Beyond the Wall: Berlin

Nearly 17 years after the wall came down, Berliners are still trying to escape its shadow

The Berlin morning was gray and drizzly, October 3, 2005, and the thin crowds milling outside the Brandenburg Gate were in no mood to celebrate the 15th annual Day of German Unity. Recent news suggested why: unemployment and the budget deficit were soaring, consumer confidence and birthrates were plunging, and economic growth was dismally flat. Berlin itself seemed to underscore the failure of the country’s reunification: over the past 15 years unemployment in the city had doubled to 20 percent, and civic debt had grown fivefold to a crushing $68 billion. Germany’s general elections 15 days before, widely expected to produce a new chancellor and fresh emphasis on economic and social reforms, had instead ended in a deadlock with the existing government, suggesting that the Germans feared the cure as much as the disease.

Even the October date was wrong. The real red-letter day had been November 9, 1989, when the Berlin Wall was first breached. I had been in Berlin that day and had seen a very different celebration. Citizens of the two hostile states had walked arm in arm like wide-eyed dreamers along the 200-yard stretch between the bullet-riddled Reichstag in the West and the smog-blackened Brandenburg Gate in the East. Berliners had danced on the hated wall, weeping openly and chanting, “We are one people!” Now the crowd was listless, the Reichstag and the Brandenburg Gate, recently restored, shone pearly-white. And between them the wall might never have existed.

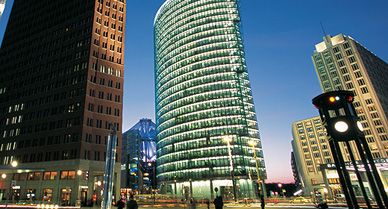

Only when I began to search for some trace of it did I notice a line of bricks at my feet. This, evidently, was where the 26-mile barrier, Berlin’s blight for 28 years, had stood. As I started walking south along the wall line, the bricks zigzagged under the currywurst stands and marionette stalls of the reunification festival, slipped beneath the traffic on Ebertstrasse, and sliced through the new skyscrapers in Potsdamer Platz—the huge square that had been one of Berlin’s gems before Allied bombing in World War II turned much of it to rubble, and before the wall made it a no man’s land. Here, 30 minutes into my walk, I passed four concrete slabs, the first pieces of the actual wall I had seen. Painters had festooned them with naif figures and cherry-red hearts, making them look more like found art than the remains of a deadly barrier.

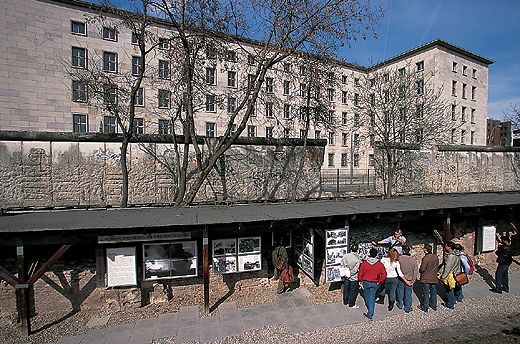

It wasn’t until the line of bricks left the tumult of Potsdamer Platz and turned onto the silent Niederkirchnerstrasse that the dreaded structure began to assert itself. A stretch of the wall rose up from the bricks, iron gray and some 13 feet tall, its rounded top designed to foil grappling hooks. This stretch of wall, a sign said, bordered the former Gestapo headquarters and prison complex at Prinz Albrechtstrasse 8, once the most feared address in Berlin. The headquarters had been demolished in the mid-1950s, but in 1986, when the area was excavated in preparation for redevelopment, parts of the Gestapo’s underground torture chambers came to light. West Berliners hurried to the site, and it became an open-air memorial to the horrors of the Nazi regime. Today, the cell walls contain photographs of the murdered: Communists, artists, gypsies, homosexuals and, of course, Jews. In one photo, a Jewish shopkeeper swept debris from the pavement in front of his plundered store, on the morning after Kristallnacht, “the night of broken glass,” when gangs of young Nazis marauded through Berlin’s Jewish neighborhoods on November 9, 1938.

Now it was clear why Berliners did not commemorate the wall’s collapse on the day it fell: November 9 had been permanently tainted by Kristallnacht, just as this vacant lot in the heart of the city had been poisoned by its history, and was now as unusable as the radioactive farmlands of Chernobyl.

Berlin is a palimpsest of old guilt and new hope, where even a cityscape you think you know well can suddenly reveal its opposite. “Beware Berlin’s green spaces!” local author Heinz Knobloch once wrote: parks and playgrounds still rest on air-raid bunkers too massive to destroy. Companies that contributed to the Holocaust still operate: DeGussa AG, manufacturer of the anti-graffiti coating applied to Berlin’s recently inaugurated Holocaust Memorial, also made the Zyklon B poison used in death-camp gas chambers.

