Cleveland’s Signs of Renewal

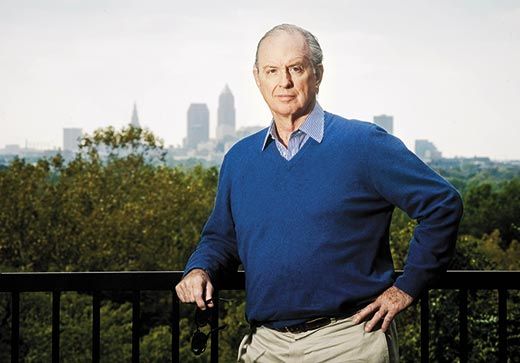

Returning to his native Ohio, author Charles Michener marvels at the city’s ability to reinvent itself

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/My-Kind-of-Town-Cleveland-Ohio-East-4th-Street-631.jpg)

On Saturday mornings when I was 11 or 12, my mother would drop me off at the Rapid Transit stop nearest our home in Pepper Pike, an outlying suburb of Cleveland. There, I would board a train for the 30-minute trip to an orthodontist’s office downtown. Despite the prospect of having my braces fiddled with, it was a trip I could hardly wait to take. From my seat on the train, nose pressed to the window, I was spellbound by the city to which I have lately returned.

First came the procession of grand houses that lined the tracks along Shaker Boulevard in Shaker Heights—in the 1950s, one of the most affluent suburbs in America. Set behind giant elms, their picturesque fairy tale facades transported me into my favorite adventure stories—The Boy’s King Arthur, The Count of Monte Cristo, The Hound of the Baskervilles. After the stop at Shaker Square, an elegant Williamsburg-styled shopping center built in the late 1920s, we entered a world of small frame houses with rickety porches and postage-stamp backyards. These belonged to the workers who produced the light bulbs, steel supports, paint and myriad machine parts that had made Cleveland a colossus of American manufacturing.

The train slowed as it passed the smoke-belching Republic Steel plant. Then we plunged underground and crept to our final destination in Cleveland’s Terminal Tower, which we boasted was “America’s tallest skyscraper outside New York.”

From the orthodontist’s chair high in the tower, I could see the city’s tentacles: spacious avenues of neo-Classical- style government and office buildings; graceful bridges spanning the winding Cuyahoga River, which separated the hilly East Side (where I lived) from the flatter, more blue-collar West Side. Stretching along the northern horizon was Lake Erie—an expanse so big you couldn’t see Canada on the other side.

Once free from the orthodontist’s clutches, the city was mine to explore: the gleaming escalators in the bustling, multifloored department stores; the movie palaces with their tinted posters of Stewart Granger and Ava Gardner; the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument with its bronze tableau of Lincoln and his Civil War generals; the sheet-music department at S.S. Kresge’s where I could hand the latest hits by Patti Page or the Crew-Cuts to the orange-haired lady at the piano and listen to her thump them out. There might be an Indians game to sneak into, or even a matinee performance by the Metropolitan Opera if the company was making its annual weeklong visit to the Public Auditorium.

This was the magical place that Forbes magazine, in one of those “best and worst” lists that clutter the Internet, named last year “the most miserable city in America.” Several statistics seemed to support this damning conclusion. During the 50 years since I left for college back East and a career in New York, Cleveland’s population has declined to something around 430,000—less than half of what it was when, in 1950, it ranked as the seventh-largest city in America. The number of impoverished residents is high; the big downtown department stores are shuttered; many of the old factories are boarded up.

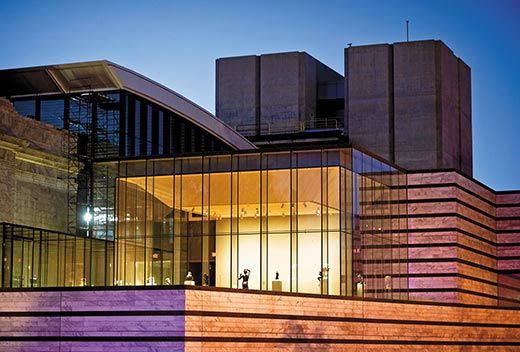

And yet four years ago, I couldn’t resist a call to return. The spark had been an article I wrote about the world-famous Cleveland Orchestra, still flourishing in its opulent home, Severance Hall, where I acquired my love of classical music. Across the street, waterfowl still flocked to the lagoon at the Cleveland Museum of Art, which had begun a $350 million renovation to house its superb holdings of Egyptian mummies, classical sculpture, Asian treasures, Rembrandts and Warhols.

The region’s “Emerald Necklace”—an elaborate network of nature trails—was intact, as was the canopy of magnificent trees that had given Cleveland its Forest City nickname. Despite the lack of a championship in more than 45 years, the football Browns and baseball Indians were still filling handsome new stadiums—as was the local basketball hero LeBron James, who was making the Cleveland Cavaliers an NBA contender.

