Buckhannon, West Virginia: The Perfect Birthplace

A community in the Allegheny foothills nurtured novelist Jayne Anne Phillips’ talent for storytelling

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Buckhannon-West-Virginia-parade-631.jpg)

I grew up in the dense, verdant Appalachia of the ‘50s and ‘60s. For me, “hometown” refers to a small town, home to generations of family, a place whose history is interspersed with family stories and myths. Buckhannon was a town of 6,500 or so then, nestled in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains of north-central West Virginia.

I left for college, but went “home” for years to see my divorced parents, and then to visit their graves in the rolling cemetery that splays its green acreage on either side of the winding road where my father taught me to drive. I know now that I loved Buckhannon, that its long history and layers of stories made it the perfect birthplace for a writer. My mother had grown up there, as had most of her friends, and their mothers before them. People stayed in Buckhannon all their lives. Despite the sometimes doubtful economy, no one wanted to leave, or so it seemed to me as a child.

Buckhannon was beautiful, the county seat, home to West Virginia Wesleyan, a Methodist college whose football field on College Avenue served both the college and high-school teams. Main Street was thriving. Local people owned the stores and restaurants. We lived out on a rural road in a ranch-style brick house my father had built. Two local newspapers, The Buckhannon Record and The Republican Delta, were delivered weekdays, thrust into the round receptacle next to our mailbox at the end of the driveway. My father went to town early on Sundays to buy the Charleston Gazette at the Acme Bookstore on Main Street. The Acme smelled of sawdust and sold newspapers, magazines, school supplies and comic books. Comic books were Sunday treats. I think of my father, vital and healthy, younger than I am now, perusing the racks, choosing a 15-cent Superman or Archie for my brothers, Millie the Model or a Classics Illustrated for me. An addicted reader early on, I first read R. D. Blackmore’s Lorna Doone and George Eliot’s Silas Marner as comics, before finding the original versions in the library, where I’d replenish armloads of borrowed books under my mother’s watchful eye. She’d finished college, studying at night while her children slept, and taught first grade in the same school her children attended.

I looked out the windows of Academy Primary School and saw, across South Kanawha Street, the large house in which my mother had lived until she married my father. My mother had graduated from high school in 1943, and my father, nearly a generation earlier, in 1928, but he wasn’t a true native. Born in neighboring Randolph County, he was raised by three doting paternal aunts. Each took him into their families for a few years, and he’d moved to Buckhannon for high school, winning the elocution contest and giving a speech at graduation. This fact always amazed me. My father, masculine in bearing and gesture, was not a talker. Women in Buckhannon told stories, and men were defined by their jobs. He attended the local college for a semester, then went to work, building roads, learning construction. His first name was Russell; for years, he owned a concrete company: Russ Concrete. My brothers and I rode to school past bus shelters emblazoned with the name. We seemed to have lived in Buckhannon forever.

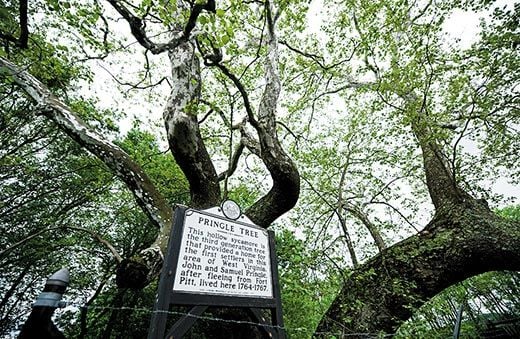

In a sense, we had. Both sides of the family had helped settle western Virginia when the land was still a territory. My mother traced her people back to a Revolutionary War Indian scout; a great-aunt had spoken of the “bad old days” of the Civil War. Her people had fought for the Union, but the Phillips men, a county south, were Confederates. The family donated the land for the Phillips Cemetery in the early 1870s, when the new state lay devastated in the wake of the war. Buckhannon families still told stories of those years. The past and the present were endlessly intermingled, and West Virginia history was an eighth-grade tradition. Every kid in town knew that English brothers John and Samuel Pringle had turned their backs on the English crown during the French and Indian War, deserting their posts at Fort Pitt in 1761 and traveling south on foot. They lived off the land for three years until they arrived at the mouth of what became the Buckhannon River, following it to find shelter in the vast cavity of a sycamore. The unmolested forests were full of gigantic trees 40 or 50 feet in circumference, and the 11-foot-deep cavity would have provided living space of about 100 square feet, the equivalent of a 10-by-10 room. The brothers survived the frigid winters on plentiful game, waiting out the war until they ran out of gunpowder. John Pringle traveled 200 miles for supplies and returned with news that amnesty was declared. The brothers moved to settlements farther south, but Samuel returned with a wife and other settlers whose names are common in Buckhannon today: Cutright, Jackson, Hughes.

