venice a cultural hub in the 15th century remains intact today, albeit often hidden and protected from outsiders. It is possible to find a bar or café along a lonely canal where modern Venetians meet to share readings and discuss everything from theology to ancient history. “Aldus’s Venice is still here,” says Berra. “But the Venetians keep it to themselves, far away from the tourists.” Yet the purple sunsets and elegant palazzi along the Grand Canal haven’t changed much since Aldus’s time, and those remain open to all.

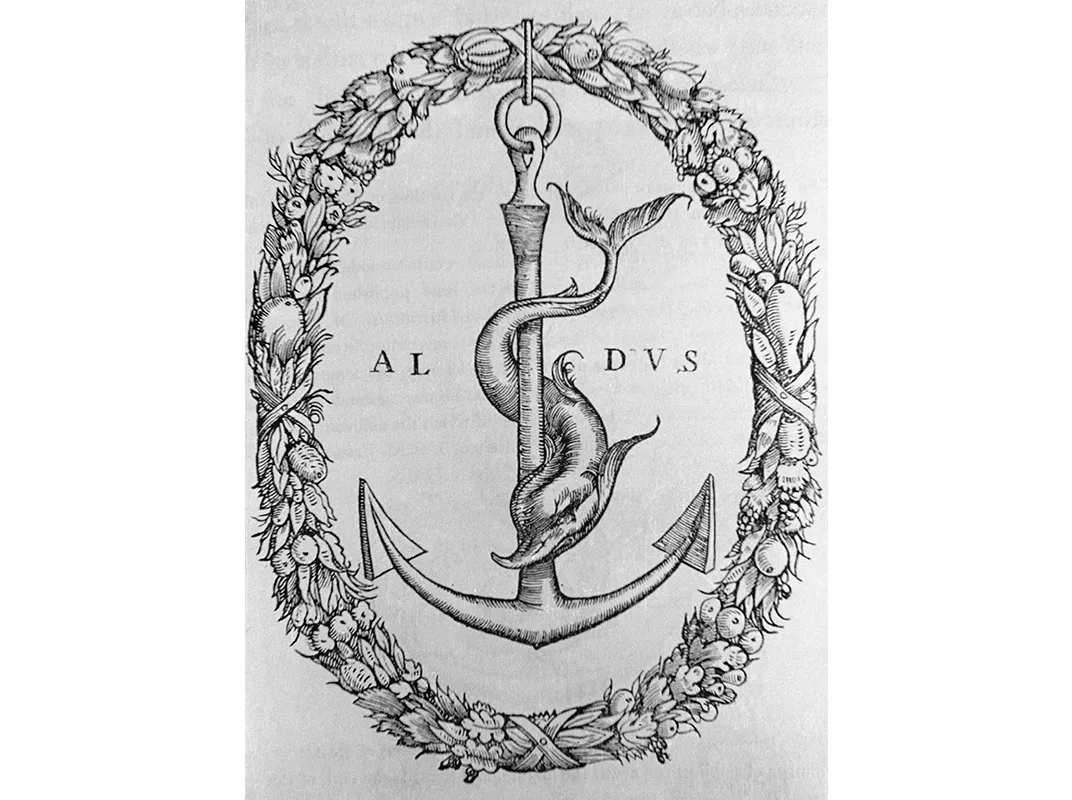

The techniques Aldus introduced were quickly copied across Italy, and later more broadly around Europe, with little credit given to the original printer. In 1502, when he printed Dante’s Divine Comedy, he introduced to the Aldine Press the emblem of a dolphin wrapped around an anchor, inspired by the Latin motto festina lente, or “hasten slowly.” The emblem is still used by Doubleday Books. Aldus’s name, meanwhile, has become associated with desktop publishing: The software company that introduced the innovative PageMaker program in 1985 is the Aldus Corporation, named in his honor.

Berra laments the fact that Aldus is appreciated more outside of Italy than he is at home. In recent years, he has been the subject of two novels: The Rule of Four, by Ian Caldwell and Dustin Thomason, published in 2004, and Robin Sloan’s 2012 best seller Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore. The Rule of Four is a page-turner in the style of The Da Vinci Code, focused on the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, an elaborately designed book that was controversial for its phallic illustrations; the Sloan novel features a secret society of bibliophiles and code-breakers that, as imagined by the author, originated with Aldus.

In Italy today, his name has more mundane associations. “If you ask people who he was, they might recognize his name as [that] of a street or their favorite restaurant or bar,” says Berra, but they wouldn’t be able to tell you much more. “That’s because historically typography is mistakenly considered a technique, not an art, but in reality it is as much an art as many other Italian treasures.” In Aldus’s time, it also had a profound purpose: to promote reading as a more common pursuit, and to spread knowledge as widely as possible.

Read more from the Venice Issue of the Smithsonian Journeys Travel Quarterly.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.