Chile’s Driving Force

Once imprisoned by Pinochet, the new Socialist president Michelle Bachelet wants to spread the wealth initiated by the dictator’s economic policies

On the evening of March 12, a broadly smiling woman emerged on the balcony of La Moneda, Chile's presidential palace in the heart of Santiago, the capital. Inaugurated the day before as the first woman to be elected chief of state in that country, President Michelle Bachelet extended her arms, acknowledging the cheers of 200,000 compatriots in the broad square below. Chileans had gathered from communities all along this string bean of a country that stretches 2,600 miles from northern deserts through fertile central valleys to rain-drenched southern forests.

Bachelet, a 55-year-old Socialist, offered her audience a message of pain and redemption, drawn from her own personal experience. She recalled the numerous victims of the 17-year, right-wing dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet that ended in 1990. "How many of our loved ones cannot be with us tonight?" she asked, referring to the estimated 3,500 dead and "disappeared"—citizens taken from their homes, often in the dark of night, who were never heard from again. They included her own father, Alberto Bachelet, a left-wing air force general who was almost certainly tortured to death in prison after the 1973 coup that brought Pinochet to power. Bachelet, a 21-year-old student activist at the time, was also jailed and, she has said, blindfolded and beaten. "We are leaving that dramatically divided Chile behind," the president promised that March evening. "Today, Chile is already a new place."

So it would seem. Pinochet, now 90 years old and ailing in his suburban Santiago home at the foot of the snow-topped Andes, has become an object of scorn. His political measures are well documented: the several thousand Chileans killed and many thousands more jailed for having supported the freely elected government of President Salvador Allende, a Socialist who died during an assault on La Moneda Palace by Pinochet's forces 33 years ago in September.

Even most of the former dictator's admirers abandoned him after revelations since 2004 that he accumulated at least $27 million in secret bank accounts abroad, despite a modest military salary. Pinochet has evaded prison only because strokes and heart disease have left him too impaired to stand trial. "He has been so thoroughly discredited and humiliated that whether or not he ends up behind bars in a striped suit is almost immaterial," says José Zalaquett, 64, Chile's leading human rights lawyer.

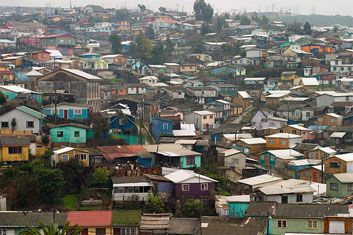

And yet, Pinochet's despotic but economically successful legacy remains troublingly ambiguous to many Chileans. Led by young, free-market policy makers, Pinochet privatized everything from mines to factories to social security. He welcomed foreign investment and lifted trade barriers, forcing Chilean businesses to compete with imports or close down. The reforms were wrenching. At one time, a third of the labor force was unemployed. But since the mid-1980s, the economy has averaged almost 6 percent annual growth, raising per capita income for the 16 million Chileans to more than $7,000—making them among the most prosperous people in South America—and creating a thriving middle class. Today, only 18.7 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, compared, for example, with 38.7 percent in Brazil and 62.4 percent in Bolivia. At this pace, Chile, within a generation, will become Latin America's most prosperous nation.

Neighboring countries, many of which embrace populist, left-wing economic policies, tend to resent Chile's growing prosperity, rooted as it is in the policies put in place by the region's most notorious dictator. "We can't go around rubbing our neo-capitalism in the faces of other Latin Americans," says Raul Sohr, a Chilean novelist and leading center-left political commentator. "Bachelet certainly won't do that."

At home, however, neo-capitalism has taken root. The democratically elected governments that have succeeded Pinochet in Chile have barely tinkered with the economic model he ushered in. "Voters figure that the same economic policies will continue no matter who gets elected," says former economics minister Sergio de Castro, 76, who forged many of the Pinochet-era reforms. "So, if the left wants to appropriate the model we created, well that's just fine."