As Berlin has done several times in its long history, the city is rebuilding itself, at Potsdamer Platz in avant-garde shapes of glass and steel, and elsewhere in new social structures, communities of artists and intellectuals where life seems as freewheeling as a traveling circus. There is a roominess here that no other European capital can match—Berlin is nine times larger in acreage than Paris, with less than one third of the population—and an infectious sense of anything goes.

By 1989, West Berlin was spending some $365 million a year on culture, more than the U.S. government spent on culture for the entire United States. Most of the beneficiaries of this civic largesse survived reunification; today Berlin boasts 3 world-class opera houses, 7 symphony orchestras, 175 museums, 1,800 art galleries and 2 zoos with more wild animals than any city in the world.

The city is still finding its identity and is a place of almost impossible contradictions: fixated with the past yet impatiently pursuing the future, impoverished yet artistically rich, a former capital of dictatorship and repression that has become a homeland of social freedom. But more than anything, Berlin is filled with—obsessed with—reminders of its history.

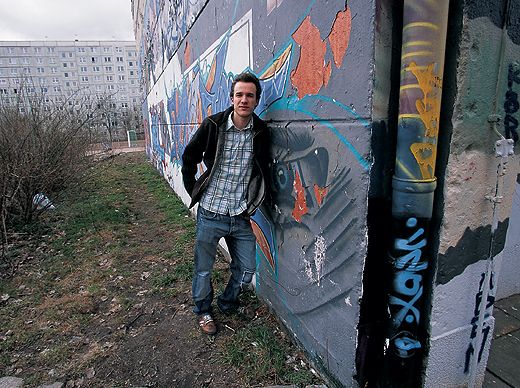

The wall was never a single barrier but three separate ramparts, sealing off a no man’s land of guard towers, patrol roads and razor wire known as the Todesstreifen, or “Death Strip,” which in places was hundreds of yards wide. Since reunification, the Death Strip has grown a varied crop. Back in Potsdamer Platz, the strip sprouted the cranes and buildings of a 300-acre, $5 billion business and entertainment complex. Only a 20-minute walk away, the Death Strip has become a green belt of parks and overgrown lots that feel like the countryside. The brick line faltered and disappeared, and I continued tracking the wall with the help of my city map, which marked its path in pale gray. I was often unsure whether I was in East or West Berlin. Near the Spree River, 40 minutes from Potsdamer Platz, the fields became still wider and wilder. Squatter communities have grown up, neat, ingeniously jury-rigged dwellings that ring to the sound of power tools and folk music and produce the scent of grilling meat.

Wall-hunting for the rest of the day, I found new life in old ruins along its route: a public sauna and swimming area in an abandoned glass factory, a discothèque in a former Death Strip guard tower, a train station converted into an art museum. But the telltale distinctions between East and West endure. The “walk” and “don’t walk” signs remain unchanged since reunification: while the stick figures of the West resemble those of other European capitals, in the former East Berlin the little green man wears a broad-brimmed hat and steps out jauntily, and his red alter ego stands with arms flung wide like the Jesus of Rio. Most buildings are still oriented to the now-invisible barrier: major roads parallel it, with the few cross-wall interconnections still freshly paved. Even footpaths run along the Death Strip. It takes more than a handful of years to remap 26 miles of cityscape, and to change the habits of a lifetime.

Night had fallen by the time I returned to the party at the Brandenburg Gate. People had drunk copious quantities of beer since morning but had grown no merrier. Berliners had lived with the wall for three generations and could not be expected to forget it as easily as one shakes off a nightmare. During the cold war, doctors had identified a range of anxieties and phobias they called Mauerkrankheit (“wall sickness”) on both sides of the divide, and suicide in West Berlin was twice as frequent as in other West German cities. How deeply in the minds of most Berliners do the wall’s foundations still lie?

The crowd fell silent as a Chinese woman in a white silk gown raised a cleaver and slammed it down on the dark brown hand resting on the table before her, severing the index finger. With fierce chops she amputated the other digits and put them on a plate, which she passed among the applauding onlookers. I took the beautifully shaped thumb and bit off a chunk. The dark chocolate was delicious.

This is DNA, one of the many galleries on the Auguststrasse, heart of Berlin’s flourishing contemporary art scene, where most facades have just been restored, but World War II bullet holes and bombed-out lots still lend a certain edginess. DNA’s art is vintage Berlin: quirky, theatrical and as dark as the edible hand-sculptures by Ping Qiu.

Some 1,500 cultural events take place each day in Berlin, thanks to artists like Ping Qiu and her DNA colleagues, who live and make art in the uninhabited buildings in the former eastern sector that are inconceivably large, cheap and central by the standards of any other European capital. They have studios in disused hat factories and industrial bakeries, and hold exhibitions in the numerous air-raid bunkers that still dot the Berlin subsoil. In fact, by splitting the city into two independent halves that actively financed their own venues, the wall fostered Berlin’s culture long before it fell.

