Ancient Citadel

At least 1,200 years old, New Mexico’s Acoma Pueblo remains a touchstone for a resilient indigenous culture

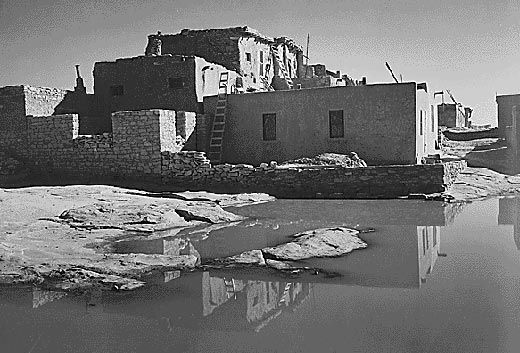

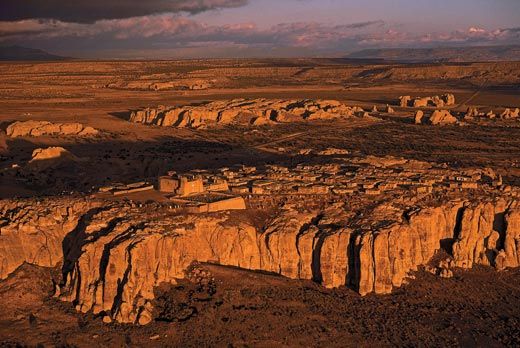

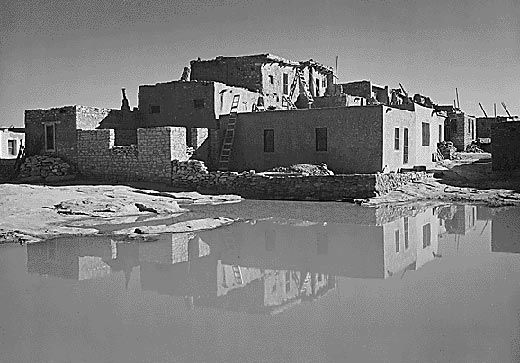

Peering up from the base of a sandstone mesa rising from the plains of central New Mexico, it's possible to make out clusters of tawny adobe dwellings perched at the top. The 365-foot-high outcropping, about 60 miles west of Albuquerque, is home to the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in North America—an isolated, easily defensible redoubt that for at least 1,200 years has sheltered the Acoma, an ancient people. The tribe likely first took refuge here to escape the predations of the region's nomadic, warlike Navajos and Apaches. Today, some 300 two- and three-story adobe structures, their exterior ladders providing access to upper levels, house the pueblo's residents.

Although only 20 or so individuals live permanently on the mesa, its population swells each weekend, as members of extended families (and day-tripping tourists, some 55,000 annually) converge on the tranquil site. (The pueblo has no electricity, although an occasional inhabitant has been known to jury-rig a battery to power a television.)

Today, the tribe numbers an estimated 6,000 members, some living elsewhere on the 600-square-mile reservation surrounding the pueblo, others out of state. But every Acoma, through family or clan affiliation, is related to at least one pueblo household. And if most tribe members have moved away, the mesa remains their spiritual home. "Acoma has always been the place where people go back," says Conroy Chino, the former secretary of labor for New Mexico, who is a partner in the Albuquerque-based NATV Group, a consulting firm specializing in American Indian issues. He returns to the mesa weekly for Acoma religious ceremonies. The tribe's "whole worldview," he adds, "comes from that place. It is the heart-center."

Acoma's history is etched in the walls of its adobe buildings. A row of houses near the mesa's north end still bears the scars of cannon fire, a reminder of the fateful day in 1598 when the settlement first fell to an enemy. Before then, the pueblo had interacted peaceably with Spanish explorers heading north from Central America. Members of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado's expedition first described the settlement in 1540, characterizing it as "one of the strongest places we have seen," a city built upon a rock so high "that we repented having gone up to the place." The only access then was by nearly vertical stairs cut into sheer rock face; today, one ascends by a narrow, vertiginous road blasted into the mesa during the 1950s.

Within a half century or so, however, relations with the Spaniards had deteriorated. In December 1598, the Acoma learned that one of the conquistadors, Juan de Oñate, intended to colonize the region. They ambushed Oñate's nephew and a party of his men, killing 11 of them. Brutal revenge followed: the Spanish burned much of the village, killing more than 600 inhabitants and imprisoning another 500. Survivors were made to serve as slaves; men over age 25 were sentenced to the loss of their right foot. (Even today, most Acoma resent Oñate's status as the state's founder; in 1998, shortly after a statue was erected in his honor in the town of Alcalde, someone took a chain saw to the bronze figure's right foot.)

