Behind the Scenes in Monument Valley

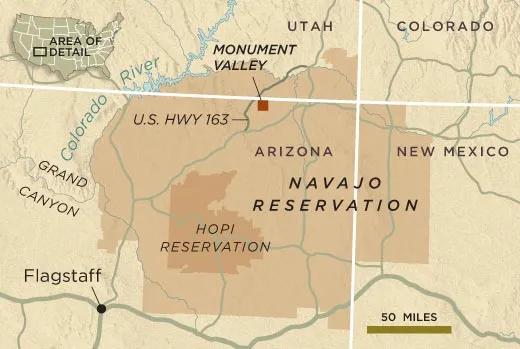

The vast Navajo tribal park on the border of Utah and New Mexico stars in Hollywood movies but remains largely hidden to visitors

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Monument-Valley-Merrick-Butte-631.jpg)

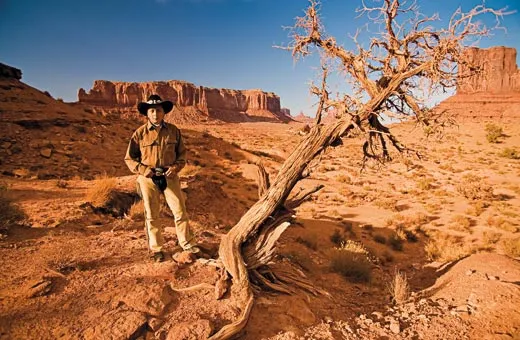

As Lorenz Holiday and I raised a cloud of red dust driving across the valley floor, we passed a wooden sign, “Warning: Trespassing Is Not Allowed.” Holiday, a lean, soft-spoken Navajo, nudged me and said, “Don’t worry, buddy, you’re with the right people now.” Only a Navajo can take an outsider off the 17-mile scenic loop road that runs through Monument Valley Tribal Park, 92,000 acres of majestic buttes, spires and rock arches straddling the Utah-Arizona border.

Holiday, 40, wore cowboy boots, a black Stetson and a handcrafted silver belt buckle; he grew up herding sheep on the Navajo reservation and still owns a ranch there. In recent years, he has been guiding adventure travelers around the rez. We had already visited his relatives, who still farm on the valley floor, and some little-known Anasazi ruins. Now, joined by his brother Emmanuel, 29, we were going to camp overnight at Hunt’s Mesa, which, at 1,200 feet, is the tallest monolith on the valley’s southern rim.

We had set off late in the day. Leaving Lorenz’ pickup at the trail head, we slipped through a hole in a wire stock fence and followed a bone-dry riverbed framed by junipers to the mesa’s base. Our campsite for the night loomed above us, a three-hour climb away. We began picking our way up the rippling sandstone escarpment, now turning red in the afternoon sun. Lizards gazed at us, then skittered into shadowy cracks. Finally, after about an hour, the ascent eased. I asked Lorenz how often he came here. “Oh, pretty regular. Once every five years or so,” he said with a laugh. Out of breath, he added: “This has got to be my last time.”

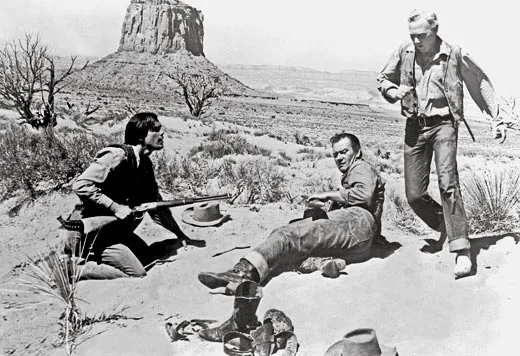

It was dark by the time we reached the summit, and we were too tired to care about the lack of a view. We started a campfire, ate a dinner of steak and potatoes and turned in for the night. When I crawled out of my tent the next morning the whole of Monument Valley was spread out before me, silent in the purple half-light. Soon the first shafts of golden sunlight began creeping down the buttes’ red flanks and I could see why the director John Ford filmed such now-classic westerns as Stagecoach and The Searchers here.

