Antarctica Erupts!

A trip to Mount Erebus yields a rare, close-up look at one of the world’s weirdest geological marvels

George Steinmetz was drawn to Mount Erebus, in Antarctica, by the ice. The volcano constantly sputters hot gas and lava, sculpting surreal caves and towers that the photographer had read about and was eager to see. And though he'd heard that reaching the 12,500-foot summit would be an ordeal, he wasn't prepared for the scorching lava bombs that Erebus hurled at him.

Steinmetz, 49, specializes in photographing remote or harsh places. You're almost as likely to find him in the Sahara as at his home in Glen Ridge, New Jersey. Thanks to his expedition to Erebus last year, funded by the National Science Foundation, he's one of the few photojournalists to document up close one of the world's least-seen geological marvels. Most of his photographs were taken during the soft twilight that passes for night during the polar summer.

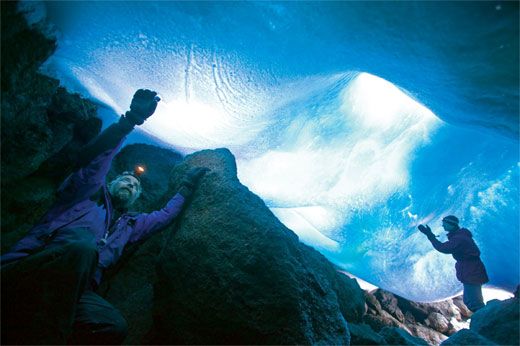

The flanks of Erebus are spiked with ice towers, hundreds of them, called fumaroles. Gas and heat seeping through the side of the volcano melt the snowpack above, carving out a cave. Steam escaping from the cave freezes as soon as it hits the air, building chimneys as high as 60 feet.

The scientists who work on Mount Erebus say that its ice caves are every bit as much fun to explore as you might expect. But the scientists are more interested in the volcano's crater, with its great pool of lava—one of the few of its kind. Most volcanoes have a deep central chamber of molten rock, but it's typically capped by cooled, solid rock that makes the hot magma inaccessible. On Mount Erebus, the churning magma is exposed at the top of the volcano, in a roiling 1,700-degree Fahrenheit lake perhaps miles deep. "The lava lake gives us a window into the guts of the volcano," says Philip Kyle, a volcanologist at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology.

Mount Erebus looms over the United States' main research base in Antarctica, McMurdo Station, on Ross Island. Most of the year scientists monitor the volcano remotely, gathering data from seismometers, tilt meters, GPS signals, video cameras and microphones. They helicopter the 20 miles from McMurdo to Erebus at the beginning of the six-week field season, which lasts from mid-November to early January, when the temperature on the mountain can reach a balmy -5 degrees. Still, winds can whip at 100 miles per hour, and blizzards and whiteouts are common. The researchers often get stuck in their research camp—two 16- by 24-foot huts at 11,400 feet elevation—waiting for the weather to clear. Out of the eight days that Steinmetz spent on the volcano, he was able to work for only two.

On their first clear day, Steinmetz and Bill McIntosh, also of New Mexico Tech, rode snowmobiles up to the crater's rim. As they headed back down, Mount Erebus spattered lava over the area they'd just explored. "It looked like shotgun blasts," says Steinmetz. "There were puffs of hot steam where the lava bombs hit." Kyle, who has been monitoring the volcano for more than 30 years, says it had recently broken a two-year quiet spell. Mount Erebus had started acting up in early 2005, and when scientists arrived it was erupting several times a day, each time ejecting 50 or so lava bombs. The largest are about ten feet wide—great blobs of bubbly lava that collapse like failed soufflés when they land, some almost a mile away.

Erebus and the rest of the continent will come under more scrutiny than usual in 2007, as scientists head to the ends of the earth for the fourth International Polar Year since 1882. They'll try out new monitoring techniques, study how Antarctica and the Arctic influence worldwide weather, and probe what kind of life could exist in the extreme cold and winter-long dark of the poles.

Mount Erebus' ice caves are among the most promising places for undiscovered life in Antarctica. Though they grow or shrink depending on how much heat the volcano emits, inside they maintain a temperature of about 32 degrees. Says McIntosh: "The caves are wonderful because they're so warm."

George Steinmetz's photographs of Peruvian pyramids and Mexican cave paintings have appeared in Smithsonian. Senior editor Laura Helmuth specializes in science.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)