But traveling across this irresistibly beautiful country, it is hard not to notice the tension between economic consensus and brutal recent history, the origins of which I observed firsthand as a Santiago-based foreign correspondent for the New York Times at the end of the Allende government and in the early Pinochet regime.

My most recent trip begins with a visit to a rodeo in Coronel, an agrarian community some 330 miles south of the capital. During the Allende years, militant peasant groups took over many farms and ranches, especially around Coronel. Conservative landowners here still display strong loyalties to Pinochet because he crushed the militants and returned their properties to them.

Thirty years ago, I reported on the peasant takeovers here. Today, I return to find the landscape transformed. Roads have been broadened and paved. Scruffy corn and wheat farms have given way to intensively cultivated fields of asparagus, berries, broccoli and fava beans. The highway to the Pacific Ocean port of Concepción, 14 miles north, is lined with factories where huge harvests of produce are frozen and packaged for export to the United States and other Northern Hemisphere markets.

The reasons for the agrarian boom are obvious to its beneficiaries, some of whom I meet at the Coronel rodeo. Pinochet's free-market regime offered farmers a crucial choice: fight a losing battle against cheaper grain imports from Argentina or develop products for export. A critical mass of farmers wisely—and ultimately successfully—chose the export route. "Pinochet saved us," says Marina Aravena, sitting in the rodeo stands next to her father, an elderly rancher and agribusiness owner. Bachelet's inauguration would take place during the rodeo weekend, but Aravena, like many of the 2,000 spectators, had no intention of watching the ceremony on television. "I'm not the least interested," she says.

At night, ranchers and spouses gather to celebrate the winning huasos—Chilean cowboys—inside the rodeo ground's makeshift banquet hall, a palm-thatched space with sawdust spread over the floor. Couples shuffle through the cueca, a popular dance that reminds me of a rooster trying to corner a hen. In a fast-changing, increasingly urbanized society, many Chileans seem eager to embrace huaso culture—with its emphasis on military bearing; mocking songs; and a hardy cuisine reliant on empanadas (meat-filled turnovers) and cazuela de carne (thick beef stew poured over rice).

The distinctive huaso culture grew out of geographical constraints. Because the country is so narrow—never wider than 120 miles from the Andes in the east to the Pacific in the west—ranches were always much smaller than in nearby Argentina, with its vast plains. Grazing lands in Chile weren't fenced off, so herds from neighboring ranches mingled and were separated only after they had fattened enough for slaughter. The most efficient way to cull animals was to lead them singly into corrals, each enclosure belonging to a different rancher. Therefore, a premium was placed on treating livestock gently; no one wanted to risk injuring a neighbor's cattle.

Tonight, at the long, wooden bar, boisterous huasos are sampling local cabernets and merlots. An argument ensues about a proposal to allow women to compete in future rodeos. "Anything can happen," says Rafael Bustillos, a 42-year-old huaso, with a shrug. "None of us could have imagined a woman president."

Bachelet would no doubt agree. "A few years ago, frankly, this would have been unthinkable," she told the Argentine congress on her first visit abroad, just ten days after assuming office. Discriminatory attitudes toward women, which had hardened during Pinochet's military dictatorship, lingered well after the restoration of democracy. (Divorce wasn't legalized until 2004; Chile was the last country in the Americas to do so.) Yet Bachelet is a single parent of three children.

She grew up the daughter of a career air force officer, moving around Chile as her father was posted from one base to another. In 1972, with the nation in economic chaos and nearing civil strife, President Allende appointed General Bachelet to enforce price controls on food products and ensure their distribution to poorer Chileans. "It would cost him his life," his daughter would recall in Michelle, a biography by Elizabeth Subercaseaux and Maly Sierra, recently published in Chile. General Bachelet's zeal for the task got him labeled an Allende sympathizer; he was arrested hours after the Pinochet-led coup that began on September 11, 1973, with the bombing of La Moneda. Michelle Bachelet watched the attack from the roof of her university and saw the presidential palace in flames. Six months later, her father died in prison, officially from a heart attack.

