Catching the Bamboo Train

Rural Cambodians cobbled old tank parts and scrap lumber into an ingenious way to get around

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Norries-rickety-platform-631.jpg)

We were a few miles from the nearest village when we ran out of gas. The motor, a small thing perched on the back of a queen-size bamboo platform, spat out a few tubercular-sounding coughs and gave up. There were three of us riding this Frankenstein’s pump trolley, known in Cambodia as a norry, including my interpreter and the conductor, a short, elderly man with sunbaked skin and the permanent squint of failing eyesight. The morning was wretchedly hot, and in addition to a long-sleeved shirt and pants to block the sun, I wore a hat on my head and a scarf around my face. One could stay dry when moving along, the oncoming air acting like a mighty fan. But as the norry rolled to a slow stop, sweat bloomed on the skin almost instantly. I’d traveled across a broad stretch of Cambodia on the “bamboo train,” as this form of transportation is known in English, and now I considered what getting stuck here would mean.

The old man pointed down the line and mumbled in his native Khmer. “His house is nearby,” said Phichith Rithea, the 22-year-old interpreter. “He says it’s about 500 meters.” All I could see was heat-rippled air. Rithea pushed until he was ready to collapse, and the old man mumbled again. “He says we are nearly there,” Rithea translated as I took my turn pushing. The old man told me to walk on one of the rails to avoid snakes sunning on the metal ties. I slowed down as we approached a lone wooden train car converted to a house near where the old man had pointed. “That’s not it,” said Rithea. My head spun with heat and exhaustion. When we reached the old man’s house, we estimated that it was more than a mile from where we had broken down. The conductor filled our tank with a light-green liquid he kept in one-liter Coke bottles, and we were on our way, headed toward the capital, Phnom Penh.

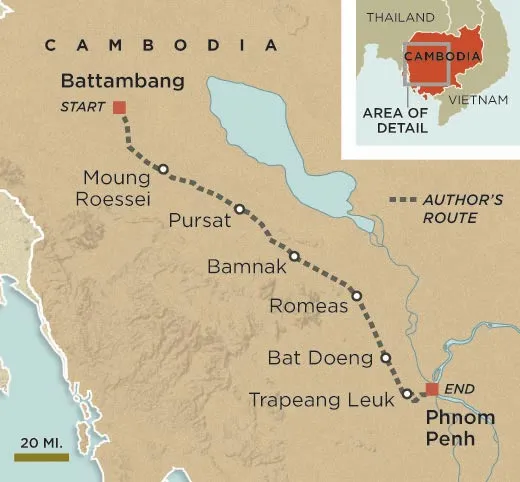

If you have the time, money and inclination, you can travel almost 11,000 miles from London to Singapore exclusively by train—except in Cambodia. It wasn’t always so. In the 1920s, the French started work on a railroad that would eventually run 400 miles across Cambodia in two major sections: the first from the Thai border, via Battambang, to Phnom Penh; the second from Phnom Penh to the coastal city of Sihanoukville to the south. The rail was a single line of meter-wide track, but it did the job, and people used it.

The years after French colonial rule, which ended in 1953, were characterized by instability and then civil war. In 1975, the Khmer Rouge regime evacuated Phnom Penh, reducing the city’s population from more than two million people to 10,000 in a single day. From then until the regime fell, in 1979, an estimated 1.4 million Cambodians, or about 20 percent of the total population, died from execution, starvation or overwork. A new psychology took root: say nothing unnecessary, think no original thoughts, do nothing to stand out. In other words, to demonstrate the very qualities that make us human was to consign oneself to a torture center like the notorious S-21 prison, and eventually a mass grave. The Khmer Rouge had a slogan:

To spare you is no profit, to destroy you is no loss.

From 1979 to the late 1990s, a guerrilla war burned through the country. Remnants of the Khmer Rouge mined the railroad extensively and frequently ambushed trains. An official from the Cambodian Ministry of Public Works and Transport told me that the ministry still wouldn’t guarantee that the rails had been fully cleared of land mines.

I went to Cambodia last June to ride the norries, which I’d heard about on previous travels to Southeast Asia, and to get a glimpse of rural life along the way. Passenger trains hadn’t run in over a year. And for quite some time before that, there had been only one train a week, taking about 16 hours to cover a route that took only five hours by bus; at speeds just faster than a jog, the train tended to break down or derail. At the train yard in Phnom Penh, I saw rows of derelict cars, some with interiors overgrown with plants, others whose floors had entirely rotted out. All that was left was the norry.