Despite the lingering animus toward the Spanish, the pueblo remains a place where distinct cultures have been accommodated. In the village's primary landmark, the 17th-century San Esteban del Rey Mission, a 6,000-square-foot adobe church perched on the east edge of the mesa, the altar is flanked by 60-foot-high pine-wood pillars embellished with hand-carved braiding in red and white; the intertwined strands symbolize the fusion of indigenous and Christian beliefs. Interior walls feature images that reflect traditional Acoma culture—rainbows and stalks of corn; near the altar hangs a buffalo-hide tapestry depicting events in the life of the saint. From 1629 to 1641, Fray Juan Ramirez oversaw construction of the church, ordering the Acoma to haul 20,000 tons of adobe, sandstone, straw and mud—materials used in its walls—to the mesa. The tribe also transported ponderosa-pine timber for roof supports from Mount Taylor, 40 miles away. Despite the use of forced labor in the church's construction, most of today's Acoma regard the structure as a cultural treasure. Last year, in part because of the church, which represents a rare mixing of pueblo and Spanish architecture, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named Acoma mesa as the 28th National Trust Historic Site, the only Native American site so designated.

Also last year, the Acoma inaugurated a new landmark, the Sky City Cultural Center and Haak'u Museum, at the foot of the mesa (the original was destroyed by a fire in 2000). "This place," says curator Damian Garcia, "is for the people." He adds that its primary purpose is "to sustain and preserve Acoma culture." Inside the center a film surveys Acoma history and a café serves tamales and fry bread. The architects drew on indigenous design conventions, widening doorways at the middle (the better, in traditional dwellings, for bringing supplies, including firewood, inside) and incorporating flecks of mica in windowpanes. (Some windows on the mesa are still made of it.) Fire-resistant concrete walls (a departure from traditional adobe) are painted in the ruddy pinks and purples of the surrounding landscape.

Acoma artwork is everywhere at the Center, including on the rooftop, where ceramic chimneys, crafted by a local artist, can be seen from the mesa. A current exhibition showcasing Acoma pottery celebrates a tradition that also dates back at least a millennium. According to Prudy Correa, a museum staffer and potter, the careful preparation of dense local clay, dug from a nearby site, is essential to Acoma artisanship. The clay is dried and strengthened by adding finely pulverized pottery shards before pots are shaped, painted and fired. Traditional motifs, including geometric patterns and stylized images of thunderbirds or rainbows, are applied with the sturdy spike of a yucca plant. "A regular paintbrush just doesn't work as well," she says. Correa recalls her grandmother, a master potter, picking up a finished pot, striking the side slightly and holding it to her ear. "If it didn't ring," Correa says, it indicated that the piece had cracked during firing. It would be discarded and "ground back down to shards." Today, Correa is teaching her 3-year-old granddaughter, Angelina, to craft Acoma pottery.

In September, the Acoma honor their patron saint, Esteban (or Stephen, a pious 11th-century Hungarian king). On the feast day, the mesa is open to anyone. (Ordinarily, it's necessary to reserve ahead to tour the pueblo; overnight stays are not permitted.) Last September, when I joined more than 2,000 fellow pilgrims gathered for the San Esteban festival, I hopped aboard a van that shuttled visitors from the base of the mesa to the summit. Ceremonies began in the church. There, a carved-pine effigy of the saint was taken down from the altar and paraded into the main plaza, to the accompaniment of chanting, rifle shots and the ringing of steeple bells. The procession wound past the cemetery and down narrow unpaved streets, where vendors offered everything from pottery to traditional cuisine—small apple pastries and foil-wrapped corn tamales.

At the plaza, bearers placed the figure of the saint in a shrine lined with woven blankets and flanked by two Acoma men standing guard. A tribal leader, Jason Johnson, welcomed all, speaking the first English I heard that day. The daylong dancing and feasting had begun.

Marvis Aragon Jr., CEO of the tribe's commercial ventures (including its casino), was wearing tribal dress. He danced under the hot sun with scores of Acoma—men and women, young and old. At her home, Correa was serving traditional dishes to friends and family members: green-chili stew with lamb, fresh corn and wheat pudding with brown sugar. Another Acoma artisan, Bellamino (who regards his family's Spanish surname as a symbol of subjugation), sold pottery, silver jewelry and baskets from the front room of his adobe. Later in the day, David Vallo, leader of the tribal council, surveyed the crowds from the edge of the central plaza. "This," he said, "is the time my people come back."

Across the centuries, the mesa—a citadel fortified against threat—has represented Acoma endurance. The sheer sandstone walls have also cast a spell on virtually any traveler who has ventured this way. "I cannot but think that mother nature was in a frenzy when she created this spot," wrote one 19th-century visitor. And Charles Lummis, a journalist who arrived there in 1892, called the site "so unearthly beautiful, so weird, so unique, that it is hard for the onlooker to believe himself in America, or upon this dull planet at all."

Author David Zax is a writing fellow at Moment magazine in Washington, D.C.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)