Cold, Hungry and Happy in the High Andes

40 bucks in cash, a warm sleeping bag and plenty of wine carry the author through his final days in Ecuador, in the remote high country outside of Quito

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130308114119CotopaxiRoad2.jpg)

I had only $40 in my wallet, but cash doesn’t help a person much on the freezing Andean tundra. Instead, my most valuable assets at the moment were two beers, some quinoa and two avocados for dinner—plus a riveting book about the hunt for a man-eating Siberian tiger by John Vaillant. Tent-bound life was good here in the high country. My hands were numb, but I was camped under the roof of a sheltered barbecue hut, and I dared the volcano to give me all the weather it could muster. The mountain seemed to answer. Wind and clouds swirled off the white, freshly dusted slopes, and rain began to fall as darkness crept on, but I stayed dry and cozy. It seemed very strange that millions of people dwelt just a few miles away in Quito, Ecuador, yet I was the only person on earth camped that night in Cotopaxi National Park.

The next morning was foggy and bit with such cold that I couldn’t get moving until past 9. When blue patches of sky gleamed with the promise of a warm day, I started cycling, and by the time I had reached the foot of the mountain, the sun was out in force, though the wind ripping across this barren plateau remained bitterly cold.

A group of Germans stepped off a tour bus at a roadside trailhead, aiming to spend the morning hiking around Laguna Limpiopungu, a shallow lake on the high plains just under the summit. When they learned I had biked to this remote spot, they gave me a round of applause. I was a bit confused and embarrassed, and I deflected the gesture with a wave of my hands.

“I met a Mexican man in Quito who had spent a year on his bike,” I told them. “And I met a British couple in Cuenca who were halfway into an 18-month trip. And I met a Colombian man in the Amazon who was walking to Argentina. I have been here two months, and my trip is about over. This is nothing.”

Cotopaxi National Park is barren and wildly beautiful but not very extensive. Sadly, I was out of the park by 1 p.m.—but more volcanic giants and frigid high country remained ahead. There were the massive peaks of Antisana, Cayambe and Pichincha, lands where camping was free and money good for only the barest joys of life—coffee, food and wine. I rolled north via a dirt road, which shortly turned to cobblestone, and as I came slowly over a rise, I abruptly saw my final destination in the distance: Quito, that beautiful but monstrous city encased in a basin by classic cone-shaped volcanoes. After weeks of traveling through rural, mountainous country of similar stature and poise, I had to wonder how and why the village that once was Quito had ballooned into such a behemoth.

With permission from the owner—plus a payment of five bucks—I camped that night in a soccer field in the Quito suburb of Sangolqui. I had $35 left—then $20 after buying food and wine the next morning. I set my sights on Antisana National Reserve and I started again uphill, against the rush-hour traffic flowing toward the capital. The scent of the city faded, and quietude returned as I ascended into the high, windswept valleys and plains that sprawled beneath the landscape’s centerpiece, the three-mile-high Volcán Antisana. At the park entrance, an employee assured me, after I asked, that I could camp at the end of the road. When I arrived, however, a group of bundled up men at the Ministry of the Environment refuge said the opposite—that there was no camping here.

“Why did that man tell me there was?” I asked, frustrated beyond my ability to explain in Spanish. I was 20 kilometers from the nearest designated campsite (Hosteria Guaytara, outside the park) with the sun slipping behind the peaks and my hands already numb within my alpaca gloves. The men recognized my dilemma. “It is not permitted but we can let you stay,” one said. He offered me a cabin of my own—but I chose to camp under a thatched roofed shelter in back. I was half frozen by the time I slipped into my sleeping bag and put my quinoa on the stove. I uncorked a bottle of Malbec from Argentina, and sweet, sweet coziness set in. I was camped for the first time in my life above 13,000 feet—13,041, exactly—and it was the coldest night of the trip.

