The Biggest Tree Canopy on the Planet Stretches Across Nearly Five Acres

In remote India, a visit to Thimmamma Marrimanu offers a spectacular lesson in the vital coexistence of living things

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/17/461769ca-7447-4cdf-821b-e39c2704c1b6/apr2017_g03_banyantree-wr.jpg)

The road to Thimmamma Marrimanu leads through one of the driest parts of India. I picked it up in a town called Kadiri and drove another hour through camelback mountains and peanut fields. Granite boulders covered the brown landscape like a crumble topping. Nature had been stingy with the flora—saving up, perhaps, so it could splurge on my destination. “Thimmamma Marrimanu is one of the superlative organisms of the planet,” a treetop biologist named Yoav Daniel Bar-Ness told me before I left.

Bar-Ness knows more about the magnitude of giant banyans than just about anyone. Between 2008 and 2010, while working on a project called Landmark Trees of India, he measured the canopies of the most enormous banyans in the country. Seven of them were broader than any other known trees on earth. Thimmamma Marrimanu had the widest spread, with a canopy of nearly five acres. The tree is about 100 miles north of Bangalore, India’s third-largest city, but there’s no mention of it in the popular travel guides. There are no hotels nearby, just a basic guesthouse kept by the state tourism department in the tiny village around the tree. Its windows look out on the banyan, but an uninformed visitor might easily miss the tree for the forest: Thimmamma Marrimanu’s roots and branches spread in every direction, appearing like a grove.

