Since the University of California, San Diego closed its doors due to the pandemic, Mary Beebe has not been allowed to return to her offices. Instead, the director of the 1,200-acre Stuart Collection of public art on-site has been taking advantage of the open campus to walk her dog. Like many other locals in the seaside neighborhood of La Jolla, Beebe has tapped into the magic of open-air, art-studded parks.

With many galleries and museums closed, sculpture parks and gardens have emerged as alternative, socially-distanced public spaces punctuated with art. From New York to Minneapolis to San Diego, art institutions have kept these outdoor venues open, cementing the importance of an art movement that began in the 1960s.

In Seattle, the nine-acre Olympic Sculpture Park has remained open throughout the pandemic. Seattleites have been spotted having picnics near Alexander Calder's abstract red Eagle and walking their dogs around Richard Serra's majestic Wake. “The Olympic Sculpture Park is embedded into the daily life of the city," says Amada Cruz, director of the Seattle Art Museum, which operates the sculpture park. "With SAM’s other two sites closed in response to the pandemic, it’s become even more important as a beautiful outdoor space where people can safely experience both art and nature."

Throughout the country, sculpture parks have become outdoor living rooms. In Raleigh, North Carolina, the Ann and Jim Goodnight Museum Park, which sits on the 164-acre campus of the North Carolina Museum of Art, has even seen an uptick in visitors this summer. In April and May, nearly 100,000 visitors per month spent time on site, compared to the 150,000 in March, April and May combined last year. "During this time, while we are physically separated from much of our community, the Museum Park has remained a place for rest, recreation and contemplation," says Valerie Hillings, the museum’s director.

In Queens, New York, Socrates Sculpture Park's unique status as a public park designated for public recreational use, has also meant a great deal for the local community. Located in New York's most diverse borough, but also the hardest hit by COVID-19, Socrates Sculpture Park has just unveiled “Monuments Now,” a new exhibition that speaks to the role of monuments in society and seeks to honor marginalized communities. "At this difficult moment in history, the park is a vital oasis of art and nature for the people of the ‘World's Borough,’" says park director John Hatfield.

According to the International Directory of Sculpture Parks & Gardens, nearly 300 sculpture parks and gardens exist in the U.S. today. With one or more in almost every state, it's hard to find a major museum without some form of outdoor sculpture venue. The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston all come with varying types of sculpture gardens, from the art oasis built atop a parking lot in Chicago to the urban green space with lawns, tall grasses and wetlands in Minneapolis. But sculpture parks were not always as ubiquitous as they are today.

Founded in 1931, the Brookgreen Gardens in Murrells Inlet, South Carolina, is the country’s first public sculpture garden, exhibiting the largest collection of American figurative sculpture in the country. Eight years later, the New York City’s Museum of Modern Art pioneered the museum sculpture garden concept by building an outdoor gallery for changing exhibitions. Bringing nature, art and architecture together in a then-novel way, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden has become a fixture in midtown Manhattan.

"Sculpture in the modern era became much more ambitious in terms of the variety of materials, in terms of its scale, so sculpture outgrew most indoor spaces," says John Beardsley, an art historian and curator of the inaugural Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize. He has written numerous books on landscape architecture and served as the curator of the 1977 landmark exhibition, “Probing the Earth: Contemporary Land Projects,” at Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

David Smith, the American sculptor known for large, welded steel geometric sculptures like Hudson River Landscape and his Cubi series, was one of the first sculptors to exhibit his art outdoors. "They are conceived for bright light, preferably the sun," he wrote. At first, he kept his smaller works at home, but as the scale got bigger, he began to set his sculptures in the fields of Bolton Landing, New York, where he moved permanently in 1940.

To date, Storm King Art Center, the world-renowned, 500-acre outdoor museum located in New York's Hudson Valley, has one of the most significant institutional holdings of David Smith's works. Founded in 1960, Storm King as we know it was directly shaped by its cofounder Ralph E. Ogden's acquisition of 13 of Smith's sculptures in 1967. After visiting the artist's studio in Bolton Landing, Ogden shifted his collecting efforts to outdoor sculpture.

