The Best Little Museum You Never Visited in Paris

The Museum of Arts and Crafts is a trove of cunning inventions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/31/bd315131-e83d-4efe-b95f-59f50ebbcc9b/42-28766837.jpg)

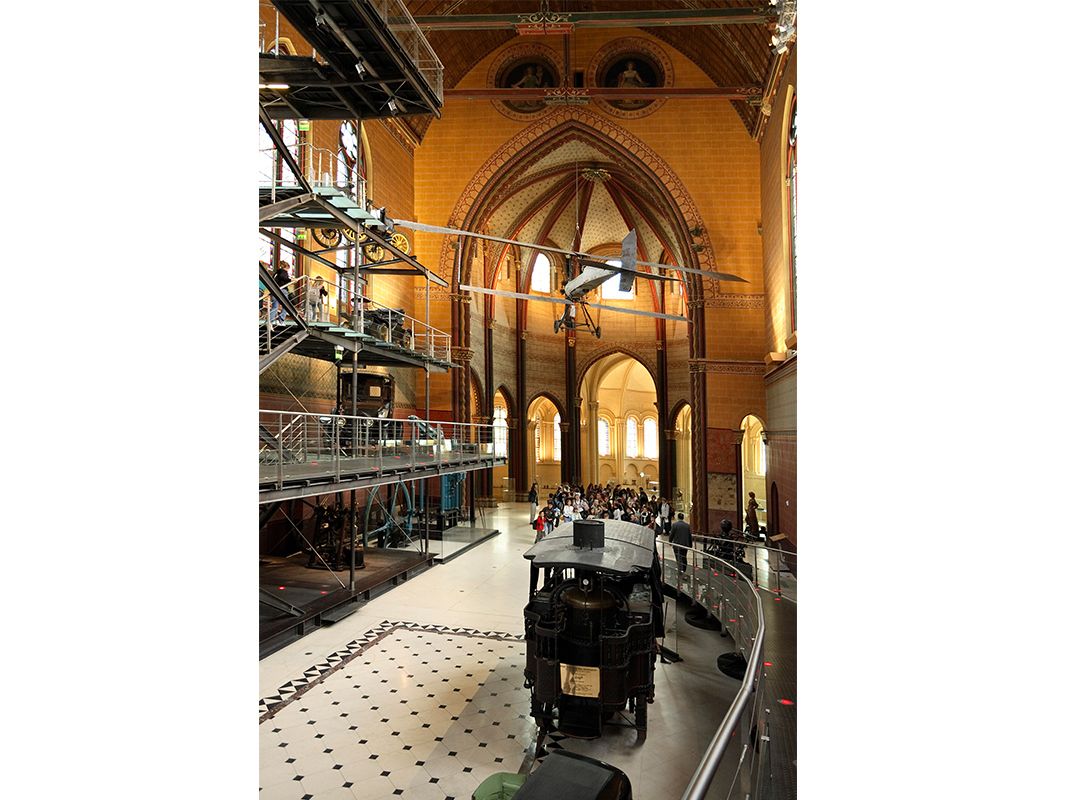

At the heart of Paris, in a former monastery dating back to the Middle Ages, lives an unusual institution full of surprises whose name in French—le Musée des Arts et Métiers—defies translation.

The English version, the Museum of Arts and Crafts, hardly does justice to a rich, eclectic and often beautiful collection of tools, instruments and machines that documents the extraordinary spirit of human inventiveness over five centuries—from an intricate Renaissance astrolabe (an ancient astronomical computer) to Europe’s earliest cyclotron, made in 1937; to Blaise Pascal’s 17th-century adding machine and Louis Blériot’s airplane, the first ever to cross the English Channel (in 1909).

Many describe the musée, which was founded in 1794, during the French Revolution, as the world’s first museum of science and technology. But that doesn’t capture the spirit either of the original Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, created to offer scientists, inventors and craftsmen a technical education as well as access to the works of their peers.

Its founder, the Abbé Henri Grégoire, then president of the revolution’s governing National Convention, characterized its purpose as enlightening “ignorance that does not know, and poverty which does not have the means to know.” In the infectious spirit of égalité and fraternité, he dedicated the conservatoire to the “artisan who has seen only his own workshop.”

In 1800, the conservatoire moved into the former Saint-Martin-des-Champs, a church and Benedictine monastery that had been “donated” to the newly founded republic not long before its last three monks lost their heads to the guillotine. Intriguing traces of its past life still lie in plain view: fragments of a 15th-century fresco on a church wall and rail tracks used to roll out machines in the 19th century.

What began as a repository for existing collections, nationalized in the name of the republic, has expanded to 80,000 objects, plus 20,000 drawings, and morphed into a cross between the early cabinets de curiosités (without their fascination for Nature’s perversities) and a more modern tribute to human ingenuity.

