Archaeology and Relaxation in Santorini

The Greek isle, a remnant of a long ago volcanic eruption, has most everything a traveler would want: great food and awe-inspiring scenery

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Life-List-Santorini-631.jpg)

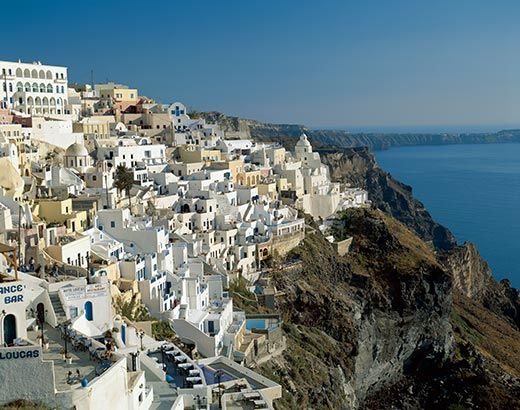

Some time ago, I gazed out from a balcony, peering over potted geraniums to the azure Aegean; it seemed, from my aerie, that I was perched at the edge of the world. And so I was, on edenic Santorini, the southernmost isle of the Cyclades. Its dramatic geography is unique, even in this corner of the classical world, where landscapes of rugged beauty rise up for travelers at every turn. Santorini’s villages cling to red-and-black cliffs, looking out on a nearly enclosed 400-foot-deep lagoon; this deep harbor was formed when a catastrophic volcanic eruption occurred some 3,600 years, creating a massive crater. Lawrence Durrell, the 20th-century expatriate British novelist who spent his childhood on the island of Corfu, once wrote that “It is hardly a matter of surprise that few, if any, good descriptions of Santorini have been written: the reality is so astonishing that prose and poetry, however winged, will forever be forced to limp behind.”

I happened to have a copy of Durrell’s The Greek Islands at my side as I took in the vista of sea and sky on that serene evening, anticipating one of the sunsets for which this island is renowned. The meal was ambrosial as well. A friendly taverna owner served swordfish drizzled in sage-infused olive oil; a plate of perfect cherry tomatoes (the island is famous for its tomatoes); a ripe peach sliced and garnished with fresh mint; a slice of walnut pie and a dollop of Greek yogurt with honey. And let me not neglect to mention the wine: Santorini’s volcanic soils produce notable vintages, whites especially, dry, citrusy and delectable. The vineyard owners are welcoming and knowledgeable; later in our stay here, we would spend a day bumping along dusty roads in our rented Jeep, strolling rows of grapes and tasting the offerings.

The beaches, many of them black volcanic sand (which absorbs heat: bring thick towels to stretch out on and do not leave home without sandals) are unspoiled and beckoning; the Aegean is warm and impossibly blue. Tempting as the beaches were—one could easily return there daily for the seaside holiday of one’s dreams— I found that I wanted even more to while away the hours in the narrow streets of our picture-postcard village, Oia. Its residents long ago imposed draconian zoning restrictions; their wisdom is a boon to visitors, who will discover, even today, intact whitewashed architecture; grand 19th-century merchants’ villas; churches roofed in cobalt-blue domes; galleries; small shops where one may search out hand-embroidered tunics or silver bracelets embellished with leaping dolphins; lavender sachets or packets of herbal teas—tisanes—dried and tied in muslin by local farmers.

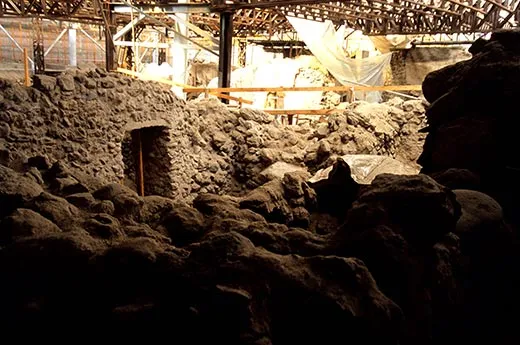

Santorini is also home to one of the most significant excavation sites in the Mediterranean, Akrotiri, the ruins of an ancient town, well preserved because, like Pompeii, it was buried in a volcanic eruption. (Archaeologists believe, however, that the inhabitants escaped; there has been no evidence uncovered that residents were trapped there.) The nearby Museum of Ancient Thera showcases the artifacts unearthed there; one can easily spend an entire day peering at artifacts, including pottery and jewelry, that vividly evoke the world of a Minoan Bronze Age settlement.

Its essence, however, Santorini’s fundamental attraction is its profound aura of calm. In Oia’s clear air and quiet byways, church bells chime; black-garbed elderly women sit in doorways, shelling fava beans; and chickens cluck in the kitchen gardens. It seems that there are few places in the world where time stands still—but this is one of those rare refuges.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.