Breeding the Perfect Bull

A Texas cattleman used genetic science to breed his masterpiece – a near-perfect Red Angus bull. Then nature took its course

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Best-Bull-RA-Brown-Ranch-631.jpg)

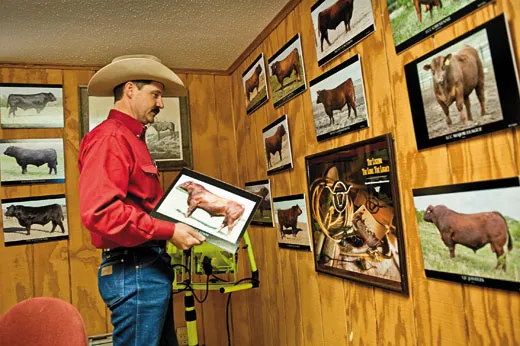

There once was a bull, an astonishing bull with a handsome, wide muzzle, stunning scrotal circumference and a square frame solid as a sycamore. He was the son of Cherokee Canyon, the grandson of Make My Day—a noble pedigree. The cowboy who designed him, who chose the semen, selected the dam, prepared and inseminated the uterus, named him Revelation. “We don’t intend to present this bull as divine,” the cowboy, Donnell Brown, would write in his 2005 sale catalog, “but we do count it a blessing to have raised him.” Brown was a salesman by nature, but not given to hyperbole. He believed in his heart that Revelation, at just a year-and-a-half old, could become the most storied bull in the history of the Red Angus breed. Finally, after decades of tinkering: might this be the masterpiece?

Every October, cattle buyers from all over the United States gather near Throckmorton, in north-central Texas, where the R.A. Brown Ranch has been selling breeding cattle for more than a century, and where as many as 800 head will go at auction in a single day. Fathers, sons, grandsons—the ranch has passed through five generations. Donnell Brown, 41, is the current cowboy in charge, and at the 2005 R. A. Brown Ranch Bull & Female Sale he sold Revelation to a Houston businessman with a weekend ranch for $12,000.

In time, the bull could turn out to be worth much more. Top breeding bulls—once they’re proven to produce prime calves—can sell for more than $100,000. In the breeding business, the buyer gets the animal, but the seller typically retains an interest in the genetics. Donnell kept the rights to half of Revelation’s semen. It would be two years before anyone would know the quality of the bull’s progeny.

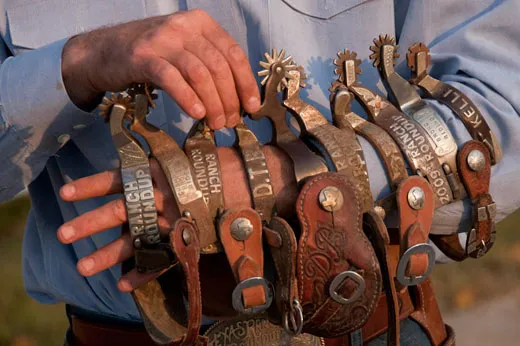

Donnell wears creased Wranglers, a starched plaid shirt with long sleeves and a white hat with the brim cupped obediently up—not in some floppy, haphazard shape like East Texas cowboys wear. The spurs on his boots bear his initials, but he does not wear jingle bobs on them, those dangling silver baubles you see on flashy Arizona cowboys. No, cowboys in Throckmorton consider themselves West Texas cowboys: starched and ironed, just the way cowboys are supposed to be. Donnell is tall, slim, with a quarterback’s build and the deep blue determined eyes of a man who is hanging on with all his might for the ride. No giving up on the four life goals he set for himself at age 23: get to heaven; be the best possible husband and father; be healthy and happy; produce the most efficient beef cattle in the entire world by converting God’s forage into safe, nutritious, delicious food for His people. He wears a clean, straight mustache above an intelligent smile.

Two years after he sold Revelation, Donnell’s dream came true: the bull’s babies were at the top of the class. The weekend rancher from Houston didn’t quite know what he had, so Donnell called him to explain.

