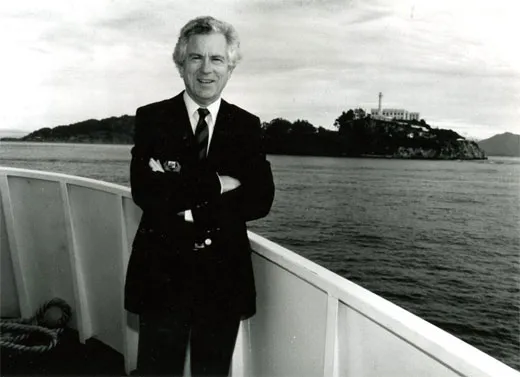

Breaking into Alcatraz

A former guard’s inside look at America’s most famous prison

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/alcatraz-631.jpg)

Frank Heaney can't escape Alcatraz. In 1948, then just 21 years old, Heaney became the infamous federal prison's youngest guard ever. He later went back as a tour guide and still visits once a month to talk to people and autograph his book, Inside the Walls of Alcatraz. Which is where he takes us now.

What made you want to be a prison guard?

I was born and raised in Berkeley, and from there you can see Alcatraz. In fact, there's a street in Berkeley called Alcatraz, and all the way down Alcatraz Street you can see Alcatraz.

I had a high interest in prisons because I had a cousin who worked in Folsom. I was in the service during World War II for a while, got out in '46 and was going to college in Berkeley. I was in the post office during a lunch break, and the post office had civil service postings. One said, "Correctional officer wanted on Alcatraz." They really emphasized during training class that there are no guards on Alcatraz, only correctional officers. They were always worried about their image.

What was a typical day for a guard, er, correctional officer?

It was a regular 40-hour week, 8-hour day. Three shifts. Somebody had to be there all the time. I went to training class for about a month. They teach you procedures, weapons training, jujitsu, how you should act. The different jobs were doing the counts, doing shakedown detail, going through cells, checking to see if there was any contraband, being a yard officer. Things like that.

Did you have to be a certain size and strength?

You didn't have to be a great big guy. You had to be big enough to take guys down. Just a normal man.

What was a typical day like for a prisoner?

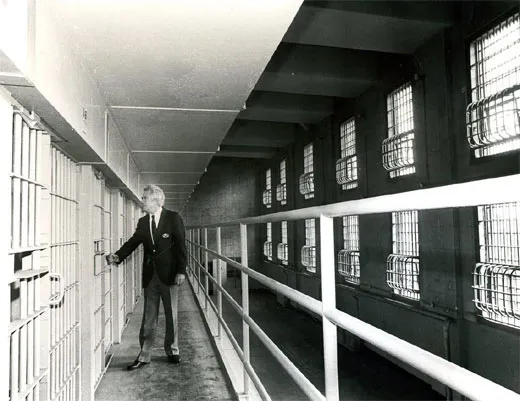

Monday through Friday, we'd wake them up at 6:30 in the morning, and they'd have a half hour to get themselves dressed. Before that, we did a count. They had to stand in front of their cell, and we'd walk by and count them. As soon as that count was over, the lieutenant would blow a whistle, and by each tier on either side they would file into the dining room for breakfast, which was called Times Square.

There was no talking, before I was there, except on weekends in the yard. But that's a very hard rule to enforce. It lasted a few years. They call that the silent system. That ended and went into the quiet system. They could talk low or whisper, but not holler.

After breakfast they'd get ready to go to work. They had 15 minutes in their cells to put on a jacket. Alcatraz, particularly in the morning, was usually cold. They'd stand by the door and we'd make a quick count again, blow the whistle, then file out the same way out the door into the exercise yard. Then we'd count them down in the yard again. So from the yard they'd go downstairs to the prison industries, which consisted of a large military armory. Once down there, the officer in charge of the shop would make a count himself. They were always fearful of an escape.

They were down there till about a quarter to 12. Then they'd file back up, same routine, into the yard, into their cells to change. Then they were counted again and would go into the dining room for lunch. At one, they would then file back down again to go to work. At 4:30, quarter to 5, they'd go in for dinner. Then we'd lock them up, and that's their last lock-down. Until 9:30 they could read. After 9:30, no lights.

