From Playboy to Polar Bears: A Fashion Photographer’s Journey to Document Climate Science in Northernmost Alaska

Florencia Mazza Ramsay traveled to Barrow, the northernmost town in the United States, to document life and research on the front lines of climate change

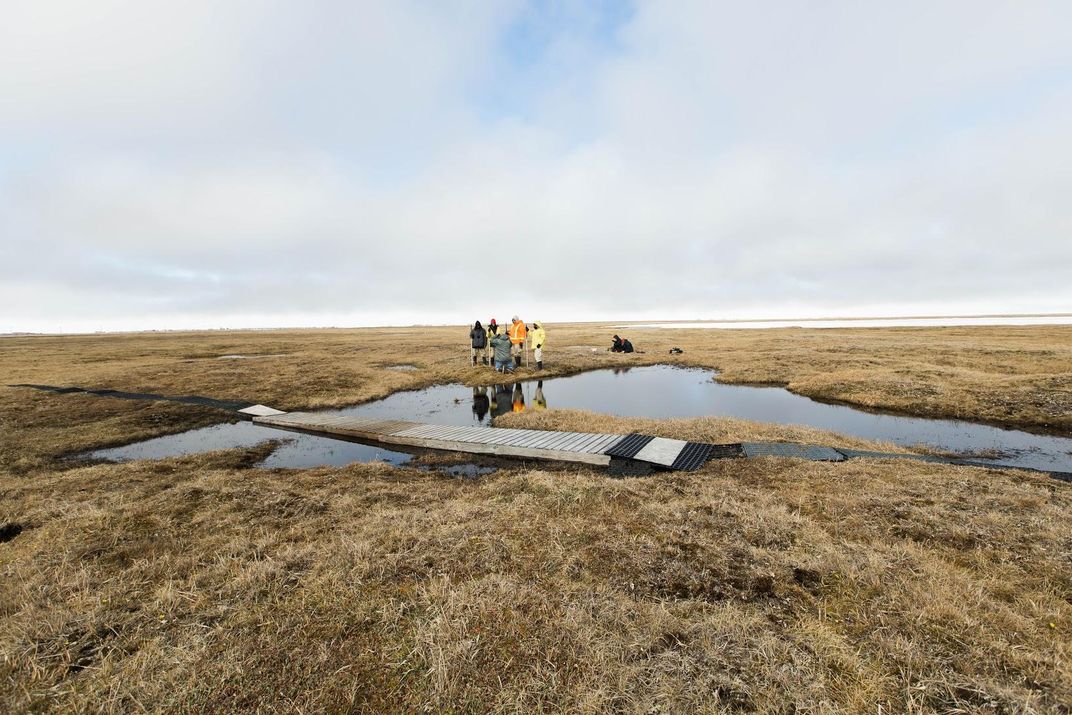

Barrow, Alaska is not the pristine wilderness touted by the American imagination. It is not home to sparkling bays where whales jump against a backdrop of crystal white mountains to the delight of passing cruise ships. Rather, it is northernmost Alaska—“gravel and coast and tundra,” says photographer Florencia Mazza Ramsay. Flat land stretches for miles. The climate is harsh and wild. “It feels like you are in the middle of nowhere and that’s the end of the world and there’s nowhere else to go,” she says.

Mazza Ramsay’s photography credits include Playboy Spain and Porsche, so as she was trekking alongside scientists in Barrow last summer on high alert for polar bears, she paused to consider the contrast.

“I went from five-star hotels and celebrities to carrying a shotgun [for defense] in the Arctic,” she says with a laugh.

Originally from Argentina, Mazza Ramsay now lives in El Paso, Texas, with her husband, a research assistant for Systems Ecology Lab (SEL), whose work includes monitoring coastal erosion in Barrow during the summer months. Through him, Mazza Ramsay learned about the very real impact of climate change in the Arctic town, including an average of 60 feet of coastal erosion in the past decade.

Inspired to share the realities of this far-off place with the El Paso community, she applied for a grant from the University of Texas El Paso, which runs SEL, to document the research being done in Barrow. Project approved, she set out with her husband from June to September 2015.

When the Ramsays arrived, SEL's principal investigator had hoped they would have a chance to see frozen Barrow. “That’s what gets everyone excited and that makes really interesting photos,” Mazza Ramsay explains. “The thing is that we barely got to see the frozen Barrow."

This year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Barrow Observatory observed snowmelt on May 13, the earliest in 73 years of record-keeping. The melt followed a winter that was 11 degrees above normal for the state. According to NOAA, Barrow is one of the last places in the United States to lose snow cover. The effects of earlier ice melts include changes in vegetation as well as wildlife breeding and migration patterns.