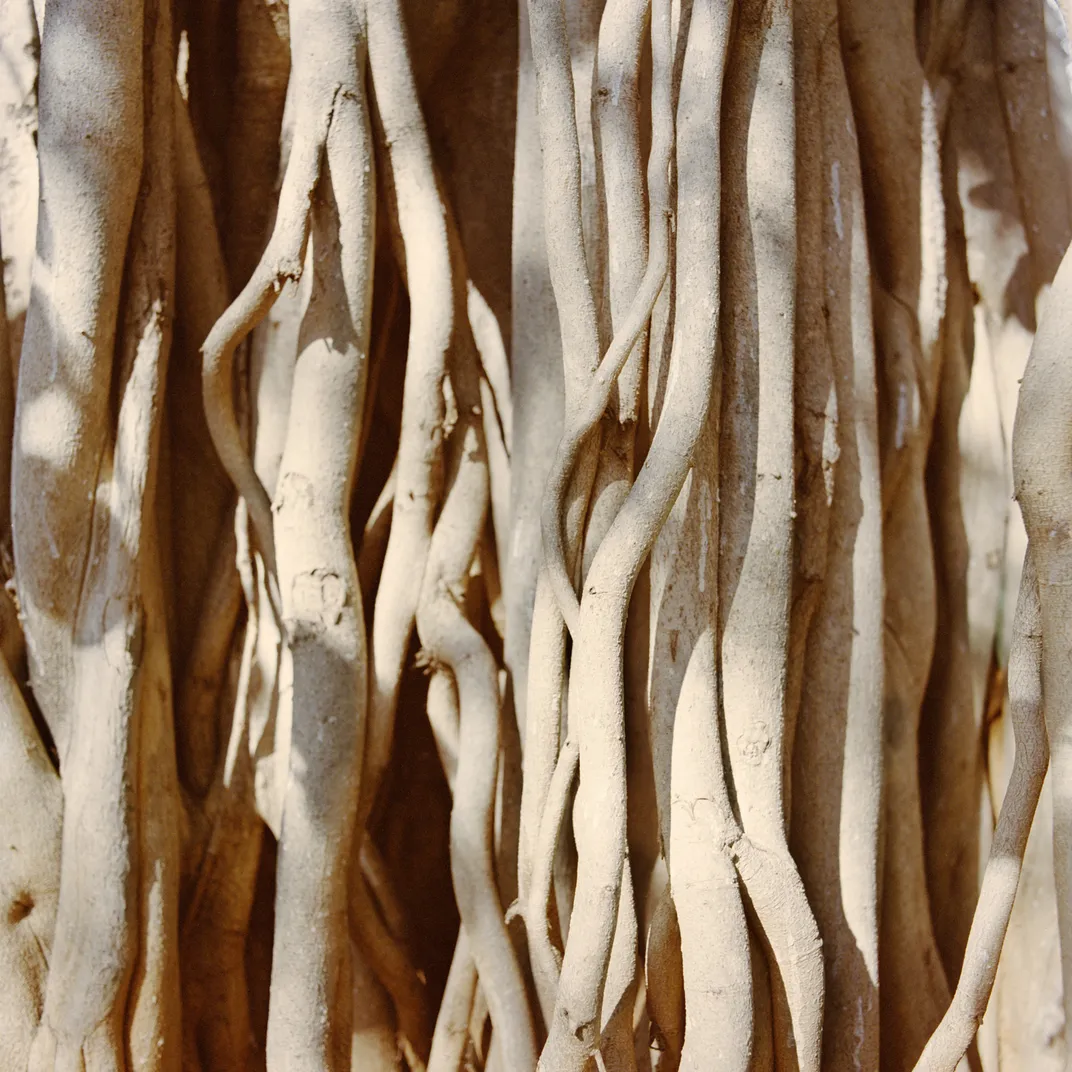

The banyan is a kind of strangler fig tree, and unlike most plants, which grow from the ground up, it thrives when it grows from the sky down. The seed catches in the branches of another tree and the young sprout dangles a braid of tender tendrils down to the forest floor. When that braid hits the soil, it takes root there, and the aboveground part thickens and hardens. The banyan becomes its host’s coffin: It winds around the original tree, growing branches that rob the host of sunlight. Its roots spread underground, depriving the host of nutrients and water. As the banyan grows, more “prop roots” descend from the branches to support the enormous canopy. Thimmamma Marrimanu is still expanding: It sits in an agricultural clearing, between two mountains in a patchwork of fields. That space has allowed it to keep growing until it looks like a forest unto itself. Over the years, Thimmamma Marrimanu has been damaged by cyclones, but it’s still remarkably healthy at more than 550 years old.

Its life expectancy is helped by the fact that the banyan is the national tree of India. People are reluctant to chop them down. The roots of the banyan are associated with Brahma the creator, the trunk with Vishnu the maintainer and the leaves with Shiva the destroyer. In the Bhagavad Gita, one of Hinduism’s most famous philosophical dialogues, an upside-down banyan is used as a metaphor for the material world. “Cut down this strong-rooted tree with the sharp ax of detachment,” Lord Krishna counsels. Throughout the country, people tie ribbons to banyan branches and tuck religious idols in the alcoves between their roots

Thimmamma Marrimanu has a legend of its own: Hindus believe the tree grew from the spot where a widow named Thimmamma threw herself on her husband’s funeral pyre in 1433. Because of her sacrifice, one of the poles supporting the pyre grew into a tree with mystical powers. Thimmamma Marrimanu is said to bless childless couples with fertility and curse anyone who removes its leaves. Even birds are said to revere the tree by not sleeping in its branches. The local forest department pays laborers to guide young prop roots into bamboo poles filled with manure and soil; they place granite plinths beneath heavy branches for extra support; and they water the tree with underground pipes. These efforts help the tree’s radius expand about half a foot per year.

It’s common in India to find smaller banyan trees in temple courtyards, but Thimmamma Marrimanu is so large that it contains a temple at its core. Every day during my stay, I watched pilgrims remove their shoes and follow a soft dirt pathway to a small yellow pavilion where the funeral pyre is said to have burned. An old couple reached for a low-hanging branch and rubbed its leaves on their faces. They rang a bell and touched a statue of a bull, while a shirtless monk chanted and waved a flame before a black stone idol of Thimmamma. Irreverent red-faced monkeys fornicated on the temple roof and patrolled the tree’s lower branches, while hundreds of flying foxes hung like overripe fruits in the canopy. There were also parrots, doves and beehives, as well as village dogs and lean reptilian chickens resting in the shade. Despite the animal abundance, Thimmamma Marrimanu was nowhere near capacity: The villagers said 20,000 people could stand together under the canopy.

The tree’s canopy encompassed the entire scene like a circus tent. Unlike the staid and perpendicular redwoods of California, the tallest trees on earth, Thimmamma Marrimanu is tied up in knots. Its nearly 4,000 prop roots create an impression not just of multiple trees but of multiple personalities. In some sections, there is something almost carnal in the way the roots and branches curl together. In others, there is torture in their twisting, as though they’ve been writhing over centuries. The tree’s curves make its stillness seem unstable: If you watch it long enough, you feel you might just see it squirm.