A norry is basically a breadbox-size motor on top of a bed-size bamboo platform on top of two independent sets of metal wheels—all held together by gravity. It’s built from bamboo, old tank parts and motors ripped from broken motorbikes, rice harvesters and tractors. To accelerate, the driver slides the motor backward, using a stick as a lever, to create enough tension in the rubber belt to rotate the rear axle. Though no two norries are identical, a failing part can be swapped with a replacement in a few seconds. Norries are technically illegal but nonetheless vital and, if you know where to look, ubiquitous.

I started just outside Battambang, on a 170-mile-long stretch of what was once the Northern Line. The “norry station” was little more than a few teak and bamboo homes at the dusty confluence of a dirt road and a set of old rails. When Rithea and I arrived, there were chickens, dogs and children scampering about and two cops lounging in the shade, chatting with the locals. Bamboo platforms, disembodied engines and old tank wheels welded in pairs to heavy axles were stacked near the tracks.

A man sitting on the rails had a prosthetic left leg, a few gold teeth and a disarming smile. He gave his name as Sean Seurm and his age as 66. He said he was a norry driver but complained that the local travelers used his services less often these days, having been replaced by foreign tourists looking for a 20-minute jaunt into the countryside. “We have less business, and now we have to pay the police,” said Seurm’s wife, Phek Teorng. Shaking down a norry driver ferrying locals at 50 cents a ride had probably not been worth the trouble, but tourists pay ten times that.

Over the next hour, at least five small groups of Western backpackers arrived to ride the norry. None of the locals was forthcoming when Rithea asked about our chances of catching one to Phnum Thippadei, about 18 miles away. A man with a tattoo of Angkor Wat on his chest intimated that we had no choice but to wait for the local vegetable norry, which wouldn’t leave until 4 a.m. When we came back to board it, the sky was dotted with glittering stars, the tiniest slice of crescent moon to the east, and the Milky Way’s surprisingly visible Great Rift.

The vegetable norry carried us a few miles down the track to meet up with one headed to Phnum Thippadei. It was less sturdy than I had imagined, with gaps in the bamboo wide enough to jam a finger through, and the platform vibrated at just the right frequency to make my legs itch. Our driver, standing near the back, used a headlamp as a signaling device for road crossings and upcoming stations, turning the rails to silver streaks darting into the undergrowth. I was mesmerized—until a shrub smacked me in the face. When another took a small chunk out of my right sleeve, I felt like a tyro for riding too close to the edge.

As I scrambled onto the norry to Phnum Thippadei, I inhaled an almost sickly sweet scent of overripe fruit; in addition to a few Cambodian women, we were carrying cargo that included a pile of spiky jackfruit the size of watermelons. “They sell vegetables along the way,” said Rithea as we rolled to a brief stop at a village. Most of the produce was dropped off, and before we pulled away, I saw nylon mats being unrolled and vegetables being set up by the rail—an impromptu market.

As the stars grew faint and the sky slowly faded to pink and yellow pastels ahead of a not-yet-risen sun, villagers lighted small gas lanterns at railside huts. At each stop, always where a dirt road intersected the rail, I heard voices droning in the distance. Rithea said they were monks chant-ing morning prayers or intoning the mournful words of a funeral or singing Buddhist poetry. It made me think of the Muslim call to prayer, or of Joseph Conrad’s Marlow awakening to a jungle incantation that “had a strange narcotic effect upon my half-awake senses.”

The sun was low in the sky when we pulled into Phnum Thippadei. A few dozen people squatted by the track or sat in plastic chairs eating a breakfast of ka tieu, a noodle soup. After some searching, we found a norry driver named Yan Baem and his sidekick, La Vanda, who dressed like a Miami bon vivant in a patterned white shirt with a wide collar, white pants and flip-flops. They said they’d take us to Moung Roessei, about 15 miles down the line, where Rithea thought we could get a norry to Pursat.

Now that the sun was up, I could see why the going was so rough: the tracks were woefully misaligned. Most of the rail was warped into a comical squiggle, as if it had been made of plastic and then deformed by a massive hair dryer. In some places, there were breaches in the rail more than four inches wide. With nothing to distract me, I focused meditatively on the click-CLANK-jolt, click-CLANK-jolt, click-CLANK-jolt of the ride, barely reacting when the norry hit a particularly bad gap in the track and the platform jumped the front axle and slid down the rail with all of us still seated. After a quick inspection, Baem and Vanda reassembled the norry and pressed on, a bit slower than before.

