Climbing the Via Ferrata

In Italy’s Dolomites, a Hike Through World War I History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/viaferrata_631.jpg)

From my lofty perch 8,900 feet above sea level in Italy’s Dolomite Mountains, the view is spectacular. Towering peaks frame an idyllic Alpine valley, with deep-green pine forests and golden foothills.

It’s hard to believe that just 90 or so years ago, during World War I, these mountains were wracked by violence: explosions blew off summits and shrapnel pierced tree trunks. Even now, the ground is littered with bits of barbed wire and other debris from the conflict.

Thanks to a network of fixed climbing routes installed during the war, this breathtaking vista and history-rich area is accessible to anyone, not just experienced climbers. The routes, rigged with cables and ropes, were developed by troops as supply lines, to haul gear up the mountains. After the war, mountaineers appropriated them, creating what’s known as the Via Ferrata, or “Iron Way.”

My climbing partner, Joe Wilcox, and I chose September, the end of the climbing season, to explore the routes. We based ourselves in Cortina d’Ampezzo, a ski village with cobbled streets, small inns and chic shops—and the setting for the 1956 Winter Olympics and the 1963 movie The Pink Panther.

The gear list for climbing the Via Ferrata is short: a waist harness, helmet and Y-shaped rig of short ropes. The tops of the rig end in carabiners—metal rings with spring-hinged sides that open and close—which clip onto a permanent metal cable bolted to the mountain. The cable is the climber’s lifeline. The carabiner-free end ties to the harness.

Electrical storms kept us from climbing the first day, so we took a cable car up a nearby peak, 9,061-foot Lagazuoi. When Italy declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire in May 1915, this border area of South Tyrol was under Austro-Hungarian rule. To more easily defend the region, Austrian troops moved from valley towns like Cortina to a line of fortifications on Lagazuoi and other peaks, forming the “Dolomite front.” Both sides built supply lines up the mountains.

On the night of October 18, 1915, Italian soldiers scaled Lagazoui’s east flank to a ledge midway up the mountain. Under the ledge, the soldiers were protected from Austrian guns above and able to fire on Austrian trenches below. The Austrians tried dangling soldiers from the top of the mountain armed with grenades to toss on the Italians encamped on the ledge, with little success. With both sides stymied by not being able to directly reach the other, the war went underground.

From the summit of Lagazuoi, Joe and I walked east to a tunnel complex inside the mountain dug by Italian soldiers during the war. Both the Austrians and the Italians tunneled, to create bunkers, lookout positions and mine shafts under enemy bunkers, which would be filled with dynamite and detonated. Five major explosions rocked Lagazuoi from 1915 to 1917, turning its south face into an angled jumble of scree, wood scraps, rusted barbed wire and the occasional human bone.

Next we headed west across the rubble-strewn peak to the Austrian tunnel complex (enemy positions on Lagazuoi were as close as 90 feet). The Austrians built narrower and shorter tunnels than the Italians, both here and elsewhere in the South Tyrol. The Italians typically chiseled upward, letting gravity dispose of the rubble, then loaded the tops of the tunnels with dynamite to blow up the Austrian bunkers above. The Austrians dug downward, lifting out the chopped rock, to explode dynamite in a mine shaft that would intercept an Italian tunnel heading upward. On Lagazuoi, outside an Austrian tunnel, we uncovered rusted coils of iron cable, the kind still found on the Via Ferrata.

The next day, the weather clear, we headed out to climb the Via Ferrata at last. The route was three miles east of Lagazuoi on 8,900-foot Punta Anna. We clipped our ropes onto a cable and began the ascent, a mixture of hiking and climbing. The cable is bolted into the rock face about every ten feet, so at each bolt, we paused to remove our carabiners and move them to the next section of cable.

The first rule of climbing the Via Ferrata is preserving a constant connection with the cable. This means moving the carabiners one at a time. Up we went, slowly, around the ragged cone of Punta Anna, until we reached a vista overlooking a valley. On our left, the village of Cortina, at the foot of a snowy massif, looked like a jumble of dollhouses. Straight ahead were a cluster of craggy spires called Cinque Torri. On the right was the peak Col di Lana, site of one of the area’s most famous World War I battles.

Like Lagazuoi, 8,100-foot Col di Lana was held by Austria at the start of the war. In early 1916, the Italians decided to dynamite Austria off the mountain. They spent three months carving a tunnel that climbed at a 15-degree angle inside the mountain. By mid-March, Austrian troops in their bunkers atop the mountain could hear chiseling and hammering beneath them. Instead of abandoning their post, Austrian troops were commanded to stay. Military strategists feared that retreating could open up a hole in the frontline, leading to a larger breach. But, says local historian and author Michael Wachtler, there was also a mind-set on both sides that troops should stay on summits regardless of casualties.

“The big decisions were taken far away in Vienna, and there the deaths of more or fewer soldiers was not so important,” says Wachtler. “The opinion of the supreme command was to hold positions until the last survivor.”

On April 14, 1916, the noise finally stopped. Italy’s tunnel was by then about 160 feet long and ended 12 feet below the Austrian bunker. There was nothing to do but wait—it became a matter of which Austrian troops would be on duty when the summit exploded.

It took Italian troops three day to load five and a half tons of nitroglycerin into the underground shaft. When it was finally detonated at 11:35 p.m. on April 17, one hundred men died. The mountain’s summit was now a crater and about 90 feet lower than before. Inside the Austrian bunker, 60 troops remained, prepared to fight. But after realizing fumes would kill them if they stayed, they surrendered.

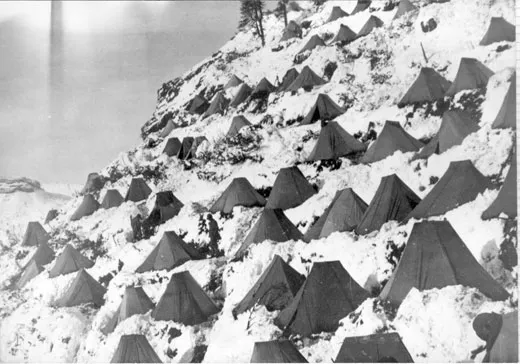

By the time the Dolamite front was abandoned in late 1917, some 18,000 men had died on the Col di Lana, according to Wachtler. About two-thirds of these deaths were caused not by explosives but by avalanches. A record snowfall in 1916 dumped as much as 12 feet of snow. Tunneling inside the mountains by both the Austrians and Italians served to increase the risk of avalanches. As two enemies fought to capture a mountain, it was ultimately the force of the mountain itself that inflicted the battles’ greatest casualties.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.