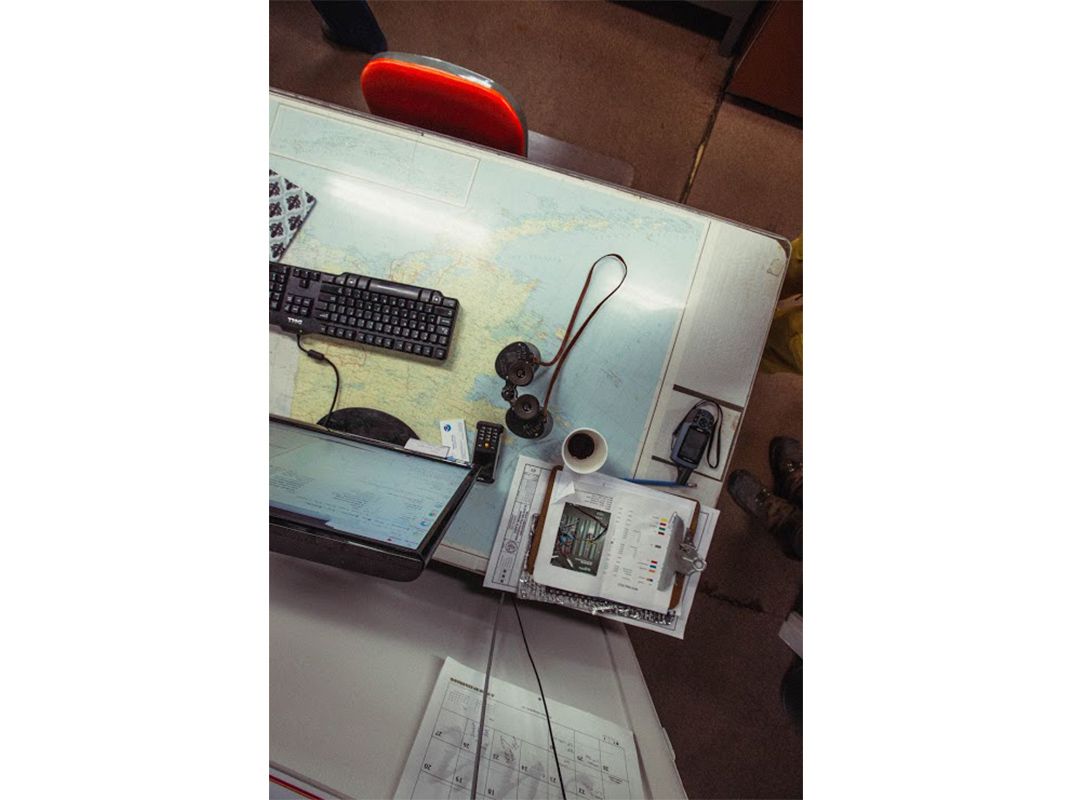

Over the course of four months, Ramsay accompanied scientists from several organizations studying a range of these effects, from erosion to changes in snowy owl habits. A few of the scientists she accompanied had traveled to Barrow for many years and provided her with valuable, firsthand insight into the realities of Barrow’s climate. Among them was George Divoky, who has studied the population of black guillemots, a black and white waterbird, on Cooper Island for more than 40 years.

In that time, Divoky has witnessed many changes to the tiny island off the coast of Barrow. Notably, this summer was the black guillemot’s earliest breeding season yet. While he used to camp on the island, he now lives in a hut to stay away from hungry polar bears and in 2002, he had to be airlifted off the island when polar bears ripped up his tents. Divoky attributes this change to the degradation of the their natural habitat, Arctic pack ice.

Outside of documenting scientific work, Mazza Ramsay engaged with the local community and came to understand the effects of a changing environment on their way of life. From her conversations, she learned that warmer currents and changing sea ice conditions have made conditions more difficult for whalers, who must travel on ice to reach whales and are setting out on their hunts later than usual. This is a significant change, says Mazza Ramsay, due to limited resources in the Arctic tundra: "Barrow culture is rooted deeply in subsisting off the land. People really need to hunt to survive." Elders also shared memories with her of days past when they would sled down now-eroded hills.

Mazza Ramsay hopes that her photographs highlight the importance of climate change beyond political boundaries and put a face to the ways in which scientists are working to understand its effects.

Looking forward, she aspires to return to Barrow to explore the relationship between scientific and local communities. She would like to get a sense of whether the research being done is inspiring for the younger, native generation or viewed as intrusive. Much of the native community is receptive to the scientists’ presence, she explains, but others are wary yet.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2018-08-01_at_7.20.11_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/30/0d303c12-d932-4dc1-891e-e7d9b1dc6a35/coastal-erosion-wr-v1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2018-08-01_at_7.20.11_PM.png)