“A superstar,” Donnell told him, pointing out, as he often has to do, that a bull in today’s marketplace is like a player in the NFL draft, except with a longer roster of stats. He told him that Revelation’s progeny were showing beef marbling scores that were off the charts, along with breathtaking rib-eye areas. Producing a bull whose offspring have even one of these super stats is like hitting the lottery. But two? A near miracle.

“You should syndicate Revelation,” Donnell advised, offering to bring the bull back to the R. A. Brown Ranch, where it would enjoy higher visibility, the conditioning of an athlete and Donnell’s help in selling shares to investors. Word spread fast. Donnell and the rancher sold seven shares of Revelation for $1,650 apiece and had 14 more ranchers ready to pony up.

So of course Donnell felt blessed. Of course he was feeling something resembling pride when he went out on a routine cattle call one warm October morning in 2007 and looked around the east holding pasture.

“Come on, bulls!” Donnell cried. He sprinkled sweet grain on the brittle prairie grass, and the bulls gathered like children after the big piñata spill. All of them but one. “Come on, bull! Come on, buddy!” Donnell called to the slacker lying some 20 yards distant. It was Revelation. “Hey!” He went closer, and closer still. “Come on, buddy!”

Revelation lifted its head but otherwise remained as inert as a lump of clay. The bull could not get up. Donnell bent over to find that its right rear leg had been mangled, most likely in a fight with another bull, a battle for turf or just a boyish tussle for fun. Revelation was crippled, and a crippled bull is worthless. A crippled bull produces less and weaker sperm. A crippled bull is sent straight to the packinghouse.

“No,” Donnell said. “Please God, no.”

The average American at the backyard grill who cares to think about the steak sizzling before him may imagine little beyond the packinghouse, where meat is cut and shrink-wrapped, or perhaps the feedlot, where beef cattle fatten up on corn on their way to market. But those are only two stops—relatively short and highly industrialized stops—in a long process. Before they get to the feedlot, cattle live the lives their bodies were built for: grazing beside their mothers on endless pastures at ranches called “cow-calf operations.” These are independent ranches, about 750,000 of them in the United States, most of them with fewer than 50 head. The R. A. Brown Ranch, which has 2,000-odd head, belongs to a subset of these ranches that specialize in breeding: the “seed-stock providers.” They begin the beef production chain. The cowboys who run them are the inventors, the tinkerers who choose the genetics that determine the qualities of America’s tenderloin, rib eye, sirloin, filet mignon and burgers.

April marks the earliest days in a commercial cow’s life, and arguably the happiest. The calves at the R. A. Brown Ranch, just 6 to 8 weeks old, have been tagged and vaccinated, and now wander freely, chewing the wild grasses of Texas. The sunrise is so red it fills the sky with stripes of fire and turns the cowboy hats pink. Jeff Bezner, a 29-year-old cowboy with prematurely salt-and-pepper hair, glasses and an air of sparkling innocence, has the back of this cattle drive, while two other cowboys take the flanks. They keep the cattle in a clump, pushing them from pasture to paddock. Herding cows is not difficult, especially Red Angus, famously gentle and polite. (For a good time, try wrestling up some Brahmans.) The cows thunder obediently through the buffalo grass as the cowboys’ horses amble and the men occasionally wave their arms, letting out a “Wheeet, wheeeet,” or “Get on now, gals!”

“I never said nothing about love,” Jeff says to his team, referring to the love he has, in fact, been talking about all morning. (Jeff wants a wife.) A cowboy on a cattle drive has time to ponder such matters.

“You’ve known her for a whole six days!” one shoots back.

“Eight,” Jeff says, slapping his chaps. “I’m telling you, she’s awesome.” He whistles through his teeth. The cattle move as one, a rumbling blanket of rolling amber, humming their lazy cow songs: aaaroooom, aaaroooom, aaaroooom.

Beef, even now, is still personal, is cultural, is cowboys.

It isn’t like pork or poultry. Commercial pigs and chickens live their whole lives in industrial-size barns. Beef, in its beginning stages, will never be produced that way because a simple fact remains: all cows eat grass. You need land to grow calves. Lots and lots of land. That land is divided among many owners. Beef production is unlike any other agricultural industry in that it has remained utterly dependent on the family farm or the extended-family farm, manned by the same people who sing in the church choirs and run the school boards and football leagues that knit the fabric of small towns like Throckmorton. Beef production is the largest single segment of American agriculture, a $76 billion industry, and yet more than 97 percent of U.S. cattle ranches are family-owned and -operated.