In Moung Roessei, we met Baem’s aunt, Keo Chendra, who was dressed in a floral magenta shirt and bright pink pajama pants. She insisted there were no norries going our way—but her husband, who owned a norry, would take us for a price. Rithea wanted to negotiate, but I had begun to suspect that “no norries running here” was just a way to get unsuspecting foreigners to overpay for a chartered ride and that Rithea was too polite to challenge such assertions. After all, we’d been told that no norries ran between Phnum Thippadei and Moung Roessei—and hadn’t we seen a handful traveling that route?

We decided to cool off in the shade for a bit. Chendra had a food stand, so we ordered plates of bai sach chrouk, a marinated, grilled pork dish over broken rice. After eating, we walked to what was once a sizable train station, the old buildings now crumbling shells, pockmarked and empty. A scribbled chalkboard that once announced the comings and goings of trains floated like a ghost near a boarded-up ticket window; passing nearby, a horse-drawn buggy kicked up dust.

A bit up the track, I saw four men loading a norry with the parts of a much bigger one built out of two-by-fours. The driver told us that the big norry was used to carry lumber from Pursat to Moung Roessei, Phnum Thippadei and Battambang, but that it was cheaper to transport the big norry back to Pursat on the smaller one. He said we could join them for the roughly 50-mile trip, no charge, though I insisted we pay, $10 for the two of us.

Less than a mile out, a norry stacked high with timber came clacking at us head-on. Fortunately, norry crews have developed an etiquette for dealing with such situations: the crew from the more heavily laden norry is obliged to help disassemble the lighter one, and, after passing it, reassemble it on the track.

The whole process usually takes about a minute, since two people can carry a typical bamboo norry. But the big two-by-four platform required six of us lifting with all our strength. Aside from narrowly missing a few cows foraging around the tracks, we made it to Pursat without incident. The norry station was a busy cluster of railside huts where one could buy food, drink and basic supplies. I had planned to leave the next morning, but a bout of food poisoning—was it the bai sach chrouk?—delayed us a day.

On our second morning, a thin, shirtless young man named Nem Neang asked if I wanted a ride to Bamnak, where he would be driving a passenger norry in about 15 minutes. Just what I needed. He said there were usually ten norries a day from Pursat, and for an average day of work he would collect 30,000 to 40,000 Cambodia riel (roughly $7 to $10). But he worried that the railroad was going to be improved—the Cambodian government is working on it— and that the laws against norries might actually be enforced.

Neang’s norry was crowded with 32 passengers, each of whom had paid the equivalent of 75 cents or less for the ride. At an early stop, a motorbike was brought on, and several passengers had to sit on it until more room opened up. Among this tightly packed crowd—a tangle of legs, bags and chatter—I met a Muslim woman named Khortayas, her hair covered in a floral head scarf, on her way to visit her sister in Bamnak. A merchant named Rath told me she took the norry twice each month to bring back beds to sell.

Near the town of Phumi O Spean, a small white dog started chasing the norry, trailing us relentlessly. As we slowed, the dog darted ahead, briefly running up the track as if it were our leader. The absurdity of the scene caused a minor sensation, and somebody suggested that the dog wanted a ride. Neang stopped, picked up the pup and brought it aboard. Our new canine friend rode the rest of the way, being stroked by one or another of the passengers or standing with two paws on the driver’s lap.

At Bamnak, we switched to a norry carrying concrete pipes, refined sugar, soy milk, crates of eggs and other supplies. In Kdol, we joined a young mother and her child on a norry returning from a lumber delivery. And in Romeas, we chartered a norry driven by a man who had bloodshot eyes and smelled of moonshine. The town of Bat Doeng had no guesthouse, but our norry driver’s brother, a construction worker named Seik Than, lived nearby and offered to let us stay with him. He and his wife, Chhorn Vany, grilled a whole chicken for our dinner.

It was in Bat Doeng that we boarded our final norry, the one driven by the man with the bum ankle and low fuel. Having to push part of the way made the journey to Trapeang Leuk seem a lot longer than 15-odd miles. From there—basically the end of the line—we caught a tuk-tuk, a type of auto-rickshaw, for the five-mile ride to Phnom Penh and a hot shower in a backpackers’ hotel. It felt like the height of luxury.

In the days that followed, whomever I told about the bamboo train seemed charmed by the novelty of the thing. But an English teacher from the United Kingdom whom I met at a café in Phnom Penh recognized something else.

“That’s great to hear,” he said.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because after what happened here, you worry about the state of the human spark. But this reassures me it’s still there.”

Russ Juskalian’s writing and photography have appeared in many publications. He is based in Brooklyn, New York.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.