"In the wake of the ‘60s, a commitment emerged to bring sculpture to the public," says Beardsley. "So, instead of making people go to museums to see art, increasing numbers of artists and curators and administrators wanted to take art to the public." In 1969, the A. D. White Museum of Art (now the Johnson Museum of Art) at Cornell University presented “Earth Art,” the first American exhibition dedicated to outdoor art. Installed around campus and the surrounding Ithaca area, land artists such as Jan Dibbets, Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson—best known for his Spiral Jetty, a 1,500-foot-long coil on the northeastern shore of Utah’s Great Salt Lake—used the earth as a canvas, evading the traditional confines of indoor galleries.

"The sculptors got more interested in the dialogue between their work and landscape, so they started to engage with materials, with topography, with weather, with all sorts of natural features in the landscape," says Beardsley. "The environmental ambitions of sculpture starting in the ‘60s accelerated the interest in sculpture parks and gardens."

Around the same time, public art programs entered the picture. In 1963, the General Services Administration created their Art in Architecture Program in an effort to incorporate the art of living American artists into the design of federal buildings, like Alexander Calder’s Flamingo, unveiled in 1974 and perched on the plaza of the Chicago Federal Center. In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, the National Endowment for the Arts began their Art in Public Places Program, funding the creation of more than 700 works between 1967 and 1995. A lot of cities passed a Percent for Art Ordinance, requiring that one percent of the total dollar amount of any city-funded construction project be devoted to original site-specific public art. Established in 1959, Philadelphia's Percent for Art program was the first in the nation, funding over 600 works in the city.

On-campus sculpture parks are the epitome of democratic art. At UC San Diego, the Stuart Collection is open 24/7, 365 days a year—and not only to students. Today, it amounts to 18 site-specific works by leading artists. "You don't have to get into a museum or an art frame of mind, you just see them or hear them all the time, so they become part of your experience, whether you're thinking about art or not," says Beebe. "And I love the fact that they provide a whole different dimension to the campus. It's a little bit like a treasure hunt." Even now, with campus closed during the pandemic, Terry Allen's Trees still whisper poems, and Mark Bradford's What Hath God Wrought—a metal pole sculpture, mounted with a flashing light—still flashes. "It just feels alive," says Beebe.