Buckhannon adolescents still visit a third-generation descendant of the original sycamore on field trips. In 1964, my eighth-grade class drove to the meadow along Turkey Run Creek. The buses bounced and groaned, and we all lined up to walk into the tepee-size opening of what is still officially designated the Pringle Tree. I remember the loamy smell rising from the earth, damp, fertile and hidden. Somehow the version of the Pringle brothers’ story that we learned didn’t emphasize that they left a war to found a settlement in country so virgin and wild they had only to enter it to escape the bonds of military servitude. Wilderness was freedom.

The town was truly a rural paradise; even into the 1920s, some 2,000 farms, averaging 87 acres each, surrounded Buckhannon. Such small, nearly self-sufficient farms survived through the Depression and two world wars. Miners and farmers kept Main Street alive, and the town rituals, seasonal and dependable, provided a world. Everyone knew everyone, and everyone’s story was known. There were churches of every Protestant denomination and one Catholic parish. Parades were held on Veterans Day, Memorial Day and the Fourth of July. A week in the middle of May is still devoted to the Strawberry Festival. The populace lines up on the main thoroughfare to watch hours of marching bands, homemade floats and home-crowned royalty. The year my cousin was queen, I was 6 and one of the girls in her court. We wore white organdy dresses and waved regally from the queen’s frothy float. The parade wound its way through town, slowly, for hours, as though populating a collective dream. Though the queen wore her tiara all summer, the town’s everyday royalty were its doctors and dentists, the professors at the college, and the football coaches who’d taken the high-school team to the state championships three times in a decade. Doctors, especially respected and revered, made house calls.

The long dark hallway to our doctor’s office on Main Street led steeply upstairs and the black rubber treads on the steps absorbed all sound. Even the kids called him Jake. He was tall and bald and sardonic, and he could produce dimes from behind the necks and ears of his young patients, unfurling his closed hand to reveal the sparkle of the coin. The waiting room was always full and the office smelled strongly of rubbing alcohol. The walls were hung with framed collages of the hundreds of babies he’d delivered. My mother insisted on flu shots every year, and we kids dreaded them, but Jake was a master of distraction, bantering and performing while the nurse prepared slender hypodermics. After our shots, we picked cellophane-wrapped suckers from the candy jar, sauntered into the dim stairwell and floated straight down. The rectangular transom above the door to the street shone a dazzling white light. Out there, the three traffic lights on Main Street were changing with little clicks. We’d drive the two miles or so home, past the fairgrounds and fields, in my mother’s two-tone Mercury sedan. The car was aqua and white, big and flat as a boat. My father would be cooking fried potatoes in the kitchen, “starting supper,” the only domestic chore he ever performed. I knew he’d learned to peel potatoes in the Army, cutting their peels in one continuous spiral motion.

My dad, who was past 30 when he enlisted, served as an Army engineer and built airstrips in New Guinea throughout World War II, foreman to crews of G.I.’s and Papuan natives. He came back to Buckhannon after the war and met my mother at a Veterans of Foreign Wars dance in 1948. During the war she’d trained as a nurse in Washington, D.C. The big city was exciting, she told me, but the food was so bad all the girls took up smoking to cut their appetites. A family illness forced her return; she came home to nurse her mother. My grandmother was still well enough that my mother went out Saturday nights; she wore red lipstick and her dark hair in a chignon. My father looked at her across the dance floor of the VFW hall and told a friend, “I’m going to marry that girl.” He was 38; she, 23. He was handsome, a man about town; he had a job and a car, and his family owned a local hospital. They married three weeks later. In the winter of ‘53, when my mother had three young children under the age of 5, Dr. Jake made a house call. She was undernourished, he told her. Though she’d quit during her pregnancies, she was smoking again and down to 100 pounds. She told me how Jake sat beside her bed, his black medical bag on the floor. “Now,” he said, lighting two cigarettes, “we’re going to smoke this last one together.”

Hometowns are full of stories and memories rinsed with color. The dome of the courthouse in Buckhannon glowed gold, and Kanawha Hill was lined with tall trees whose dense, leafy branches met over the street. The branches lifted as cars passed, dappling sunlight or showering snow. Open fields bordered our house. Tasseled corn filled them in summer, and thick stalks of Queen Anne’s lace broke like fuzzy limbs. Cows grazing the high-banked meadow across the road gazed over at us placidly. They sometimes spooked and took off like clumsy girls, rolling their eyes and lolloping out of sight. Telephone numbers were three digits; ours was 788. The fields are gone now, but the number stays in my mind. Towns change; they grow or diminish, but hometowns remain as we left them. Later, they appear, brilliant with sounds and smells, intense, suspended images moving in time. We close our eyes and make them real.

Jayne Anne Phillips was a 2009 National Book Award finalist in fiction for her latest novel, Lark and Termite.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.