**********

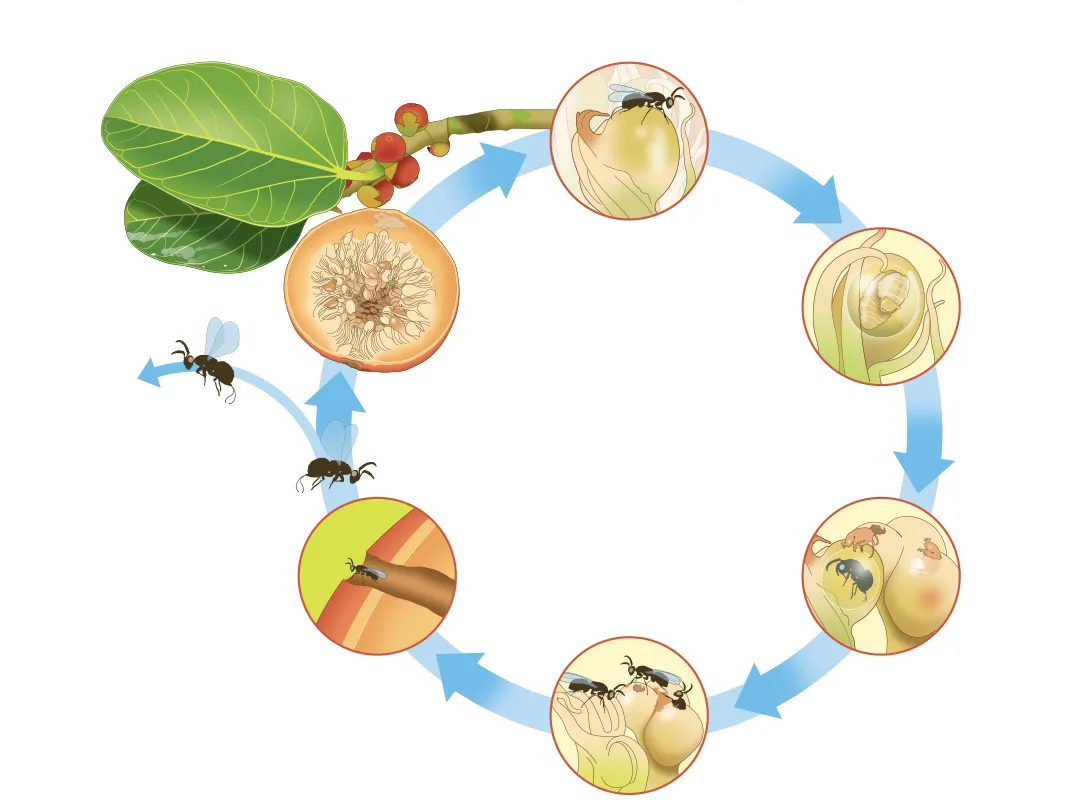

On the northern edge of Thimmamma Marrimanu, I found a cluster of round red figs. The fig is one of the most popular foodstuffs in the forest, and squirrels and black birds were foraging for them in the branches. The animal I sought, however, was in hiding. I picked a fig and split it with my finger. A brown wasp emerged, slightly stunned. The wasp had lived its entire life inside that fig. It was no bigger than a sesame seed, but the giant banyan would not exist without the tiny bug.

Evolution is usually represented as an orderly tree, but in reality its branches can become intertwined. Biologists call it “coevolution” when two species adapt to serve each other’s needs, and “obligate mutualism” when they need each other to survive. It’s hard to find a better example than the fig plant and the fig wasp.

A fig is not actually a fruit but a geode of inward-looking flowers. While other plants’ flowers offer up their pollen to all sorts of birds and bees, the fig sends out an aroma that attracts the female of its particular wasp species. The wasp then crawls through a tiny opening in the fig, where it lays its eggs and then dies.

Once those eggs hatch, and the larvae turn into wasps, they mate inside the fig and the females collect pollen from its internal flowers. The male wasps chew a tunnel to the fig’s surface, and the females crawl through it, departing to lay their eggs in other fig plants of the same species. Then the cycle begins anew.

Any given species of fig plant would go extinct without its pollinator, and a fig wasp would also disappear without its favorite figs. While this seems like an extreme vulnerability, it is, in fact, an amazingly efficient system of pollination. It has made fig plants (Ficus) the most diverse plant genus in the tropics. There are more than 800 fig species, and most have one main species of fig wasp. (The banyan’s fig wasp is called Eupristina masoni.) The faithful wasps can travel over great distances, bringing pollen from their birthplace to another tree far away. This allows fig trees to thrive in desolate places instead of clustering in forests. High above tropical forests, fig wasps are often the predominant form of insect life.

On my last day at Thimmamma Marrimanu, music woke me early. Sunbeams had lanced the darkness, and the flying foxes were returning to the tree to roost. I walked to the temple. Monkeys sat on the roof beside the speakers, while three workers swept the floor and brushed their teeth. It did not seem so important whether a funeral pyre once burned at this location or a banyan seed hatched in another tree. Thimmamma Marrimanu’s biology and mythology shared themes of death, love and sacrifice. Under its giant canopy, faith and science have grown together.

Related Reads

The Tree: A Natural History of What Trees Are, How They Live, and Why They Matter

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1510_Venice_Contrib_04.jpg)