The post-wall construction boom has also brought many of the world’s leading architects to Berlin. The city’s residents are deeply involved in this reconstruction process. “You could spend 300 days a year in public discussion about urban planning,” says Michael S. Cullen, a building historian and the world’s leading authority on the Reichstag, who has lived in Berlin since 1964. The attention to art and architecture is what many residents love best about their city. “Berlin is one of the few places I know where ideas can make a concrete difference in daily life,” says philosopher Susan Neiman, head of a think tank, the Einstein Forum.

The wall has also molded Berlin’s populace. The wall caused a sudden labor shortage in both halves of the city when it was erected in 1961, and invited substitute workers poured in. (West Berlin drew from Turkey and other Mediterranean countries; East Berlin from North Vietnam, Cuba and other Communist nations.) People from more than 180 nations live in Berlin. And since the wall fell, tens of thousands of Jewish immigrants—drawn by Berlin’s security, cosmopolitanism, low rents and the incentives the reunited city has extended to all Jews and their descendants displaced by the Holocaust—have streamed to Berlin, most from the former Soviet Union. Yiddish theaters and kosher restaurants thrive in the city, and the mournful sounds of klezmer music can be heard again in the streets after a silence of 70 years.

Today many of Berlin’s Jews live in Russian-speaking enclaves cut off from mainstream society. Periodic acts of anti-Semitism by small but vociferous groups of right-wing extremists have further emphasized the isolation, as have the resulting 24-hour police guards at Jewish community centers and synagogues with their imposing security walls. Many members of Berlin’s 150,000-strong Turkish community live in ethnic ghettos with hardly a word of German. The insularity of Berlin’s Muslims has been highlighted of late by a string of six so-called “honor killings” of Muslim women by relatives who believed the victims’ Western lifestyles had stained their families’ honor. Sarmad Hussain, a German-born Muslim who is a parliamentary adviser in Berlin, says the city’s version of multiculturalism is less melting pot than a relatively benign form of apartheid. “We in Berlin,” he says, “should benefit from all this diversity.” But with most ethnic groups sticking to themselves, he adds: “We don’t.”

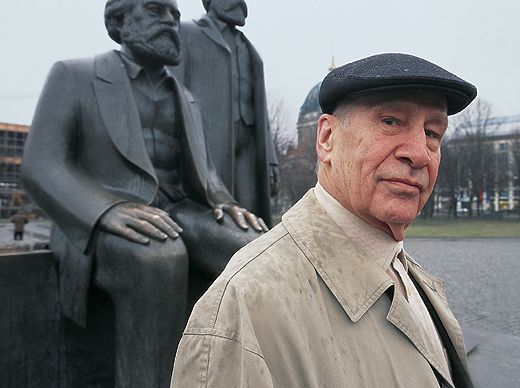

Back in 1981, when the wall seemed eternal, Berlin novelist Peter Schneider observed how fundamentally the two opposing social systems of East and West had shaped their citizens, and mused on the enormous difficulties that any attempt at reunification would meet. “It will take us longer to tear down the Mauer im Kopf (‘Wall in the head’),” he wrote, “than any wrecking company will need to remove the Wall we can see.” Schneider’s words proved prophetic. Berlin’s greatest challenge lies within: to unite those two radically different races of Berliners who, on the night of November 9, 1989, were magically converted—at least on paper—from bitter enemies to compatriots.

Like the traces of the wall itself, the differences between Ossi (East Berliners) and Wessi (West Berliners) have faded. “At first you could recognize the Ossis easily from their marble-washed jeans straight from Siberia or China,” says Michael Cullen. “But even today I can usually recognize them by their clothes, comportment, posture and their slightly downtrodden air.” Also, the two groups shop at different stores, smoke different brands of cigarettes, vote for different political parties and read different newspapers—Ossis, their beloved Berliner Zeitung, Wessis, the Tagespiegel and Berliner Morgenpost. By and large they have remained in their original neighborhoods. Ossis are frequently paid less and required to work more hours in the same job, and are more likely to be unemployed.

All the strains of cold war Europe and of divided Germany were concentrated in one city, along the fault line of the wall, where rival geopolitical systems ground together with tectonic force. On both sides, the reaction was negation. West Germany never recognized East Germany as a nation, nor the wall as a legal border. Eastern maps of Berlin depicted the city beyond the wall as a featureless void, without streets or buildings. Each side built a city in its own image: East Berlin erected towering statues to Marxist heroes and raised signature socialist buildings such as the Palast der Republik, the parliament headquarters. (Demolition was begun earlier this year to make way for a replica of a castle that stood on the spot until 1950.) West Berlin built temples to capitalism on the glittering Kurfürstendamm, such as the Europa Center office tower crowned by a revolving Mercedes emblem.