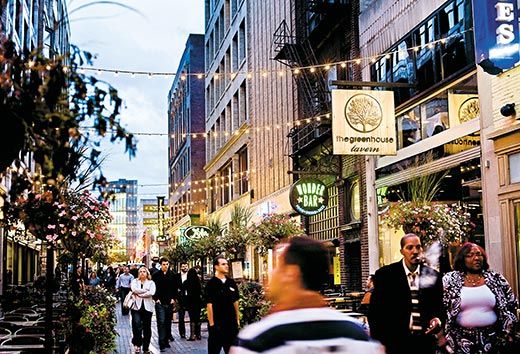

Signs of renewed vitality were everywhere. Downtown warehouses had been turned into lofts and restaurants. Several old movie palaces had been transformed into Playhouse Square, the country’s largest performing arts complex after Lincoln Center. The lakefront boasted the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, in a futuristic design by I. M. Pei. The Cleveland Clinic had become a world center of medical innovation and was spawning a growing industry of biotechnology start-ups. How had so depleted a city managed to preserve and enlarge upon so many assets? And could a city that had once been a national leader in industrial patents in the 19th century reinvent itself as an economic powerhouse in the 21st?

“It’s the people,” a woman who had recently arrived in Cleveland said when I asked what she liked most about the place. As with so many transplants to the area, she was here not by choice but by virtue of a spouse’s change of job. They had traded a house in Santa Barbara and year-round sun and warmth for an old estate on the East Side and gray winters and sometimes torrid summers. And yet they didn’t look back. “We’ve been amazed by how welcoming everyone is,” she added. “We’ve never lived in a place where everyone is so involved in its future.”

For me, returning to Cleveland has given new meaning to the idea of community. Clevelanders, as even people in the outer suburbs call themselves, are early risers—I’d never before had to schedule so many breakfast appointments at 7:30 a.m. And they find plenty of time to attend countless meetings about how to reform local government, foster better cooperation among the checkerboard of municipalities or develop a more “sustainable” region. The appetite of Clevelanders for civic engagement was implanted nearly a century ago when city fathers created a couple of models that have been widely imitated elsewhere: the Cleveland Foundation, a community-funded philanthropy, and the City Club of Cleveland, which proclaims itself the oldest, continuous forum of free speech in America.

Clevelanders aren’t exactly Eastern or Midwestern, but an amalgam that combines the skeptical reserve of the former with the open pragmatism of the latter. (My mother would say the Midwest really began on the flat west side of the Cuyahoga.) There is still a strain of class resentment, a legacy of Cleveland’s long history as a factory town. But since my return, I’ve never been embroiled in a strident political discussion or a show of unfriendliness. Clevelanders may not tell you to your face what they think of you, but they’re willing to give you the benefit of the doubt.

If there’s one trait that Clevelanders seem to possess in abundance, it’s the ability to reinvent oneself. I’m thinking of a new friend, Mansfield Frazier, an African-American online columnist and entrepreneur. When we first met for lunch, he blandly told me that he had served five federal prison sentences for making counterfeit credit cards. With that behind him, he’s developing a winery in the Hough neighborhood—the scene of a devastating race riot in 1966. A champion talker, he takes his personal motto from Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world.”

Then there’s the bookseller I met one afternoon in a run-down section of the West Side that has recently transformed itself into the hopping Gordon Square Arts District. The shop (which has since closed) had an intriguing name—84 Charing Cross Bookstore. Inside, I discovered a wall of volumes devoted to Cleveland history: books about the Connecticut surveyor Moses Cleaveland who founded the city in 1796; the 19th-century colony of Shakers who imbued the region with its value of industriousness; and “Millionaire’s Row,” a stretch of 40 mansions along Euclid Avenue that once housed some of America’s richest industrialists, including John D. Rockefeller.

As I handed the elderly man behind the counter a credit card, I asked how long he’d had the bookstore. “About 30 years,” he said. Was this line of work always his ambition? “No,” he said. “I used to be in law enforcement.” “How so?” I asked. “I was the city’s chief of police,” he said matter-of-factly.

Unlike the gaudy attractions of New York or Chicago, which advertise themselves at every opportunity, Cleveland’s treasures require a taste for discovery. You might be astonished, as I was one Tuesday evening, to wander into Nighttown, a venerable jazz saloon in Cleveland Heights, and encounter the entire Count Basie Orchestra, blasting away on the bandstand. Or find yourself in Aldo’s, a tiny Italian restaurant in the working-class neighborhood of Brook-lyn. It’s a dead ringer for Rao’s, New York’s most celebrated hole-in-the-wall, only here you don’t have to know someone to get a table, and the homemade lasagna is better.

The nearly three million residents of Greater Cleveland are as diverse as America. They range from Amish farmers who still refuse the corrupting influence of automobiles to newly arrived Asians who view the city’s inexpensive housing stock and biotechnology start-ups as harbingers of a brighter tomorrow. Despite their outward differences, I’m sure that every Clevelander was as outraged as I was by Forbes’ superficial judgment about what it’s like to actually live here. And they rose as one in unforgiving disgust when LeBron James deserted them for Miami last summer.

Cities aren’t statistics—they’re complex, human mechanisms of not-so-buried pasts and not-so-certain futures. Returning to Cleveland after so many years away, I feel lucky to be back in the town I can once again call home.

Charles Michener is writing a book about Cleveland entitled The Hidden City.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.