The average American eats 62 pounds of beef a year, or almost three ounces a day, and shows no sign of slowing down; as a group, Americans regularly consume more than 27 billion pounds a year. This is, in part, a function of food science and the seed-stock providers: beef keeps getting tastier.

Beef is simultaneously low and high tech. Past necessarily coexisting with future. Because of the cowboys and because of the human desire for better meat.

To create the finest steaks, there really is nothing as important as a fabulous cow. Except, of course, an amazing bull.

On the day he found Revelation crippled in the east holding pasture, Donnell stood there feeling sick. Gut-sick, like a man watching his house burn down. In the silver liquid-nitrogen tank up in the ranch’s artificial insemination center, he had only about 100 “straws,” or doses, of Revelation’s semen—hardly a gold mine.

He took his cellphone off his belt clip and called his wife, Kelli, back at headquarters.

“Oh, Donnell,” Kelli said, desolated. She told Betsy, Donnell’s sister, who works in the office, too, and soon word passed around the family.

All three of Donnell’s siblings, and their spouses, share ownership of the ranch with him and Kelli. She serves as marketing maven and quiet, sturdy voice of wisdom—and as president of the Red Angus Association of America. Ranch headquarters is the small red house where Donnell grew up and now lives with Kelli and their two teenage boys, Tucker and Lanham.

In the end, Donnell decided no, he would not give up on Revelation. He would try to save his masterpiece. So he hauled the bull away in a trailer and drove five hours to a veterinary hospital near Austin, where he learned that Revelation had torn two ligaments, the anterior cruciate and medial collateral, in its right rear knee. “Nothing we can do for him here,” the vet said, pointing Donnell to specialists at Kansas State University, 11 hours away. So Donnell got in the truck and drove. Revelation was like Barbaro, the racehorse. If ever there was an animal worth going the extra mile for, it was Revelation.

“We can try to construct a new knee,” the Kansas vet said, with only vague encouragement in his voice. “Sure, we can try.”

Donnell’s parents, Rob and Peggy, used to live in the red ranch house, but in 1998 they retired to the fancy house in town with the big columns out front, just as Rob’s parents had done before them. Before she married Rob, Peggy’s name was Peggy Donnell, and that’s how Donnell got his name.

Rob, now 74, is himself legendary in the beef world; he played a vital role in determining the kind of steak America now eats. He came of age when the Hereford was the cattle of choice for the U.S. beef industry—a reliable, thrifty breed with far more muscle than the Texas Longhorn, its predecessor as America’s main beef cow.

At Texas Tech, Rob had learned of a brave new world. “Continental breeds!” he said to his father, R. A., after he came home with his degree in agriculture in 1958. Breed a Hereford with, say, a Brown Swiss and get a larger carcass with, perhaps, the same quality meat—or better! Rob had other ideas, other breeds, other dreams. R.A., a man of tradition, would have none of it. Not until 1965 did he give Rob his reluctant blessing to crossbreed; within days, he died of a heart attack. If he hadn’t given his assent, the ranch never would have enjoyed its explosive success in creating better and better meat.

Rob crossed a Hereford with a Brown Swiss and sure enough, he got cattle fully 100 pounds heavier at weaning, with the same hardiness as a Hereford. “Brilliant!” he thought. But the market did not quite agree. The cattle were not uniform in color, like the good old-fashioned amber Herefords. Some were brindle and some were gray. Coat color has nothing whatsoever to do with carcass quality, but even so, Rob’s cattle were discounted at auction because they looked funny.

So Rob got back to work. He mixed his Herefords with Simmental, a different Swiss breed, and that solved the color problem. To that hybrid he added Simbrah, a Simmental-Brahman mix, to create cattle with heat tolerance. He added Red Angus for marbling. He got a planeload of Senepol from the Virgin Islands to add a gentle demeanor. And by 1989 he had a hybrid called the Hotlander, which is still popular among some breeding connoisseurs.

