At the Pageant of the Masters, Famous Works of Art Come to Life

For nearly a century, a volunteer cast has recreated visual masterpieces on stage in Laguna Beach, California

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/79/e8/79e81708-5e6d-4324-b0c9-35bfce80e673/pom_breezingup_homer.jpg)

The large-scale pieces of art displayed on stage at the Pageant of the Masters, a nightly summer performance in Laguna Beach, California, look as though they could’ve been plucked off the walls of some of the world’s most celebrated museums and art galleries. On closer inspection though, it becomes evident that each masterpiece is an illusion. A blink of an eye or a subtle shift in posture and suddenly audience members are well aware that what they’re looking at is a collection of tableaux vivant, or “living pictures,” and the characters in each piece are real people.

This trick of the eye has been drawing crowds from across California and around the world for nearly a century. The Pageant of the Masters dates back to 1932, when local artist John H. Hinchman produced a summer festival for art enthusiasts who also happened to be in nearby Los Angeles for the Olympic Games. It proved so successful that the following year organizers added “living pictures” to the lineup, featuring real-life replicas of a number of famous works, including James McNeill Whistler’s 1871 oil painting titled Whistler’s Mother. The only difference is that an actress dressed in full costume, replete with a lace kerchief on top of her head, stood in for his mother, Anna McNeill Whistler.

The tradition of creating tableaux vivant dates back long before the pageant, with historians tracing it to medieval times. Living pictures evolved from Ancient Greek mythology and miming, and were common liturgical and ceremonial events at the end of a mass during that time. In Victorian England, these performances served as entertaining parlor games. The live recreations featured “figures posed, silent and immobile, for 20 or 30 seconds in imitation of well-known works of art,” according to The Chicago School of Media Theory. By the mid-1800s, the practice crossed the Atlantic to the United States, where it become a popular fad. More recently, in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles challenged people to recreate famous works using clothing and props they had on hand in quarantine.

Fast forward to today, and the pageant's 86th season is underway, as part of the Festival of Arts of Laguna Beach, an eight-week art extravaganza that includes a juried art show, guided art tours, workshops, live music and more. This year’s event is particularly special considering the 2020 pageant and festival were both canceled due to the Covid-19 pandemic. (The only other cancellation in its history was a four-year hiatus during World War II.) As with previous seasons, it's being held outdoors at a theater located on the Festival of Arts grounds. Certain Covid-19 precautions are being taken by the festival. The pageant, for example, has enhanced its cleaning and disinfecting protocols. Masks are optional if you've been vaccinated.

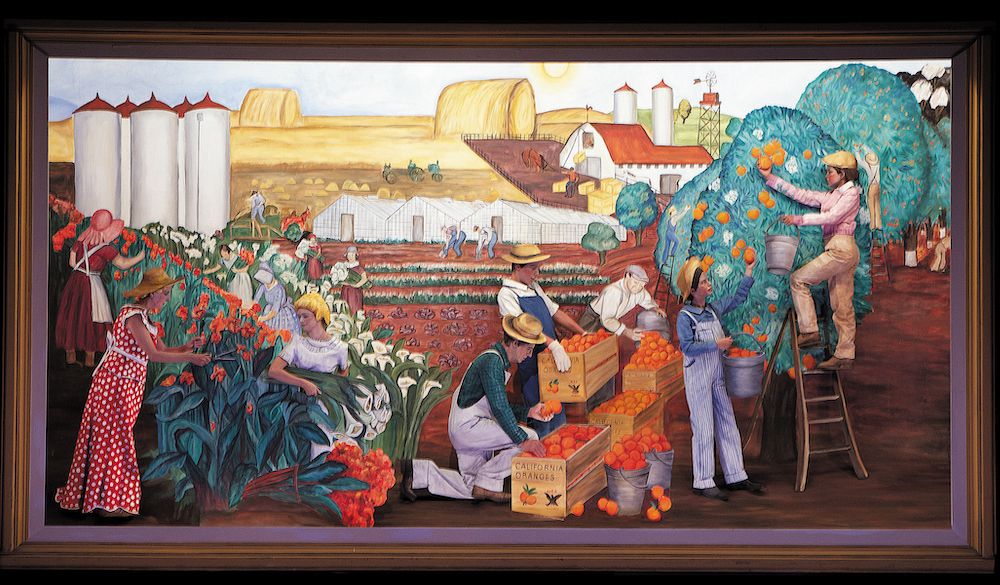

Each year the pageant takes on a different theme. In 2019, when the show last ran, the theme was “The Time Machine,” and the pageant toured through past, present and future artworks as well as important art events in history, such as the 1913 Armory Show, also known as the International Exhibition of Modern Art, in New York City. This year’s theme, “Made in America,” focuses on works created by American artists. In total, there are 40 different artworks performed on an outdoor stage, with each narrated segment lasting approximately 90 seconds in length before the stage crew seamlessly transitions to the next artwork while a live orchestra provides a musical backdrop.

