Blues Alley

How Chicago became the blues capital of the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/blues-crowd_388.jpg)

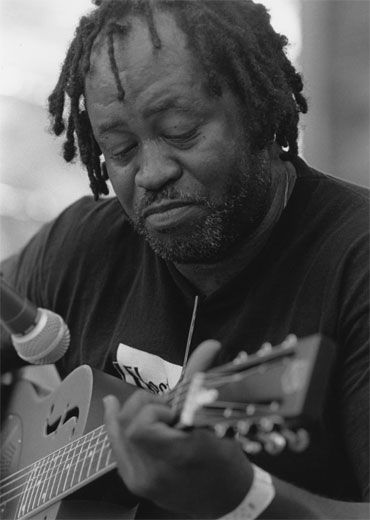

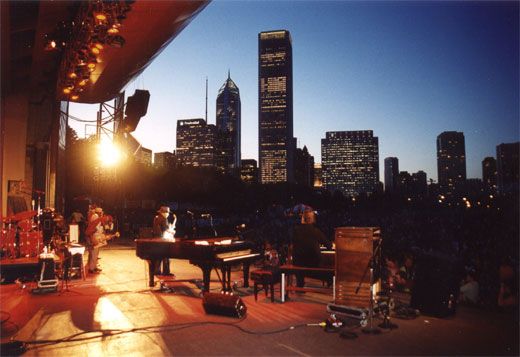

In June, Chicago will host its 24th annual blues festival—six stages, free admission—in Grant Park. Today Chicago is known as the "blues capital," but the story behind this distinction began some 90 years ago. In the early 1900s, Southern blacks began moving to Northern cities in what would become a decades-long massive migration. Chicago was a place of promise, intimately linked to recurrent themes in blues songs—hope for a better life, for opportunity, for a fair shake.

This year's festival honors piano player Sunnyland Slim, who died in 1995 and would have celebrated his 100th birthday. Giant in stature and voice, Sunnyland was a formidable personality on Chicago's blues scene, and his journey to the city somewhat parallels the history of the blues. Beginning around 1916, millions of African Americans migrated from the Mississippi Delta and other parts of the rural South to cities like Detroit and Chicago, where burgeoning industry and loss of workers to World War I promised jobs. For many, including musicians, Memphis was an important stop on this journey, and Sunnyland spent more than a decade there before moving to Chicago in the early 1940s.

When he arrived, blues players were starting to plug in their guitars. Work hollers and solo country blues were fusing with an edgier, fuller ensemble sound. Sunnyland became a staple on the scene with his boogie-woogie style and roaring vocals. "He had an unreconstructed down-home sound—very powerful, very propulsive, very percussive," says David Whiteis, long-time blues critic and author of the recent book Chicago Blues: Portraits and Stories. "He had that amazing voice—incredibly powerful voice." As Sunnyland played venues on the West Side and South Side, a raw, electric Chicago blues style began to gel.

The social aspect of live blues, particularly the interaction between performers and audiences, has always been essential. Yet the proliferation of venues hosting these social gatherings wasn't the only thing that made the Chicago's blues scene boom. The recording industry—Chess Records, Vee-Jay and numerous other small labels—was a huge force. Sunnyland recorded for Chess Records (then called Aristocrat Records) and eventually brought Delta transplant Muddy Waters into the Chess studio. Waters would come to exemplify the electric Chicago sound of the 1940s and 50s. At the time, much of the blues being played in Chicago was a slicker, jazzier, jump blues style. Waters brought a sort of "roots movement" to blues, says Whiteis, with his primitive, raw Delta sound that was at the same time urban. It was aggressive and electric, and it influenced a whole era of music. By the late 1940s, Chicago was a powerhouse for this "gutbucket" electric blues.