By then Rob’s son, Donnell, was at Texas Tech, studying genetics. It’s the Throckmorton way, after you grow up cowboying and playing football for the Throckmorton High Greyhounds (2005 state six-man champions!).

When he came home with his degree in 1993, Donnell said, “Dad, it’s better to be on the leading edge than the bleeding edge.” His father may have been ahead of his time, Donnell thought. He was creating superior beef, absolutely, but not necessarily beef the marketplace understood. Donnell brought science back from Texas Tech, but he also brought marketing.

Never a place for subtleties, the market understood one thing: Angus. Over the past quarter-century, brilliant marketing by the American Angus Association has made the word “Angus” synonymous with “best steak in the world.” Specifically Black Angus, even though Red and Black Angus carcasses are indistinguishable without the hide. But the American Angus Association promoted black, and so in today’s market, solid black cattle, for reasons almost entirely psychological, bring top dollar.

“We have to create the meat that people want to buy!” was, and remains, Donnell’s main point. Rob agrees, of course, but on the other hand he has the soul of an inventor and can’t stop thinking of awesome new things to try. The father is the boy in this relationship. Donnell: buttoned-up, doing the right thing, selling it with a smile. Rob: trial and error and joy.

The R. A. Brown Ranch still offers its Hotlander composite, but Donnell directed the business toward an Angus focus, with a twist: become the premier Red Angus breeder, and have the genetics to prove it.

And he had those genetics in Revelation. He had them.

The vets worked on Revelation’s leg for a year and a half. Surgery and rehab, surgery and rehab, and more surgery. Finally, in August 2008, the vet shook his head no.

“OK, then,” Donnell said. “OK.”

“It was like a close friend dying of cancer,” he says today. “You’re almost relieved when it’s over. Almost.”

He did not say goodbye. He sent Revelation to the packinghouse, where the prize bull became 1,200 pounds of hamburger. Sometimes, Donnell says, he wishes he could have saved Revelation’s head like a deer’s and mounted it. Sometimes he does think that way.

But mostly he thinks about Revelation’s ear. He saved a notch from Revelation’s left ear. He sent it to the ViaGen cloning lab in Austin. And there it sits, on ice.

To achieve uniformity, and to maintain quality control, Donnell likes all his cows to be on the same estrus cycle. That’s why, in April and May, during breeding season, a lot of them wear seeders—vaginal plugs carrying progesterone, each with a blue string for easy removal in a few days. The progesterone keeps the cows from coming into heat. When the plugs come out, each cow gets a shot of prostaglandin, which ultimately results in ovulation. At that point, one of the cowboys puts on an arm-length plastic glove and inserts an artificial insemination syringe loaded with 20 million sperm cells. George Self, who has cowboyed at the R. A. Brown Ranch for 57 years, is by far the best at this. “He has a gift with his hands to know how to feel into a cow that most people don’t have,” Donnell says. George will feel the reproductive tract with one arm, then with the other hand, guide the syringe through the cervical rings (the tricky part) and deposit the semen at the opening of the cervix. It takes maybe 60 seconds per cow, and every cow on the ranch, 1,300 in all, is bred that way, as many as 400 in a single day.

The finest cows, the genetically superior ones, are put on a different regimen. AbiGrace is the Browns’—and the breed’s—rock star in this category. She will be overstimulated for maximum egg production and inseminated with choice sperm. The resulting embryos, as many as a dozen, will be flushed and frozen. Donnell could sell those embryos for more than $1,000 a pop on the Internet if he chose, but usually they are inserted into surrogate cows—proven dams that don’t, let’s say, have the genetics to be worth breeding. AbiGrace can then be stimulated to make more embryos, and more still.

Without scientific assistance, a mature cow will produce one calf a year; with embryo transfer, AbiGrace can crank out 25.

Cloning Revelation is a big decision, and Donnell does not know what to do. He has never cloned a bull before, never imagined himself stuck in the mud of such profound uncertainty. For about $20,000, an exact genetic replica of Revelation could be engineered in the lab and soon enough be out there grazing on the silver bluestem. Actually, technically, Donnell could order up two new Revelations, or 20 Revelations, or more. But: “There’s the question of playing God,” he says, “and there’s also just the business model to consider. Like I tell my dad, it’s better to be on the leading edge than the bleeding edge.”