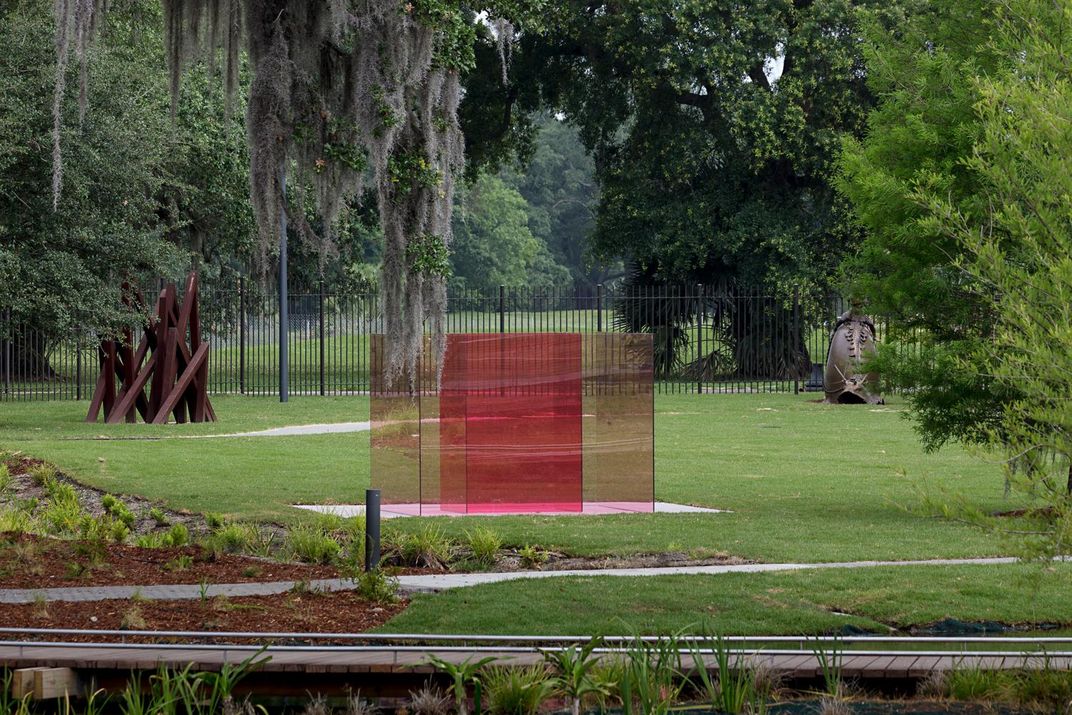

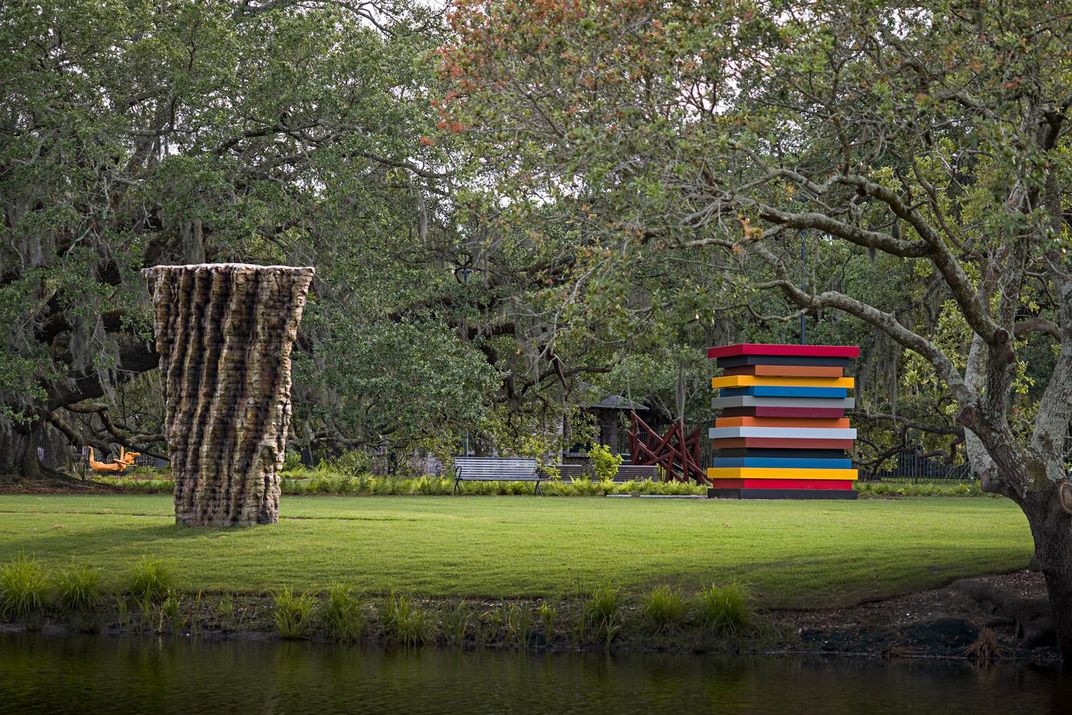

Like everyone and everything this summer, sculpture parks have been forced to adapt. At the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Sydney and Walda Besthoff Sculpture Garden reopened on June 1. The garden, which used to be free flowing, has adopted a one-way traffic system to facilitate social distancing, and all but one of the entrances have been closed, in order to adhere to city and state guidelines and keep track of visitor numbers.

Elsewhere, sculpture parks have taken advantage of their outdoor space to host a diverse roster of events. The Olympic Sculpture Park is offering its space as a venue for performing arts. Northeast of the Twin Cities, the Franconia Sculpture Park has been holding sculpture workshops and free film screenings throughout the summer. And in Richmond, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) is planning pop-up classes for August and early childhood education programs for September and October in their E. Claiborne and Lora Robins Sculpture Garden.