(This video from 2018 shows how a “living picture” is pieced together.)

Some of the highlights from this year’s event include Nighthawks by Edward Hopper; The Passage of the Delaware by Thomas Sully; a trio of sculptures titled Hiawatha’s Marriage, Hagar and The Death of Cleopatra by Edmonia Lewis; and Lincoln Memorial by Daniel Chester French. However, there are a few exceptions to the all-American lineup, including the Statue of Liberty by French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and the show’s long-time finale, The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci.

As an attendee, I was able to go behind-the-scenes an hour or so before the show and saw several of the artworks up close on stage. But there was something obviously missing: the characters. While the execution of each landscape and scene was impressive, it wasn't until I was seated in the audience and saw the performers in their roles that each artwork truly came to life. There were times that I felt like I was at a museum viewing the original masterpieces and not in a theater surrounded by fellow art lovers.

The responsibility of choosing each year’s theme goes to Diane Challis Davy, who celebrates her 25th season as pageant director this year. (She made her pageant debut as a volunteer cast member when she was a teenager in 1976, appearing in The Tea Party by painter Mary Cassatt.) Working a year in advance, she chooses the theme, and then, with the help of fellow pageant staff members and volunteers, selects which artworks will be in the final lineup.

“Dan Duling, our scriptwriter, takes images of each potential artwork and pins them on a bulletin board to create a storyboard,” Challis Davy says. “We’ll haggle over which ones should be included. We don’t select anything that we can’t physically recreate or think we can’t do a decent job in reproducing. We used to have to visit libraries to do our research, but now everything is available on the internet and we have accessibility to vast art collections and can contact museums directly about gaining permission to do our recreations.”

Once the lineup is in place, a team of set designers helmed by technical director Richard Hill creates the sets, with each one replicating the artworks down to the slightest brushstrokes. Strategic lighting is used to transform each piece from three-dimensional to two-dimensional, eliminating any shadows that cast members might make during their 90-second performance. An oversized frame borders the scene. Costumery and makeup are also important to getting the illusion just right. Each costume is custom-made by a group of designers and volunteers using muslin, with every piece painted with a combination of acrylic and latex paint in the exact likeness of the original artwork. Volunteer makeup artists use both makeup and body paint to ensure that the cast members resemble the subjects of the art. Often digital projections and LED lighting are incorporated to add the final touches before the curtain goes up.

Cast members are also volunteers, and many of them have been coming back to perform year after year, including Michelle Pohl, who appeared in her first pageant in 1987 at the age of five. (Her role was in The Family Gathering, a Dresden porcelain piece, the artist unknown.) She volunteered as a cast member off and on until 2019; this year marks her first pageant as makeup director, leaning into her background as an artist. Although she's no longer in the cast, her husband, daughter and son are featured regularly.

“Each year, the pageant brings us back,” Pohl says. “It's really a family event, not only with my own family, but the people backstage become a part of your pageant family.”

Pohl recalls how standing still on stage for 90 seconds at a time and maintaining the pose can be challenging.

“If you have an easy pose, the time goes by quickly,” she says. “When I was 14, I posed as the woman in the Columbia Pictures [movie company logo]. I had to hold my arm at a 90-degree angle. Nowadays we have an armature where you can rest your arm, but back then I had to hold my arm up on my own. It wasn't easy, I was screaming inside.”

Matthew Rolston, a Hollywood-based photographer, captured cast members in full makeup and costume for a new exhibition at the Laguna Art Museum called “Matthew Rolston, Art People: The Pageant Portraits,” on view through September 19. In a recent interview with CNN he says, “There is a sense of wonder at the illusion because what they do is so amazingly well crafted. You really think for a few moments that you're looking at an artwork, and then you realize it's human beings that are painting and costumed. It's a simulacra and an illusion—somewhere between humanity and a depiction of humanity. And that has some intrinsic, almost primitive fascination for people.”

That trick of the eye is what Challis Davy strives for, and to keep audiences captivated she tries to include a new artwork each season, she does rely on a few fan favorites that get reused again and again.

“It can be time consuming to make the 3-D sculptures, like the ‘Lincoln Memorial,’” she says. “It’s become a tradition for da Vinci’s ‘The Last Supper’ to be our finale. A seat at the table is coveted, and many of the gentlemen return to the same role from year to year, with some of them appearing in the finale for 25 to 30 years. They may not be the youngest apostles, but their heart is in it, and they love it.”

The Pageant of the Masters runs nightly through September 3.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.