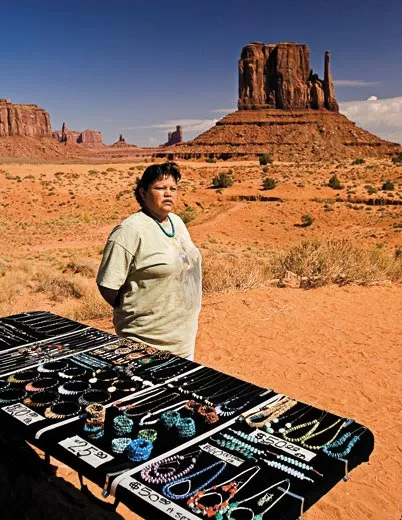

Thanks to Ford, Monument Valley is one of the most familiar landscapes in the United States, yet it remains largely unknown. “White people recognize the valley from the movies, but that’s the extent of it,” says Martin Begaye, program manager for the Navajo Parks and Recreation Department. “They don’t know about its geology, or its history, or about the Navajo people. Their knowledge is very superficial.”

Almost nothing about the valley fits easy categories, starting with its location within the 26,000-square-mile Navajo reservation. The park entrance is in Utah, but the most familiar rock formations are in Arizona. The site is not a national park, like nearby Canyonlands, in Utah, and the Grand Canyon, in Arizona, but one of six Navajo-owned tribal parks. What’s more, the valley floor is still inhabited by Navajo—30 to 100 people, depending on the season, who live in houses without running water or electricity. “They have their farms and livestock,” says Lee Cly, acting superintendent of the park. “If there’s too much traffic, it will destroy their lifestyle.” Despite 350,000 annual visitors, the park has the feel of a mom and pop operation. There is one hiking trail in the valley, accessible with a permit: a four-mile loop around a butte called the Left Mitten, yet few people know about it, let alone hike it. At the park entrance, a Navajo woman takes $5 and tears off an admission ticket from a roll, like a raffle ticket. Cars crawl into a dusty parking lot to find vendors selling tours, horseback rides, silver work and woven rugs.

All this may change. The park’s first hotel, the View, built and staffed mostly by Navajo, opened in December 2008. The 96-room complex is being leased by a Navajo-owned company from the Navajo Nation. In December 2009, a renovated visitors center opened, featuring exhibits on local geology and Navajo culture.

Throughout the 19th century, white settlers considered the Monument Valley region—like the desert terrain of the Southwest in general—to be hostile and ugly. The first U.S. soldiers to explore the area called it “as desolate and repulsive looking a country as can be imagined,” as Capt. John G. Walker put it in 1849, the year after the area was annexed from Mexico in the Mexican-American War. “As far as the eye can reach...is a mass of sand stone hills without any covering or vegetation except a scanty growth of cedar.”

But the valley’s isolation, in one of the driest and most sparsely populated corners of the Southwest, helped protect it from the outside world. There is no evidence that 17th- or 18th-century Spanish explorers ever found it, although they roamed the area and came in frequent conflict with the Navajo, who called themselves Diné, or “The People.” The Navajo lived in an area today known as the Four Corners, where Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico meet. They called Monument Valley Tsé Bii Ndzisgaii, or “Clearing Among the Rock,” and regarded it as an enormous hogan, or dwelling, with the two isolated stone pinnacles to the north—now known as Gray Whiskers and Sentinel—as its door posts. They considered the two soaring buttes known as the Mittens to be the hands of a deity.

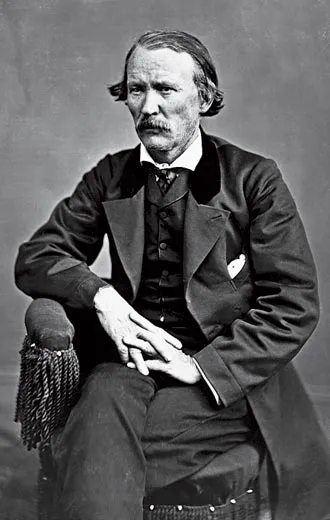

The first non-Indians to stumble upon the valley were probably Mexican soldiers under Col. José Antonio Vizcarra, who captured 12 Paiutes there on a raid in 1822. In 1863, after U.S. troops and Anglo settlers had skirmished with the Navajo, the federal government moved to pacify the area by relocating every Navajo man, woman and child to a reservation 350 miles to the southeast, in Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. But when U.S. soldiers under Col. Kit Carson began rounding up Navajo people for the notorious “Long Walk,” many fled the valley to hide out near Navajo Mountain in southern Utah, joining other Native American refugees under the leadership of Chief Hashkéneinii. The Navajo returned in 1868 when the U.S. government reversed its policy and, through a treaty, gave them a modest reservation along the Arizona-New Mexico border. But Monument Valley was not initially included. It lay on the reservation’s northwestern fringe, in an area used by the Navajo, Utes and Paiutes, and was left as public land.