Where did the prisoners come from?

Alcatraz is in California, but it's a federal prison. There were inmates from all over the United States. Inmates were all sent there from other federal penitentiaries, not from courts. A warden might say, "If I see you one more time, you're going to Alcatraz."

What could they have in their cells?

They were issued a razor. The blades we'd keep. It was a typical double-edge, Gillette-type razor. Soap. Tooth powder. A toothbrush. Then they were allowed a limited amount of books. We had a library. When they wanted a book, they'd write it on a chip, put that chip into a box on the way to the dining room with their cell number and the book that they wanted.

No newspapers. No magazines. No tailor-made cigarettes. Only roll-your-owns. Bull Durham type. They were allowed a cheap corncob pipe with George Washington pipe tobacco—the cheapest one the government could buy. They smoked quite a bit inside their cells. That place was loaded with smoke. I'd say 80 to 90 percent of the prisoners smoked. At Christmas time, they'd give them about six packs of Wings cigarettes. They had to be smoked by the end of the year. After that, it was contraband.

Were weekends any different?

On weekends, there was no real work. They stayed inside their cell for a while after breakfast. Then they went out in the yard where they played handball against the concrete wall. They had a softball diamond. Except if you knocked the ball over the wall, you were out, and couldn't go over the side to get it.

Young guys liked it, but the old guys hated it because you always had to keep your eye open or you'd get whacked with one of those balls. No more than three guys together or we'd break it up. We didn't want too many guys talking together. They played cards, were only allowed to play bridge. But they didn't play with cards—those can wear out or blow away. We gave them dominoes.

Were there a lot of fights?

There were fights, but there was more knifings. You can't fight somebody and we won't see it. But if you got really angry at somebody, you'd plot to knife him. They'd have a homemade shiv made out of wood. When they were out in the yard, you'd have some friends surround the guy, and you'd stick him. A piece of wood could get by our metal detector.

After you stuck him, you'd all walk away and leave the shiv down on the ground. When you asked around, of course, no one had seen it. But you could have a snitch who would tell a lieutenant so maybe he'd get a privilege unknown to other inmates. But you could imagine what happened if they found out who the snitch was.

Did they have visitation rights?

The inmates were allowed one visit a month, by a blood relation. Officers had to find out who they were, had to be a close relative or, if you didn't have that, maybe a close friend. They were allowed to talk for an hour. It kinda went by our boat schedule. There was no talking about what's going on in the outside world. Just family business.

Before my time, they said Al Capone's mother came over with his wife, Mae. They went through the metal detector, and apparently Mrs. Capone kept setting it off. They had a woman go into the dressing room with her and found out she had metal stays in her corset.

Did anyone try to escape?

There were a total of 36 inmates and 14 tries to escape from Alcatraz. No serious attempts during my time. The best known was made famous by Clint Eastwood [in the movie Escape From Alcatraz]. But there were others. The bloodiest one was in 1946, six inmates including Clarence Carnes, who I knew. He was the youngest inmate there, a full-blooded Choctaw Indian. They spread the bars apart, and this guy starved himself to fit through. He knocked out the officer and dropped his weapon, a .45 automatic, to his mates down below. They took over the cell house, held it for two-and-a-half days.

During that time, all but three inmates got killed. Those three got captured. Two were sent to San Quentin and were gassed. I'd just started work then, in 1948. The other guy got two life sentences plus 99 years. Clarence was a young guy who got talked into the escape attempt. He finally got out, and I was with him in the 80s on the Merv Griffin Show, on Mike Douglas and a number of other shows. Him as the youngest inmate, me as the youngest guard.

As the youngest guard ever, did you get picked on?

That was my big problem. I was 21, and they would try to take advantage of my age. I just had to overlook it. They'd give me the finger. I knew if I called them on it, they'd say, "Oh, I was just scratching my nose." They'd blow kisses at me. How can you tell on that? The administration would have said, we made a mistake hiring you. I ignored it, and that was the best way.