After her own brief imprisonment (no official charges were filed against her), Michelle Bachelet was deported to Australia, in 1975, but after a few months there she moved to East Berlin, where she enrolled in medical school. She married another Chilean exile, Jorge Dávalos, an architect who is the father of her two older children, Sebastián and Francisca. Bachelet speaks about her personal life with an openness unusual, especially among public figures, in this conservative Catholic country. She wed in a civil ceremony in East Germany, she told her biographers, only after she became pregnant. She separated from her husband, she added, because "the constant arguments and fights were not the sort of life I wanted for myself or my children." Returning to Chile four years later, in 1979, she earned degrees in surgery and pediatrics at the University of Chile's School of Medicine. At a Santiago hospital, she met a fellow doctor who, like Bachelet, was attending AIDS patients. The couple separated within months of the birth of their daughter, Sofia.

Following years of working as a doctor and administrator at public health agencies, Bachelet was named Minister of Health in 2000 by President Ricardo Lagos, a Socialist for whom she had campaigned. As a member of his cabinet, Bachelet quickly delivered on her public promise to end long waiting lines at government clinics. With her popularity soaring, Lagos tapped her in 2002 to be his Minister of Defense, the first woman to occupy that post and a controversial appointment, considering her father's fate. "I'm not an angel," she told the New York Times that year. "I haven't forgotten. It left pain. But I have tried to channel that pain into a constructive realm. I insist on the idea that what we lived through here in Chile was so painful, so terrible, that I wouldn't wish for anyone to live through our situation again." By most accounts, the daughter proved popular among army officers for working hard to dissolve lingering distrust between the armed forces and center-left politicians. In 2003, on her watch, army commander in chief Gen. Juan Emilio Cheyre publicly vowed that the military would "never again" carry out a coup or interfere in politics.

Bachelet won the presidency in a runoff on January 15, 2006, with 53.5 percent of the vote against conservative Sebastián Piñera, a billionaire businessman. She named women to half of 20 posts in her cabinet, including Karen Poniachik, 40, as minister of mining and energy. "When I visit my supermarket, women clerks and customers—even some who admit not having voted for Bachelet—tell me how good they feel about seeing women at the top levels of government," says Poniachik, a former journalist. But many others, particularly in the business world, where a bias against women is widespread, sound uneasy.

Mine owners, in particular, have distrusted Socialists since the Allende years. Calling copper "the wages of Chile," Allende nationalized the biggest mines, which happened to be owned by U.S. companies. That action provoked the ire of Washington, and soon the Central Intelligence Agency was abetting plotters against Allende. The Marxist president had failed to gain the support of most copper miners, who considered themselves the country's blue-collar elite. Angered by hyperinflation that undercut their paychecks, many joined general strikes—in part financed by the CIA—that weakened Allende and set the stage for his overthrow. Under Pinochet, most state mines were sold back to private investors, both foreign and Chilean. Low taxes and minimal interference let mine owners raise technology levels, improve labor conditions and vastly increase production. And the center-left civilian governments that followed Pinochet have pursued the same policies. Several South American countries, including Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador, are increasing state control of natural resources. "But in Chile, it's not even an issue," says Poniachik. "Everybody thinks private investment has been positive in all aspects of mining."

Most of Chile's copper mines are in the dry and cloudless desert north. One of the biggest, Los Pelambres, some 125 miles north of Santiago, is largely owned by the family of Andrónico Luksic, who died last year at 78. As a young man, Luksic sold his stake in a small ore deposit he had discovered to investors from Japan. The Japanese thought the price Luksic had quoted them was in dollars when in fact it was in Chilean pesos. As a result, Luksic was paid a half-million dollars, or more than ten times his asking price. This marked the beginning of his stupendous fortune. Last year, Los Pelambres earned $1.5 billion, thanks to record copper prices stoked by booming Asian economies. "Prices will stay high for at least the next three years," says Luis Novoa, a financial executive at Los Pelambres. "China and India just keep growing and need all the copper we can sell them."