Travelers from the East were almost nonexistent. In the Gilded Age, American tourists preferred the more “European” Rockies and the forests of California. This began to change in the early 1900s, as Anglo artists depicted Southwestern landscapes in their works, and interest in Native American culture took hold. Indian traders spread reports of Monument Valley’s scenic beauty. Even so, the valley’s remoteness—180 miles northeast of the railway line in Flagstaff, Arizona, a week-long pack trip—discouraged all but the most adventurous travelers. In 1913, the popular western author Zane Grey came to the valley after battling “a treacherous red-mired quicksand” and described a “strange world of colossal shafts and buttes of rock, magnificently sculptured, standing isolated and aloof, dark, weird, lonely.” After camping there overnight, Grey rode on horseback around the “sweet-scented sage-slopes under the shadow of the lofty Mittens,” an experience that inspired him to set a novel, Wildfire, in the valley. Later that same year, President Theodore Roosevelt visited Monument Valley en route to nearby Rainbow Bridge in Utah, where he hiked and camped, and in 1916, a group of tourists managed to drive a Model T Ford into the valley. The second director of the National Park Service, Horace Albright, who thought the area was a possible candidate for federal protection after a 1931 inspection, was among a handful of anthropologists, archaeologists and conservationists who visited it between the world wars. But in Washington interest was minimal. Monument Valley still lacked paved roads, and the unpaved ones were so treacherous they were called “Billygoat Highways.”

Throughout this period, the proprietary rights to Monument Valley kept changing hands. “The land bounced between Anglo and Native American control for decades because of the prospect of finding gold or oil there,” says Robert McPherson, the author of several books about Navajo history. “Only when white people thought it was useless for mining did they finally give it back to the Navajo.” At a meeting in Blanding, Utah, in 1933, a compromise agreement granted the Paiute Strip, part of which is in Monument Valley, to the Navajo Reservation. At last, all of the valley was Navajo land. But the deal that would clinch the valley’s peculiar fate occurred in Hollywood.

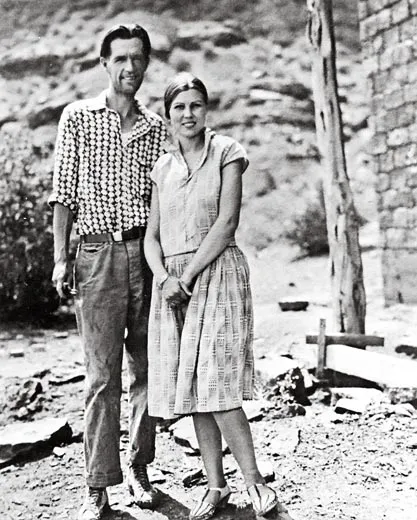

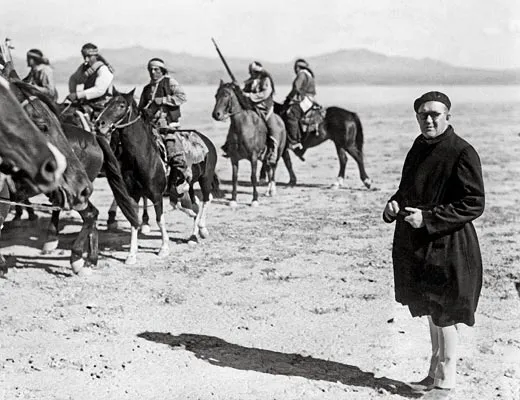

In 1938, a “tall, lanky cowboy in the style of Gary Cooper,” as one studio acquaintance described him, walked into United Artists Studios in Los Angeles and asked a receptionist if he could talk to someone, anyone, about a location for a western movie. Harry Goulding ran a small trading post at the northwest rim of Monument Valley. A Colorado native, Goulding had moved to the valley in 1925, when the land was public, and had become popular with the Navajo for his cooperative spirit and generosity, often extending credit during difficult times. The Depression, a drought and problems created by overgrazing had hit the Navajo and the trading post hard. So when Goulding heard on the radio that Hollywood was looking for a location to shoot a western, he and his wife, Leone, nicknamed Mike, saw a chance to improve their lot as well as the Indians’.