At just past dawn, I was pedaling along the gravel road again. Like some wretched tramp in a Charles Dickens story, I jumped off my bike and pounced on a 10-dollar bill in the road, jammed against a rock and ready to sail away with the next gust. What a miracle! I was back to $30. I descended to the main highway, turned right and started uphill toward Cayambe-Coca Ecological Reserve, which would be my last dance with the high country. At sundown, still below the 13,000-foot pass and fearful that I might be sleeping in the rain behind a roadside gravel heap, I stopped in at a restaurant at kilometer 20, in Peñas Blancas, and asked if I could camp. The landlady took me to the balcony and spread her arms across the property below. “Wherever you like,” she said. “Can I pay you?” I asked. She waved the back of her hand at my offer. I went down and scouted for a spot amid the mud, gravel, dog poop and broken machinery, and, when it was dark, slipped into a relatively clean shed. A large animal was busy at some task in the attic, rattling the corrugated metal roof and a pile of lumber, and I zipped myself into my tent. For breakfast, I bought coffee and carrot juice, thanked the woman again and headed onward up the grade—with $23 in cash and no ATM for miles.

At the blustery pass was a sign reminding travelers to beware of a local imperiled species—the spectacled bear. The animals are rare throughout their Andean range, from Venezuela to Argentina, and their numbers may be dropping. Yet they are the pride of many locals, who wear hats or shirts bearing the animal’s image—distinctive with its panda-like face.

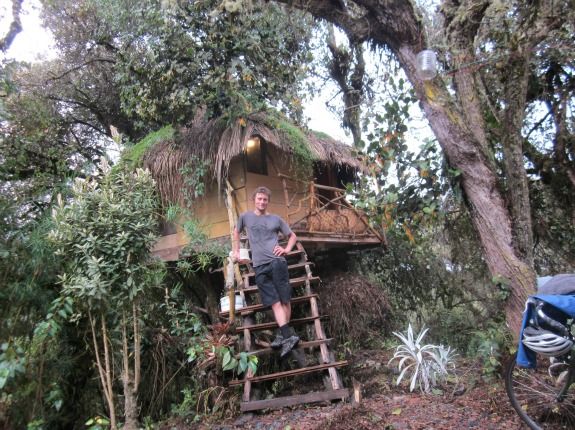

In Pampallacta, a thermal hot springs resort town, I spent $2 on fruit, $2 on cheese, $1 on a small bag of oats and—I couldn’t resist—$8 on a liter of wine. That gave me $10 left. I would have to camp somewhere, and I returned up the highway, toward Quito, to a resort on the north side of the road. Here, in the woods, I found a Swiss Family Robinson-style compound with $5 campsites. The owner said that for $6 I could stay in a cabin. He pointed to a wooden shack in the nearby canopy—the sort of treehouse that little boys dream of. I took it. I handed him a ten, and he handed back $4. This would have to carry me back to Quito over two days—but wait! I recalled some loose change in my panniers, and later, in my cabin, I unpacked my gear and liberated 67 cents. Such money can buy days’ worth of bananas in Ecuador. I felt renewed and secure. I lay on the floor, set up the cook stove and started dinner. I spread out my map and, from Cotopaxi to Quilotoa to Baños to the Amazon, I remembered the journey. After all, there was little left to look forward to. I had two days left until my airplane took off.

Dawn arrived in a grim shawl of fog and rain. I hurried through the dripping trees to the restaurant and spent $2, and three hours, drinking coffee. $2.67 cents until Quito. If I camped in Cayambe-Coca that night, I would have to pay nothing—but I had heard from a ranger that the campsite, at roughly 13,600 feet, had no shelter or refuge. “Aire libre,” he told me. Open air. It would be freezing—and wet. I rode uphill and stopped at the same summit I’d crossed the day before. The rain showed no sign of relenting. The turnoff to the park campground was a road of mud and rock, and it disappeared uphill into the freezing mist. I said goodbye to the mountains and pushed ahead. The highway tilted forward, and away I went, downhill at 30 miles per hour.

There was no satisfaction in replenishing my wallet at an ATM in the suburban town of El Quinche. As that machine sputtered and spat out a wad of crisp twenties, the sweetness of the past two weeks seemed to melt away like ice cream dropped in the gutter. I had spent those days searching for food and places to sleep amid incredible scenery. It had been a frugal–but pure and gratifying–way to spend a vacation. Now, with money again, there was no effort, no hardship and no reward in my activity. With an acute sense of disgust, I paid $13 for a hotel room. I would not shiver at night here, and no animals would tromp about in the darkness. I would soon forget this hotel and this lazy town, and I would think nothing of them 24 hours later while I gazed out the window of the airplane upon the wilderness areas of the Andes, at the cold and rocky high country where money is often worthless, and every day and night priceless.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)