“It is a museum with a collection that has evolved over time, with acquistions and donations that reflected the tastes and technical priorities of each era,” explained Alain Mercier, the museum’s resident historian. He said the focus shifted from science in the 18th century to other disciplines in the 19th: agriculture, then industrial arts, then decorative arts. “It was not rigorously logical,” he added.

Mostly French but not exclusively, the approximately 3,000 objects now on view are divided into seven sections, beginning with scientific instruments and materials, and then on to mechanics, communications, construction, transport, and energy. There are displays of manufacturing techniques (machines that make wheels, set type, thread needles, and drill vertical bores) and then exhibits of the products of those techniques: finely etched glassware, elaborately decorated porcelains, cigar cases made of chased aluminum, all objects that could easily claim a place in a decorative arts museum.

The surprising juxtaposition of artful design and technical innovation pops up throughout the museum’s high-ceilinged galleries—from the ornate, ingenious machines of 18th-century master watchmakers and a fanciful 18th-century file-notching machine, shaped to look like a flying boat, to the solid metal creations of the industrial revolution and the elegantly simple form of a late 19th-century chainless bicycle.

Few other museums, here or abroad, so gracefully celebrate both the beautiful and the functional—as well as the very French combination of the two. This emphasis on aesthetics, particularly evident in the early collections, comes from the aristocratic and royal patrons of pre-revolution France who placed great stock in the beauty of their newly invented acquisitions. During this era, said Mercier, “people wanted to possess machines that surprised both the mind and the eye.”

From this period come such splendid objects as chronometers built by the royal clockmaker Ferdinand Berthoud; timepieces by the Swiss watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet; a finely crafted microscope from the Duc de Chaulnes’s collection; a pneumatic machine by the Abbé Jean-Antoine Nollet, a great 18th-century popularizer of science; and a marvelous aeolipile, or bladeless radial steam turbine, which belonged to the cabinet of Jacques Alexandre César Charles, the French scientist and inventor who launched the first hydrogen-filled balloon, in 1783.

Christine Blondel, a researcher in the history of technology at the National Center of Scientific Research, noted that even before the revolution, new scientific inventions appeared on display at fairs or in theaters. “The sciences were really part of the culture of the period,” she said. “They were attractions, part of the spectacle.”

This explains some of the collection’s more unusual pieces, such as the set of mechanical toys, including a miniature, elaborately dressed doll strumming Marie Antoinette’s favorite music on a dulcimer; or the famous courtesan Madame de Pompadour’s “moving picture” from 1759, in which tiny figures perform tasks, all powered by equally small bellows working behind a painted landscape.

Mercier, a dapper 61-year-old who knows the collection by heart and greets its guards by name, particularly enjoys pointing out objects that exist solely to prove their creator’s prowess, such as the delicately turned spheres-within-spheres, crafted out of ivory and wood, which inhabit their own glass case in the mechanics section. Asked what purpose these eccentric objects served, Mercier smiles. “Just pleasure,” he responds.

A threshold moment occurred in the decades leading up to the revolution, notes Mercier, when French machines began to shed embellishment and become purely functional. A prime example, he says, is a radically new lathe—a starkly handsome metal rectangle—invented by engineer Jacques Vaucanson in 1751 to give silk a moiré effect. That same year Denis Diderot and Jean-Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert first published their Encyclopedia, a key factor in the Enlightenment, which among many other things celebrated the “nobility of the mechanical arts.” The French Revolution further accelerated the movement toward utility by standardizing metric weights and measures, many examples of which are found in the museum.

When the industrial revolution set in, France began to lose its leading position in mechanical innovation, as British and American entrepreneurial spirit fueled advances. The museum honors these foreign contributions too, with a French model of James Watt’s double-acting steam engine, a 1929 model of the American Isaac Merritt Singer’s sewing machine and an Alexander Graham Bell telephone, which had fascinated visitors to London’s Universal Exhibition in 1851.