At the upper edge of Los Pelambres, 11,500 feet high, the air is so thin and clear that the ridges from exhausted copper veins appear closer than they are, as do mammoth mechanized shovels scooping up new ore deposits at the bottom of the canyon-size pit. "All these deposits were once liquid magma—molten rock deep below the surface—and could have spewed out of volcanoes, like what happened all over Chile," says Alvio Zuccone, the mine's chief geologist. "But instead the magma cooled and hardened into mineral deposits."

The deposits contain less than 1 percent copper; after excavation, they must be crushed, concentrated and dissolved into a water emulsion that is piped to a Pacific port about 65 miles west. There the emulsion is dried into a cake (now 40 percent copper) and shipped, mostly to Asia. The Los Pelambres work is the simplest part of the process. "We're just a bunch of rock grinders," says Zuccone.

Because mining takes place in the almost unpopulated northern deserts, it has escaped environmental controversy. But forestry has stirred heated debate. "Under the volcanoes, beside the snow-capped mountains, among the huge lakes, the fragrant, the silent, the tangled Chilean forest," wrote Pablo Neruda (1904-73), Chile's Nobel laureate poet, about his childhood in the country's wooded south. Today, little of his beloved forest survives. Gone are the bird that "sings like an oboe," and the scents of wild herbs that "flood my whole being," as Neruda recalled. Like yellow capillaries, timber access roads and bald patches scar the green hillsides.

In 1992, American entrepreneur Douglas Tompkins used some of the proceeds from the sale of his majority stake in the sportswear firm Esprit to create a refuge for Chile's shrinking, ancient forests at Pumalín, a private park encompassing 738,000 acres of virgin woodlands some 800 miles south of Santiago. Initially, Pumalín was hugely controversial. Ultranationalists claimed that because it amounted to a foreign-owned preserve that bisected the country, it threatened Chile's security. But opposition dissolved once it became clear that Tompkins' intentions were benign. Several Chilean billionaires have followed his example and bought vast forest expanses to preserve as parks. (In Argentina, however, where Tompkins created a 741,000-acre preserve, opposition to foreign ownership of environmental refuges has intensified. Critics there are calling for Tompkins to divest—despite his stated intention to donate holdings to the government.)

Pumalín is also important because it is one of the few temperate rain forests in the world. Annual rainfall here totals a startling 20 feet. As in tropical jungles, the majority of trees never lose their foliage. Moss and lichen blanket trunks. Ferns grow nine feet tall. Stands of woolly bamboo rise much higher. And other plant species scale tree branches, seeking out the sun. "You see the same interdependence of species and fragility of soils that exist in the Amazon," says a guide, Mauricio Igor, 39, a descendant of the Mapuche Indians who thrived in these forests before the European conquest.

Alerce trees grow as tall as sequoias and live as long. Their seeds take a half century to germinate, and the trees grow only an inch or two a year. But their wood, which is extremely hard, has long been prized in house construction, and despite decades of official prohibitions against its use, poachers have brought the species to the verge of extinction. Pumalín is part of the last redoubt of the alerce—750,000 acres of contiguous forest stretching down from the Andes on the Argentine border to the Chilean fiords on the Pacific.

In a cathedral stand of alerces, Igor points out one with a 20-foot circumference, rising almost 200 feet and believed to be more than 3,000 years old. Its roots are entwined with those of a half-dozen other species. Its trunk is draped in red flowers. "I doubt even this tree would have survived if Pumalín didn't exist," he says.