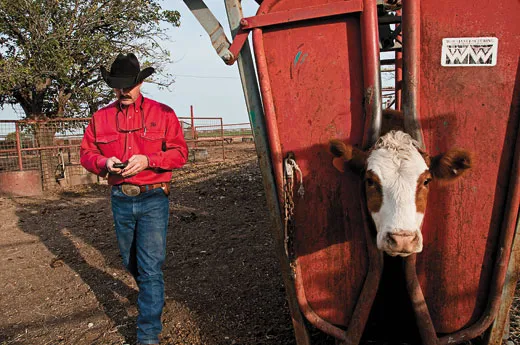

Donnell stares at the horizon a lot; he spends all day in his truck, so many days in his truck, covering hundreds of miles a day sometimes to look at bulls or pick up cows. On this April afternoon he’s just returning from a ranch in Coleman, Texas, where he transferred 70 valuable Red Angus embryos into some surrogates. He’s headed down to his ranch’s artificial insemination center to check on the action there.

He parks. He notices a splotch of dried mud on his starched jeans. He takes out a knife he keeps clipped to his belt, unfolds it and scrapes that mud right off.

The artificial insemination (AI) center is a modest white tin barn surrounded by a catacomb of pens and clanking red gates. It’s at the far end of the ranch, flanked by shady hills providing cool comfort to hundreds of cattle. Atop the hill, a lone oil derrick bounces its lunatic head up and down.

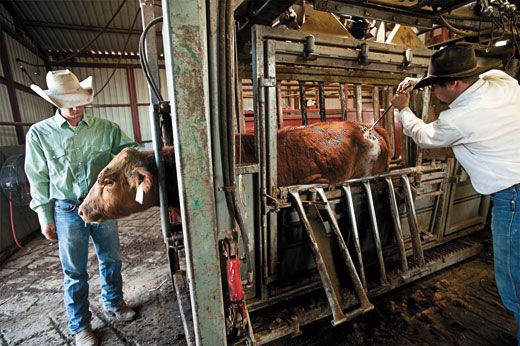

Inside the AI center, the main event is the mighty gray metal chute, a monstrous contraption that can, with the benefit of hydraulics, hold a cow or a bull in place. Then a cowboy can do what he needs to do: inseminate, castrate, brand, palpate.

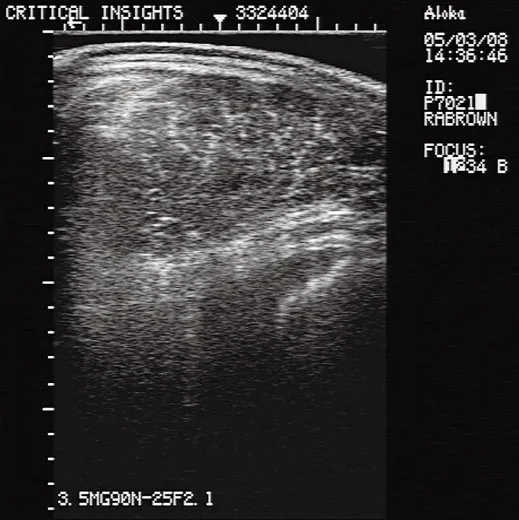

Today, a freelance cowboy who specializes in ultrasound technology is here with his machine, which is connected to a computer, which is connected to a thumb drive, which contains information that will eventually be uploaded to a lab in Iowa. Technicians there will run a program to translate the images into numbers.

“Howdy, sir!” Donnell says, all smiles.

“How’s your boy?” the cowboy says. “He’s playing ball next year?”

“You spying for another team?” Donnell says with a laugh. “Yes sir, Tucker’s looking to play quarterback. We’re proud of him, mighty proud of him.”

“I’m about through with these bulls,” the cowboy says, holding on to a humming electric shaver. “About a half-dozen left. Seeing some good scores.” He’s shaving some hair from the back of a 926-pound young bull. He squirts a shot of lubricant on the hide, then gently places his ultrasound wand over a spot between the 12th and 13th ribs. The image that emerges on his computer screen is unmistakably and perhaps unsettlingly a rib-eye steak. Clear as on a plate.