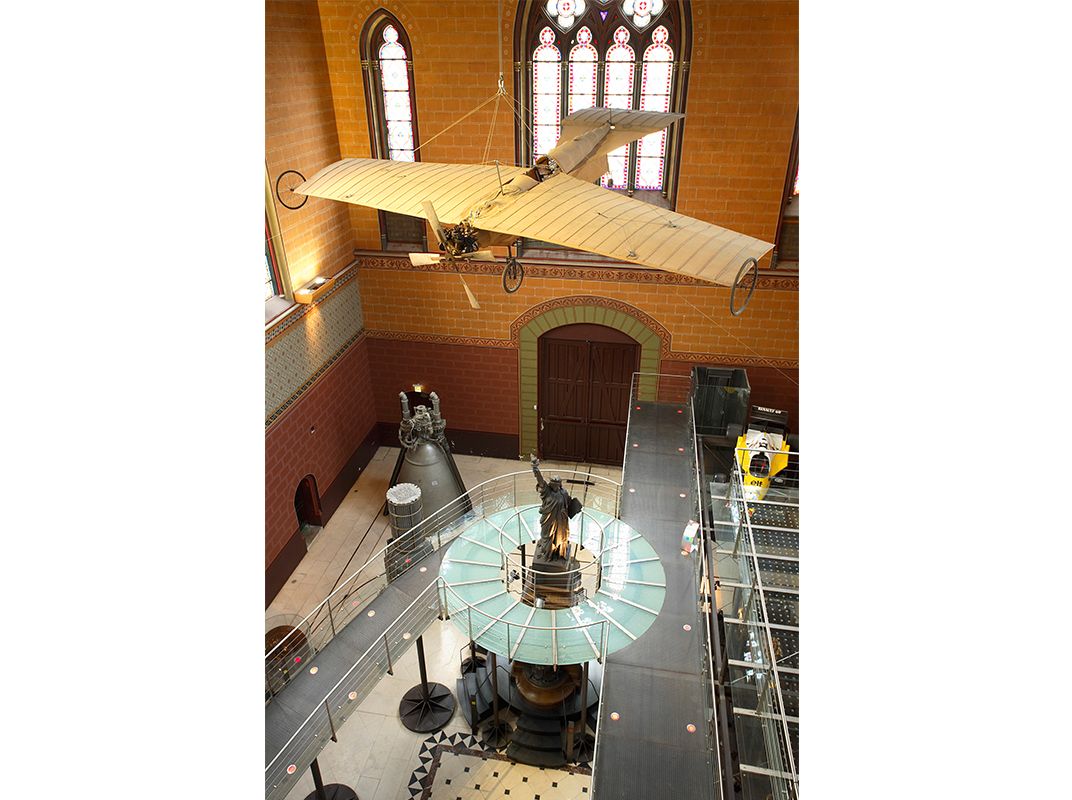

Even so, France continued to hold its own in the march of industrial progress, contributing inventions such as Hippolyte Auguste Marinoni’s rotary printing press, an 1886 machine studded with metal wheels; the Lumière brothers’ groundbreaking cinematograph of 1895; and, in aviation, Clément Ader’s giant, batlike airplane.

Although the museum contains models of the European Space Agency’s Ariane 5 rocket and a French nuclear power station, the collection thins out after World War II, with most of France’s 20th-century science and technology material on display at Paris’s Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie.

Few sights can top the Arts et Métiers’ main exhibit hall located in the former church: Léon Foucault’s pendulum swings from a high point in the choir, while metal scaffolding built along one side of the nave offers visitors an intriguing multistoried view of the world’s earliest automobiles. Juxtaposed in dramatic midair hang two airplanes that staked out France’s leading role in early aviation.

For all its unexpected attractions, the Musée des Arts et Métiers remains largely overlooked, receiving not quite 300,000 visitors in 2013, a fraction of the attendance at other Paris museums. That, perhaps, is one of its charms.

Parisians know it largely because of popular temporary exhibits, such as “And Man Created the Robot,” which showcased in 2012-13. These shows have helped boost attendance by more than 40 percent since 2008. But the museum’s best advertisement may be the stop on Métro Line 11 that bears its name. Its walls feature sheets of copper riveted together to resemble the Nautilus submarine in Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, complete with portholes.

For anyone looking for an unusual Paris experience, the station—and the museum on its doorstep—is a good place to start.

Six Exhibits Not to Miss

Ader Avion No. 3

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/9d/5e9de49e-8e21-4083-8461-657ada8bd0d6/sqj_1504_paris_science_04-web-resize.jpg)

Six years before the Wright brothers’ famous flight, French inventor and aviation engineer Clément Ader won a grant from France’s war office to test his batlike Avion No. 3 flying machine at the Satory army base near Versailles. Powered by two alcohol-burning steam engines, which moved two propellers, each with four feathery blades, the monstrous creation stood no chance of flight, even though an earlier version had lifted slightly off the ground. Underpowered and lacking a flight control system, the No. 3 swerved off the base’s track when hit by a gust of wind while taxiing and stopped. The war office withdrew its funding.

Ader did not quit aviation, going on to write an important book that presciently described the modern aircraft carrier. He donated Avion No. 3 to the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers in 1903, the year the Wright brothers achieved controlled, heavier-than-air flight. It hangs above a classical 18th-century staircase, a testament to Victorian curiosity and inventiveness.