The blues scene had its own economy and cultural draw. "It welcomed [Southerners] into the city," says Chicago native and blues writer Sandra Pointer-Jones. "It gave them the go ahead to migrate here, because they knew that there were jobs here and they knew they had entertainment." To many of these Southerners, the city seemed less foreign because they recognized the names of musicians they knew back home. In the neighborhoods where blues clubs abounded, such as the South Side's Maxwell Street, newcomers spent their dollars at the grocery stores and on liquor at the clubs. Blues musicians frequented local hairdressers, tailor shops and clothing stores. Audience members sought out the stylish clothes performers wore on stage, contributing to the local market. This heyday cemented Chicago's title as a "blues capital" and continued through the early 1960s. "At one time Chicago was known as having the best blues musicians in the country," says Pointer-Jones. "Everybody who was anybody was in Chicago, came from Chicago, or went to Chicago."

Beginning in the late 1960s and into the 70s, however, blues began losing popularity with black audiences. While some critics have attributed this to upper classes shunning "poor people's music," Pointer-Jones thinks it became overshadowed by soul, R&B and 1970s disco. Yet during the same period, the blues began attracting a larger white audience, including rocker musicians and folk "revivalists." A new collection of clubs on the North Side opened, catering to this interest.

Today, some of the primarily black neighborhoods that once fostered blues music, such as on the South Side, have changed, and residents have been pushed out by gentrification. Maxwell Street, known for its street market and blues street musicians, has been swallowed up by the University of Illinois. And although white people have become regulars at clubs in typically black neighborhoods, the reverse is not happening, says Pointer-Jones. "More African Americans are not going to the North Side clubs."

The result is what some might call an unhealthy blues scene: Alligator Records, which began in 1971 and has become a top national blues label, is the only big record company left. Local blues radio programming—which thrived during the blues heyday—is slim to nonexistent. Big-name veterans aside, Chicago musicians are not as well-known as they used to be.

Still, the scene remains alive, from the North Side's traditional Chicago blues to the South Side's blues melded with contemporary soul music. The blues fest, which began in 1984, brought more people to clubs on all sides of town. The West Side soul-food restaurant Wallace's Catfish Corner puts on outdoor blues shows in the summer. The famous South Side jazz and blues club, the Checkerboard Lounge, reopened in a new location near Hyde Park. North Side clubs established in the 1970s are still active, including B.L.U.E.S. and Kingston Mines. Rosa's Lounge on the near West Side offers classes on blues history and was the first sponsor of the Chicago Blues Tour, which takes people to historic spots and blues venues. Buddy Guy's Legends club in the South Loop hosts local and national acts, but will be relocating sometime this summer. Lee's Unleaded Blues on the South Side is a neighborhood mainstay.

Regardless of club geography, Guy, Koko Taylor, Billy Branch, Sharon Lewis, Cicero Blake, Carl Weathersby, Deitra Farr, Billy Branch, Denise LaSalle and many others are all regularly on stage. And the survival of blues music, it seems, has to do with stretching the definition a bit. "Sometimes I think the worst thing that ever happened to the blues was the word 'blues,'" says Whiteis. Indeed the resilience of blues in Chicago has less to do with the music's physical form than with its expression. What's important is the socializing and the stories—about journeys, emotional struggle and disenfranchisement—and the musical style that delivers these stories can vary. Blueswoman Sharon Lewis's band often performs Kanye West's recent hit "Golddigger," older tunes by Sam Cooke and Chuck Berry and funk and gospel songs. Patrons at Wallace's Catfish Corner might hear anything from R. Kelly to The Temptations. Today young musicians like Keb Mo, Guy Davis, Corey Harris and Josh White, Jr. are revisiting more traditional blues forms, but Whiteis claims that more contemporary black music—the neo-soul songs of Mary J. Blige or Erykah Badu, for example—could also be considered blues.

Blues music—in all its derivations—is still active in Chicago, and it plays a significant role in the city's identity and self-promotion. With vast chapters of American music history under its belt, Chicago remains a place where blues can ferment and find a substantial, passionate audience. As Pointer-Jones says, "Blues in the beginning was not just a genre, but it was a culture."

Katy June-Friesen has written about the history of girl groups for Smithsonian.com.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.