“Nice marbling,” Donnell says. “OK, real nice.”

The cowboy then gets a shot of the bull’s back fat. All carcasses are trimmed to the industry standard of a quarter-inch of body fat, so you’re hoping to see that score low, and marbling high. The complete examination takes less than five minutes, and when the ultrasound cowboy is through he pulls a lever, releasing the bull. The bull roars out while another thunders into the chute with a great clank and clatter.

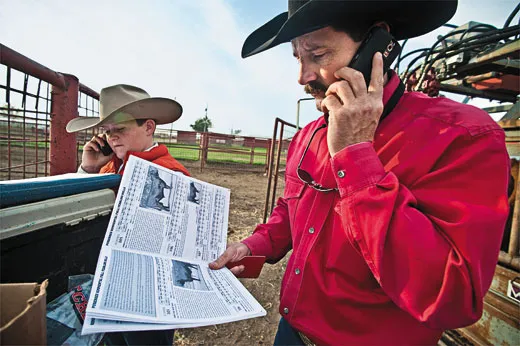

Once processed into numbers, the data will go to the Red Angus Association of America, where a cowboy like Donnell can pull them up on his Blackberry: the Expected Progeny Differences (EPDs) of one bull versus another and one cow versus another. A herd’s full set of EPDs reads like endless pages of Nasdaq offerings, a chart of numbers expressing the relative values of carcass weight, marbling, rib-eye area, fat thickness, maternal milk, cow energy value, calving ease, birth weight, weaning weight, yearling weight—14 traits in all—that each animal’s progeny has been statistically predicted to achieve.

EPDs can be difficult for the weekend rancher to master, but for a modern seed-stock provider like Donnell the information is gold. Get a dam with the best EPDs for calving ease and cow energy value, and breed it with a bull with the best EPDs for marbling and rib-eye area and maybe weaning weight times yearling weight (an online EPD Mating Calculator can help with this task), and see if you can’t just produce perfection. Tweak with the next generation, and try again, and again.

And then one day you find you have created something no cowboy has ever created before. Of course you name it Revelation. And of course, when it gets crippled, you do everything in your power to save it. And of course if you lose the battle and have to send it to slaughter you...clone it. Really? Really?

To date, no more than a thousand cattle have been successfully cloned in the United States, and market reaction has been mixed. People aren’t sure they want to eat cloned beef.

But still. It’s...Revelation! It’s Donnell’s masterpiece. Of course, to clone the bull he would need the approval of all seven ranchers who own shares in the syndicate.

Late one summer night, Donnell sits at his computer, and he types an e-mail to them, and he reads it over to make sure it sounds right. He pauses awhile. Nothing to lose by just putting the question out there, right? Nothing to lose.

And now it is October, and a beautifully wet one at that. Throckmorton averages just 26 inches of rain a year, and so drought is a constant concern; all this precipitation feels like a blessing, greening fields of wheat and refilling water holes. The 2009 R. A. Brown Ranch Bull & Female Sale is just a few weeks away. The leadoff bull is Turbo, son of Destination, great-grandson of Cherokee Canyon, great-nephew of Revelation. He has impressive EPDs—the highest inner-muscular fat score of any bull in the sale.

“Turbo charge your program,” Donnell wrote on Page 67 of the sale catalog. “Thrust your program to the forefront of the fastest-growing breed in America with Turbo.” He expects $20,000 for the bull, plus an average of about $3,000 apiece for the 500 others.

And if all that isn’t enough good news, the Throckmorton Greyhounds are undefeated through seven games with Tucker Brown as quarterback.

Plus Jeff has a new girlfriend. Actually, two. The eight-day relationship did not work out, but now there is Hannah and there is Fatima. Hannah is pretty much perfect in every way but, Jeff says, she’s busy as a tick. The Fatima situation makes no sense whatsoever. She lives off in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, goes to happy hours and movies. She’d never even met a cowboy before Jeff. Makes no sense at all! How is it that they talk forever on the phone? Forever. He’s honest with her. He says: “There is Hannah.” He says: “I’m Christian and you’re Muslim. How would that deal work out? What would we do with our kids?” He says: “I’m not moving to no metroplex.” He says: “I’m a cowboy.”