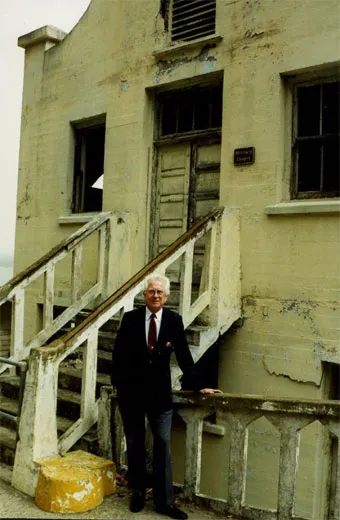

There was also the doom-and-gloom despair, the despondency that prevailed in the place. I was more sensitive to it. I left during the Korean War—that was my escape from Alcatraz.

You knew the Birdman of Alcatraz, Robert Stroud. (Stroud raised canaries in his cell at Leavenworth prison and was the subject of the 1962 film, Birdman of Alcatraz.)

I knew him in the hospital. He was developing Bright's disease, a kidney condition, and needed further medical treatment. They put him into a special room—it wasn't a cell, it was a small room for utilities, but they made it into a cell so he could be by himself. The only contact he had was with people like myself, working in there. They did watch him closer than other inmates. A few times I was in there by myself, and I was warned—he stabbed an officer to death at Leavenworth.

Did you know any other interesting characters?

There was this one guy, George "Machine-Gun" Kelly, that everybody liked. He was a banker, a bootlegger, a kidnapper. He had a very good personality. A very affable Irishman. Unlike any inmate I knew there, he had a couple years of college and came from a pretty good family in Memphis, Tennessee. He was a typical case that got caught up during the Prohibition period. When that ended, he was already in it. You turn out to be what you're hanging around with. As far as I know, he never shot anybody. The movies show he did, but movies are the worst way to get any kind of truth.

So I take it you didn't like The Shawshank Redemption.

It was so ridiculous. Remember when the captain beats the guy to death in front of all those guys? I'm saying, come on now, this is a state prison in New England getting away with this stuff.

The worst movie, and my name is in the credits, is Murder in the First. I worked with Kevin Bacon. It's so ridiculous, it almost made me throw up. People thought it was so real. We were constantly beating them in that movie. The way I remember it, it was just a bunch of guys trying to do a job.

And Birdman of Alcatraz?

The portrayal by Burt Lancaster—I got mad at the movie because it sympathetically showed Stroud. But after seeing it a few more times, I liked it. I just disregarded the truth, then I enjoyed it.

In Shawshank, one inmate had a hard time leaving because he was so used to the conditions inside. Did you find that to be the case?

That's not an exaggeration, that's true. One inmate who was there for 15 years, going on beyond that, he was getting ready to be released. He was so nervous. Some of these guys could con a doctor into giving them sleeping pills. They gave him some sleeping pills. He was highly nervous about getting out. He didn't know how he'd be.

Is it true that everyone inside thinks he's innocent?

Yes, to a certain extent. I don't know whether they conned themselves into thinking they were innocent. Alcatraz was unique, because those suckers have so many raps against them. Some of them did try to convince me.

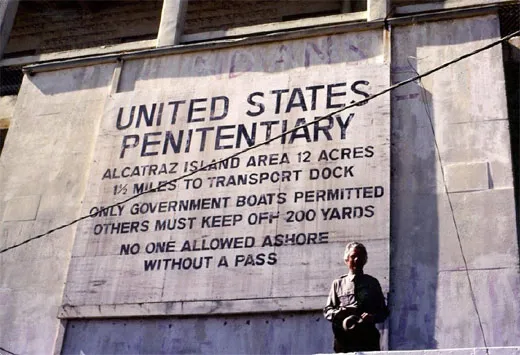

What is it about Alcatraz that the public finds so fascinating?

Where could you find a place that has so much notoriety? This is starting way back when it began with Al Capone being one of our first inmates, in August 1934. It's in the middle of the bay; at nighttime, when it's foggy, you see the lighthouse going around. All that conjures up, what's going on is so mysterious, and it was kept that way deliberately. All the mystery that surrounded it. If it was a prison on land, I don't think it'd have half the mystique it has.

It caught the public's imagination. We will be dead and gone for years, and people will still be saying, coming off the boat: "That's Alcatraz."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)