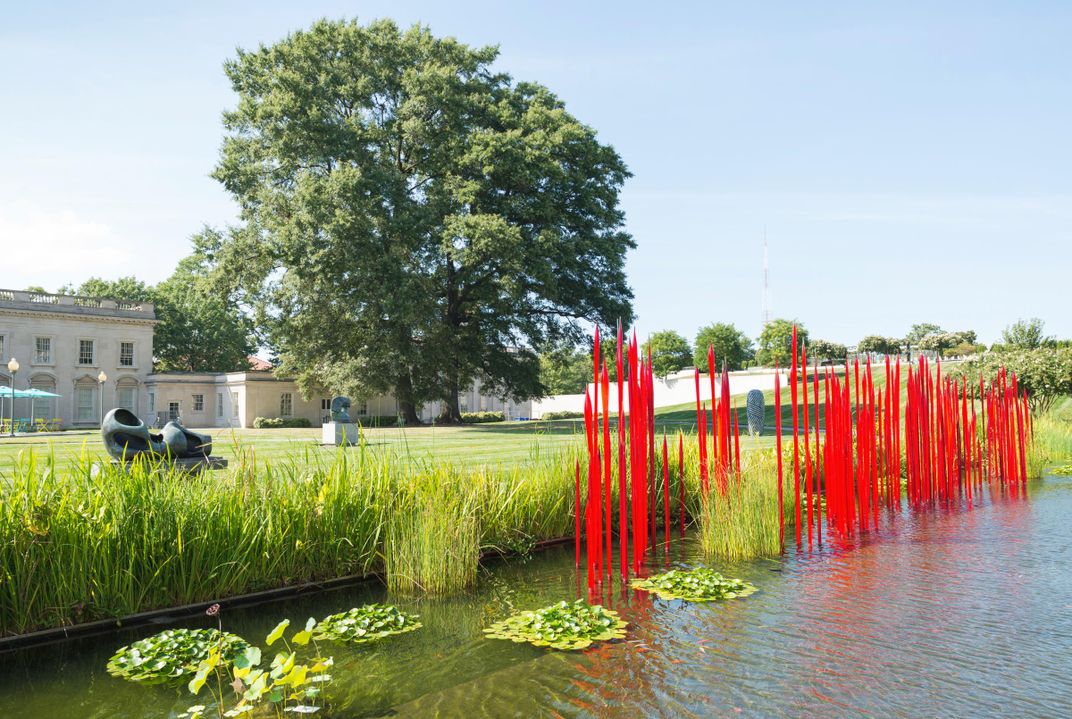

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’ garden, which reopened in 2011 to a new design by Rick Mather Architects, features the much-photographed Red Reeds, a Dale Chihuly installation made up of 100 glass rods that appear to be growing from the garden’s reflecting pool. "They are transformative if for nothing else because of their brilliant color, and it's a color that relates differently in each of the seasons," says Alex Nyerges, director of the VMFA. "In the fall, the Red Reeds echo the trees that populate the garden, and during spring and summer, they become yet another example of a flowering feature. That brilliant red just shines."

There is something particularly dynamic about outdoor art—a constant dialogue between form, material, changing seasons and changing light that augments the experience of parks. There is something physical, too. Unlike museums, some sculpture gardens encourage visitors to interact with the art, which is rarely cordoned off. At Storm King, the full realization of Momo Taro, by Japanese American artist and landscape architect Isama Noguchi, depends on the interaction of visitors, who are invited to touch, climb inside the hollowed out granite pit, sit and sing.

In a world with COVID-19, physical contact with the art is prohibited at Storm King, which reopened on July 15, as well as other sculpture parks. But being surrounded by art is empowering enough, particularly at a time when our interactions have been reduced to the click of a mouse zooming in and out of a virtual exhibit. Sculpture parks and gardens offer an alternative from the digital realm.

Fueled by a radically transformed art scene, outdoor art is having a moment. "The experience of art is going to need to be decentralized and dispersed, so there's going to be increased demand on the many different opportunities to experience art outdoors," says Beardsley, suspecting that large art institutions won't be able to accommodate crowds like they used to for some time. He adds, "It's going be a lot safer to experience art outdoors than indoors."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/41/e1418374-9609-4ef7-9428-c8528e044326/sculpture_parks-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0b/8b/0b8b04c7-8ab2-4e9a-b985-3e15cb4f5c96/sculpture_parks-social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Elissaveta_M._Brandon.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Elissaveta_M._Brandon.jpeg)