An Image of Innocence Abroad

Neither photographer Ruth Orkin nor her subject Jinx Allen realized the stir the collaboration would make

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Indelible-Jinx-Allen-631.jpg)

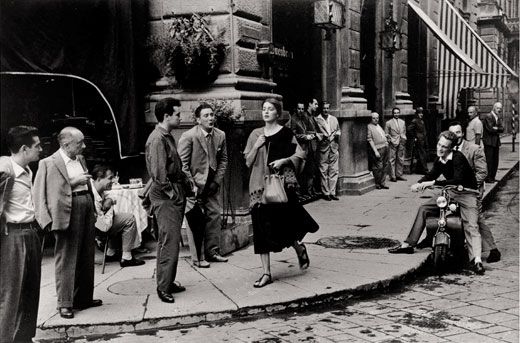

After spending a madcap day in Florence 60 years ago, Ruth Orkin, an American photographer, jotted in her diary: “Shot Jinx in morn in color—at Arno & Piazza Signoria, then got idea for pic story. Satire on Am. girl alone in Europe.” That’s all it was supposed to be.

“It was a lark,” says the woman at the center of Orkin’s picture story. Nonetheless, one of the images they made together, American Girl in Italy, would become an enduring emblem of post-World War II femininity—and male chauvinism.

The American girl, Ninalee Craig, was 23 years old and, she says, a “rather commanding” six feet tall when she caught Orkin’s eye at the Hotel Berchielli, beside the Arno, August 21, 1951. A recent graduate of Sarah Lawrence College in Yonkers, New York, she was then known as Jinx (a childhood nickname) Allen, and she had gone to Italy to study art and be “carefree.” Orkin, the daughter of silent-film actress Mary Ruby and model-boat manufacturer Sam Orkin, was adventurous by nature; at age 17, she had ridden a bicycle and hitchhiked from her Los Angeles home to New York City. In 1951, she was a successful 30-year-old freelance photographer; after a two-month working journey to Israel, she’d gone to Italy.

Before she died of cancer in 1985, at age 63, Orkin told an interviewer she had been thinking of doing a photo story based on her experiences as a woman traveling alone even before she arrived in Florence. In Allen, she found the perfect subject—“luminescent and, unlike me, very tall,” as she put it. The next morning, the pair meandered from the Arno, where Orkin shot Allen sketching, to the Piazza della Repubblica. Orkin carried her Contax camera; Allen wore a long skirt—the so-called New Look introduced by Christian Dior in 1947 was in full swing—with an orange Mexican rebozo over her shoulder, and she carried a horse’s feed bag as a purse. As she walked into the piazza, the men there took animated notice.

When Orkin saw their reaction, she snapped a picture. Then she asked Allen to retrace her steps and clicked again.

The second piazza shot and several others were published for the first time in the September 1952 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine, as part of a story offering travel tips to young women. Although the piazza image appeared in photography anthologies over the next decade, for the most part it remained unknown. Orkin married filmmaker Morris Engel in November 1952 and expanded her career to include filmmaking. Jinx Allen spent a few years as a copywriter at the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency in New York, married a Venetian count and, after their divorce, married Robert Ross Craig, a Canadian steel industry executive, and moved to Toronto. Widowed in 1996, today she has four stepchildren, ten grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

A quarter-century after it was taken, Orkin’s image was printed as a poster and discovered by college students, who decorated countless dorm-room walls with it. After years lying dormant, an icon was born. In its rebirth, however, the photograph was transformed by the social politics of a post-“Mad Men” world. What Orkin and Allen had conceived as an ode to fun and female adventure was seen as evidence of the powerlessness of women in a male-dominated world. In 1999, for example, the Washington Post’s photography critic, Henry Allen, described the American girl as enduring “the leers and whistles of a street full of men.”

That interpretation bewilders the subject herself. “At no time was I unhappy or harassed in Europe,” says Craig. Her expression in the photo is not one of distress, she says; rather, she was imagining herself as the noble, admired Beatrice from Dante’s Divine Comedy. To this day she keeps a “tacky” postcard she bought in Italy that year—a Henry Holiday painting depicting Beatrice walking along the Arno—that reminds her “of how happy I was.”

Within photography circles, Orkin’s famous image also became a focal point for decades of discussion over the medium’s sometimes troubling relationship with truth. Was the event she captured “real”? Or was it a piece of theater staged by the photographer? (In some accounts, Orkin asked the man on the Lambretta to tell the others not to look into her camera.) The answer given by historians and critics is usually hazy, perhaps necessarily so: They have spoken of “gradations of truth” and Orkin’s career-long search for “emotional reality.” But photographs, deservedly or not, carry the promise of literal truth for most viewers; disappointment follows the discovery that beloved pictures, such as Robert Doisneau’s Kiss by the Hotel de Ville, were in any way set up.

Does it matter? Not to Ninalee Craig. “The men were not arranged or told how to look,” she says. “That is how they were in August 1951.”

David Schonauer, former editor in chief of American Photo, has written for several magazines.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.