When the East finally imploded, Wessis filled the vacuum with a speed and thoroughness that, to many easterners, smacked of colonization, even conquest. In Berlin, this process was particularly graphic. Westerners took over top posts in East Berlin’s hospitals and universities, imposed western taxes and laws and introduced western textbooks in schools. Streets and squares once named for Marxist heroes were rebaptized, socialist statues were toppled and iconic buildings of East Berlin were condemned and demolished. Along the wall, the monuments to fallen border guards were swiftly removed. But West Berlin’s buildings and monuments still stand. So do the memorials along the wall to the 150 East Germans killed while trying to escape to the other side. Easterners these days have little choice but to acknowledge the existence of the West. Westerners still appear bent on denying that East Berlin ever was.

Yet the Ossis are still here. As the architectural symbols of East Berlin have fallen to the wrecking ball, the Ossis have protested, sometimes with a force that betrays the tensions in this schizophrenic city. And Ossis of radically different backgrounds frequently express mistrust of the values of modern-day Berlin, a city whose future they feel powerless to shape. “Unfortunately, East Germany failed utterly to live up to its ideals,” said Markus Wolf, the 82-year-old former head of the dreaded Stasi, East Germany’s secret state police. “But for all the shadowy sides, we had a vision of a more just society, an aim of solidarity, trustworthiness, loyalty and friendship. These public ideals are absent today.” For me, his words had the ring of apparatchik rhetoric until I heard them again from Wolf’s polar opposite. “It’s good to encourage a competitive spirit, but not at the expense of the common good,” said 43-year-old novelist Ingo Schulze, one of Germany’s foremost writers, whose books are steeped in the sorrow and disorientation that the Stasi and other organs of state repression helped to create. “Obviously, I’m happy that the wall is gone, but that doesn’t mean we’re living in the best of all possible worlds.” Christian Awe, one of the artists I met at DNA, was 11 when the wall fell, so his memories of East Berlin are less political and more personal. “Back then the aim was to excel for your community, your school, your group, not purely for individual achievement. Today you must be the best, first, greatest, get the best job, have as many lovers as you can.”

These are the voices of a lost Berlin, citizens of a city that vanished the night the wall fell, who are still searching for a homeland. They speak of great gains but also of a loss that is central to life in Berlin, where on the surface the past can be swept away in a handful of years, but whose foundations lie as deep and immovable as a bunker.

As the last fragments of the wall are torn down or weather away, a few leading Berliners have proposed erecting a new memorial on Bernauerstrasse, in north-central Berlin. Perhaps the time has come for such a thing. “We want to make an attempt, within the limits of the possible, to reconstruct a couple hundred meters of the wall,” Berlin mayor Klaus Wowereit told me, “so that one can get a little bit of an idea of it.”

Few of Wowereit’s fellow citizens support his plan, however. Most Ossis and Wessis, for all their differences, were overjoyed at the wall’s obliteration and still feel that it deserves no commemoration. Yet oddly, the explanations they usually give for opposing a memorial are mistaken. Most say the wall could never have been preserved, because it was swept away by the jubilant, hammer-wielding hordes shortly after November 9, 1989. In fact, the bulk of the demolition was done later, by 300 East German border police and 600 West German soldiers, working with bulldozers, backhoes and cranes; it was not a spontaneous act of self-liberation, therefore, but a joint project of two states. With a similar slip of memory, many Berliners say the wall is unworthy of remembrance because it was imposed on them by the Russians. Actually, East German leaders lobbied Khrushchev for years to let them build the wall, and it was Germans who manned the guard towers, Germans who shot to kill. If Berliners don’t want a wall memorial, perhaps they still can’t see the wall for what it truly was.

When the few proponents of a memorial describe what it would mean, they reveal the most pernicious misconception of all. “The central aim will be to commemorate the victims of the wall and the division of Berlin,” Mayor Wowereit said, “particularly those people who died during attempts to escape, and fell victim to the repressive structure of the dictatorship.” Yet surely a wall memorial would also commemorate the millions who never approached the barrier, and went about their cramped lives amid the soft-coal fogs and swirling suspicions of East Germany. It would remind Berliners not to deny but to accept their former divisions, perhaps even celebrate the diversity that the wall, paradoxically, has wrought. And it would warn against the longing for a monolithic unity that many Germans now feel, a longing that in the past has led to some of the darkest moments in their history. When Berliners can build such a memorial to their wall—without victors or vanquished, without scapegoats—they may also be able to see the present with a stranger’s eyes, recognizing not only the hardships of the past tumultuous 15 years but also the remarkable new city they are building.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.