Mexico City and Lima built imposing Baroque-style palaces and churches with the silver bonanzas mined in Mexico and Peru during the 1600s and 1700s. But the oldest structures in Santiago date back only to the 19th century. "Chile was on the margins of the Spanish Empire, and its austere architecture reflected its modest economic circumstances," says Antonio Sahady, director of the Institute of Architectural Restoration at the University of Chile, which has helped preserve older Santiago neighborhoods.

Now Santiago's more affluent citizens are moving eastward into newer districts closer to the Andes. "They have embraced the California model of the suburban house with a garden and a close view of the mountains—and of course, the shopping mall," says Sahady. I drop by a mirrored high-rise where one of the city's largest real estate developers has its headquarters. Sergio de Castro, Pinochet's former economics minister and architect of his reforms, is chairman of the company.

De Castro was the leader of "the Chicago boys," a score of Chileans who studied economics at the University of Chicago in the 1950s and '60s and became enamored with the free-market ideology of Milton Friedman, a Nobel laureate then teaching at the school. Once installed in the highest reaches of the Pinochet regime, the Chicago boys put into practice neo-capitalist notions beyond anything Friedman was advocating.

"Maybe the most radical of these ideas was to privatize the social security system," says de Castro. To be sure, by the time the Allende government was overthrown in 1973, payments to retirees had become virtually worthless because of hyperinflation. But nowhere in the world had private pension funds replaced a state-run social security system. Under the system put in place in 1981, employees hand over 12.5 percent of their monthly salaries to the fund management company of their choice. The company invests the money into stocks and bonds. In theory, these investments guarantee "a dignified retirement"—as the system's slogan asserts—after a quarter-century of contributions. President Bush, who visited Chile in November 2004, praised the country's privatized pension system and suggested it could offer guidance for the Social Security overhaul that he was then advocating at home.

The positive effects on the Chilean economy became apparent much sooner. As pension fund contributions mushroomed into billions of dollars, Chile created the only domestic capital market in Latin America. Rather than having to depend on high-interest loans from global banks, Chilean firms could raise money by selling their stocks and bonds to private pension fund management companies. "This was a crucial element in our economic growth," says de Castro. Government emissaries from elsewhere in Latin America and as far away as Eastern Europe flocked to Santiago to learn about the system—and install versions in their own countries.

But seven years ago Yazmir Fariña, an accountant at the University of Chile, began to notice something amiss. Retired university professors, administrators and blue-collar employees were complaining that they were receiving much less than they expected, while the small minority who stayed with the old, maligned, state-run social security system were doing quite well. "We began doing research across the country, just among public employees," says Fariña, 53. "More than 12,000 retirees immediately sent us complaints that they were making a fraction of what they had been promised. We discovered a nationwide catastrophe." According to spokespersons for the private pension funds, only those retirees who failed to make regular contributions are suffering a shortfall in their retirement checks. But this is disputed by many retirees.

Graciela Ortíz, 65, a retired government lawyer, gets a pension of $600 a month—less than a third of what she expected. Her friend, María Bustos, 63, the former chief public accountant for Chile's internal revenue service, lives on $500 a month. And Abraham Balda, 66, a night guard at the university for 35 years, subsists on a monthly pension of $170. "The private pension funds are helping the country grow," says Fariña, who formed an association of retirees to lobby for lost benefits and pension reform. "But whatever happened to a ‘dignified retirement'?"

Fariña's association has ballooned to 120,000 members. More important, their complaints became the biggest issue of the recent presidential campaign. The retirees probably gave Bachelet a decisive edge in her victory.

On that March 12 evening following her inauguration, the new president made a long list of promises to the many thousands of spectators gathered below the balcony of the presidential palace. Their loudest cheers erupted when she promised to fix the private pension system. "What could be better than finishing off in 2010 with a great social protection system for all citizens?" she asked. And what could be better than a major economic reform that a freely elected Chilean government could call its own?

Jonathan Kandell, a New York Times correspondent in Chile during the 1970s, writes about economics and culture.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.