Pascaline

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/d3/ded3fbc6-ad94-4b51-bfbc-7d9761d81239/sqj_1504_paris_science_05-web-resize.jpg)

As a teenager, Blaise Pascal invented one of the world’s first mechanical calculators, eventually known as a Pascaline, in 1645. His father, a tax official at Rouen, in Normandy, laboriously counted using an abacus, an ancient technique that drove the child prodigy to distraction. Pascal created a series of gears that could automatically “carry over” numbers, enabling the operator to add and subtract. (When one gear with ten teeth completed a full revolution, it in turn moved another gear by only one tooth; a hundred turns of the first gear moved the second to revolve fully itself, turning a third gear by one tooth, and so on, a mechanism still used in car odometers and electrical meters today.)

Pascal went through 50 prototypes before producing 20 machines, but the Pascaline would never prove a commercial success. Pascal’s genius would flower in revolutionary publications in philosophy and mathematics before his death at 39. The Musée des Arts et Métiers has four Pascalines on display, including one that the inventor sent to Sweden’s Queen Christina.

Lion and the Snake

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/40/ba4022dd-993d-4a5b-9996-0a672e6348a5/sqj_1504_paris_science_06.jpg)

A giant snake wraps threateningly around the life-size figure of a lion, an arrestingly lifelike statue made—surprisingly—of spun glass. Master French enameller René Lambourg finished the eight-year project in 1855, then wowed both the jury and visitors at Paris’s Universal Exposition that same year. Lambourg fashioned glass threads between one- and three-hundredths of a millimeter in diameter, then heated them, which created strands as workable as fabric. A long tradition of émailleurs ended with Lambourg’s death, much of the enameling tradecraft disappearing with him, but the museum was fortunate to acquire the masterpiece in 1862.

Lavoisier's Laboratory

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/f0/0ef03265-b817-48f8-902c-3dd380207929/sqj_1504_paris_science_07.jpg)

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier, the father of modern chemistry, is shown (right) with his wife, Marie-Anne Paulze, in an 18th-century painting. At the museum, visitors can see Lavoisier’s wood-panelled laboratory, in which he recognized and named the terms “oxygen” and “hydrogen,” discovered the law of conservation of mass and created the first extensive list of elements, eventually leading to the periodic table. He also invented scales precise enough to measure the equivalence of a kilogram, a gasometer and a calorimeter capable of measuring body heat. Lavoisier used some 13,000 instruments in his laboratory.

Under the ancien régime, Lavoisier served as an administrator of the Ferme Générale, a tax-collecting operation on behalf of the king, a position that led to his execution by guillotine in 1794, the year the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers was founded.

His widow not only served as an able assistant but also made important contributions by translating critical English treatises for her husband. She continued his legacy by preserving the laboratory and its instruments, on full display at the museum.

Émile Gallé Vase

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/b7/e0b70e19-eaf1-4710-8372-ed8060a52f54/sqj_1504_paris_science_08-web-resize.jpg)

Master glassmaker Émile Gallé created the striking crystal vase “La Nigelle” in 1900, an exemplar of the art deco movement, which he greatly influenced. He originated a technique for cutting and incising plant motifs onto heavy, smoked glass or translucent enamels, often in multiple colors.

“La Nigelle” and multiple other Gallé pieces reside in the museum within a display case specially created for the collection, which includes a base decorated in marquetry that shows glassblowing, molding, and acid engraving scenes from the Gallé crystal works in Nancy. The museum’s Materials section also contains works by other famous French glass masters, such as a delicate, three-tiered Baccarat crystal filigree stand, made in approximately 1850.

Foucault’s Pendulum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/6f/2e6ffa24-42d4-4310-a9c8-e5f3cbd3e2ed/swj_1504_paris_science_09r1.jpg)

In 1851 French physicist Léon Foucault hung his new pendulum, consisting of a 60-pound, brass-coated bob swinging from a 230-foot cable, from the ceiling of the Panthéon on Paris’s Left Bank. Huge crowds flocked to see the invention, the first ever device to demonstrate clearly the Earth’s rotation using laboratory apparatus rather than astronomical observations. The gentle swing remains at a generally fixed point (depending on the latitude where the device is placed) as the viewers and Earth rotate beneath it.

A reconstituted version of the original now swings from the vaulted ceiling of the museum’s exhibit hall (formerly the Saint-Martin-des-Champs priory). Although a simple device, the physics can be challenging, but well-informed guides are available with explanations. The 19th-century experiment, now reproduced throughout the world, gained new notoriety with the 1988 publication of the Italian author Umberto Eco’s novel Foucault’s Pendulum, speculative fiction with occult conspiracy theories that centers on the pendulum.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.