“Mike and I figured, ‘By golly, we’re going to head for Hollywood and see if we can’t do something about that picture,’” he later recalled. They gathered photographs, bedrolls and camping gear and drove to Los Angeles.

According to Goulding, the United Artist receptionist all but ignored him until he threatened to get out his bedding and spend the night in the office. When an executive arrived to throw Goulding out, he glimpsed one of the photographs—a Navajo on horseback in front of the Mittens—and stopped short. Before long, Goulding was showing the images to 43-year-old John Ford and a producer, Walter Wanger. Goulding left Los Angeles with a check for $5,000 and orders to accommodate a crew while it filmed in Monument Valley. Navajos were hired as extras (playing Apaches), and Ford even signed up—for $15 a week—a local medicine man named Hastiin Tso, or “Big Man,” to control the weather. (Ford evidently ordered “pretty, fluffy clouds.”) The movie, released in 1939, was Stagecoach and starred a former stuntman named John Wayne. It won two Academy Awards and made Wayne a star; it also made the western a respected film genre.

John Ford would go on to shoot six more westerns in Monument Valley: My Darling Clementine (1946), Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), The Searchers (1956), Sergeant Rutledge (1960) and Cheyenne Autumn (1964). In addition to introducing the valley’s spectacular scenery to an international audience, each movie pumped tens of thousands of dollars into the local economy. The shoots were usually festive, with hundreds of Navajo gathering in tents near Goulding’s trading post, singing, watching stuntmen perform tricks and playing cards late into the night. Ford, often called “One Eye” because of his patch, was accepted by the Navajo, and he returned the favor: after heavy snows cut off many families in the valley in 1949, he arranged for food and supplies to be parachuted to them.

It’s said that when John Wayne first saw the site, he declared: “So this is where God put the West.” Millions of Americans might agree. The valley soon became fixed in the popular imagination as the archetypal Western landscape, and tourists by the carloads began arriving. In 1953, the Gouldings expanded their two stone cabins into a full-fledged motel with a restaurant manned by Navajo. To cope with the influx (and discourage, among other things, pothunters in search of Anasazi relics), conservation groups proposed making the valley a national park. But the Navajo Nation’s governing body, the Tribal Council, objected; it wanted to protect the valley’s Indian residents and preserve scarce grazing land. In 1958, the council voted to set aside 29,817 acres of Monument Valley as the first-ever tribal park, to be run by Navajo on the national park model, and allocated $275,000 to upgrade roads and build a visitors center. The park is now the most visited corner of the Navajo reservation. “The Navajo Nation were really the trailblazers for other Native American groups to set up parks,” says Martin Link, former director of the Navajo Museum in Window Rock, Arizona, who helped train the first Navajo park rangers in the early 1960s.

Goulding’s Trading Post is now a sprawling complex of 73 motel rooms, a campground and an enormous souvenir shop. (Harry Goulding died in 1981, Mike in 1992.) The original 1925 store has been turned into a museum, displaying film stills and posters from the dozens of movies shot in the valley. Even the Gouldings’ old mud-brick potato cellar, which appeared as the home of Capt. Nathan Brittles (Wayne) in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, remains. A small cinema shows John Wayne movies at night.

For the end of my trip, following my overnight atop Hunt’s Mesa, I decided to camp on Monument Valley’s floor among the most famous monoliths. To arrange this, Lorenz Holiday took me to meet his aunt and uncle, Rose and Jimmy Yazzie, whose farm lies at the end of a spidery network of soft sand roads. The elderly couple spoke little English, so Lorenz translated the purpose of our visit. Soon they agreed to let me camp on a remote corner of their property for a modest fee.

I built a small fire at dusk, then sat alone watching as the colors of the buttes shifted from orange to red to crimson. In the distance, two of the Yazzies’ sons led a dozen mustangs across the valley, the horses kicking up clouds of dust.

John Ford, I imagined, couldn’t have chosen a better spot.

Frequent contributor Tony Perrottet last wrote for the magazine about John Muir’s Yosemite. Photographer Douglas Merriam lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)