Fatima drove all the way up from Dallas the night before—150 miles—to bring Jeff a present.

“What does a city girl know about a cowboy shirt?” Jeff is saying about the gift the next morning at the saddle house.

“You should have just told her thank you,” one of the other cowboys offers.

“But I didn’t understand it. I’m like huh? It had these shoulder flap deals. I’m like, what are these for?”

“You should have just said thank you.”

“She said she got it from some top-notch store,” Jeff says. “Norbert’s?”

“Nordstrom’s!”

Donnell walks up.

“Morning, gentlemen!” he says. “Ready to roll?”

“Yes, sir,” Jeff says. “We’ll get ’er loaded here in a moment.”

They’re headed to a ranch rodeo five hours away, for working cowboys only—not those highly paid professional bull riders you see on TV. This is ranch versus ranch, all the cowboys testing the skills they actually use each day. Roping, doctoring, milking, bronc riding. (No bull riding, because no working cowboy would ever have reason enough—or be stupid enough—to climb on the back of a bull.) Jeff will ride bronc tonight. On one hand it’s an honor to be the bronc rider but on the other hand it’s what you give to the young guy with no wife and no kids. Just in case.

They will take separate trucks, Donnell alone in his, because the others know better. Donnell can easily turn a five-hour trip into a ten-hour trip. Easily. He likes to stop and chat with customers. He’ll pass out sale catalogs and hang posters of Turbo at sale barns, feed stores, any place that looks good. He has a roll of tape in his truck.

Soon he is alone on Highway 183. A pickup approaches in the opposing lane and he raises two fingers, waves. He will do this over and over again, every truck he sees, until he reaches a town with too many to greet. Then, on the other side of that town he will wave again, truck by truck.

All the investors have said yes to the idea of cloning Revelation. Sometimes Donnell wishes one of them had said no. Sometimes it’s easier when God takes choices away from you. It’s up to Donnell now, up to him to call the lab.

His dad said no. Actually, his dad said, “Nah,” as in, Why in the world would you spend all that money on some dumb clone? It’s funny. Because his dad is the one who always wants to try awesome new things, and Donnell is the one clinging to good, conservative sense. You’d think their positions would be reversed.

But here’s his dad’s point: a better bull is on the horizon. Something even more amazing than Revelation will come along, so put your faith and your prayer and your energy there. In the future. Not the past.

It’s a tough one for Donnell to get. He’s a cowboy. A cowboy holds on to what is known and correct. It’s good to look forward, of course it is. But it’s hard to look forward when the past was so perfect.

He may yet decide to clone. He may not. But instead of idling, stuck in the mud of indecision, he thinks: Revelation plus AbiGrace. The top Red Angus bull. Donnell has the semen. The top Red Angus cow. He has the eggs.

And now he has the resulting embryos in 16 surrogate cows. This April, when the calves drop to the ground, he’ll see what he gets. He’ll see. Anyway, right now, he wishes he thought to bring a staple gun. Because tape won’t stick to a corkboard, and that’s the only place at this particular feed store where he’s allowed to put a poster. Other posters of other cattle are using up all the tacks, and he is not a man to take down another man’s poster.

He needs a staple gun, so he finds a Super Wal-Mart and pulls into the parking lot. He has on the spurs he won riding bronc at a ranch rodeo in 1989. He has on his fancy embroidered shirt. He notices a splotch of dried mud on his jeans. He takes out the knife he keeps clipped to his belt, unfolds it and scrapes. He reaches into the back of his truck, grabs his hat, the handsome black felt one he brings out each fall. He puts the hat on his head, positions it low, walks tall and listens to the gentle jingle of his spurs.

In this way, all dignity and elegance and fight, a cowboy enters Wal-Mart on an October afternoon full of steam, the way of sunshine after rain.

Jeanne Marie Laskas has written five nonfiction books and is working on one about overlooked American workers. Karen Kasmauski has photographed stories on six continents.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.