This Virginia Winery Once Housed One of WWII’s Most Important Spy Stations

Speakeasies are so 2012—this place has actual secrets

In 1942, the United States Army set up a secret monitoring facility in a farmhouse in Warrenton, Virginia. The farm's relative proximity to the U.S. Signaling Intelligence Service's headquarters in Arlington, VA, combined with the location's isolation and quiet electromagnetic geology, made it a good place to pick up international radio signals. Since World War II was on at the time, the Army bought the land and turned it into a surveillance and decoding base known as Vint Hill Farm Station, or Monitoring Station No. 1. The barn that the Army once used is still there today, but modern visitors won’t need a security clearance to get in—just their photo IDs if they want to get a drink.

Vint Hill Craft Winery is one of the relatively new tenants that have moved into the former spy station, which, until the 1990s, was alternately used by the Army, the CIA and the NSA. Its neighbors include The Covert Cafe, a local brewery, and an inn that offers Cold War-themed escape rooms. Right next door to the winery is The Cold War Museum, a hidden gem of a building, the size of which belies the overwhelming breadth of its collection.

According to the winery’s owner, Chris Pearmund, the Economic Development Administration (EDA) approached him in 2008 about opening a winery there in order to help the area transition from its spy station roots into a place for private use. Sitting on the top floor of his winery, he explains that at the time, “this building was not good for much of anything. It was an old office building in an old barn.” So Pearmund and his team “de-officed it and brought it back to the original barn.” They also dug holes to power the winery with geothermal energy.

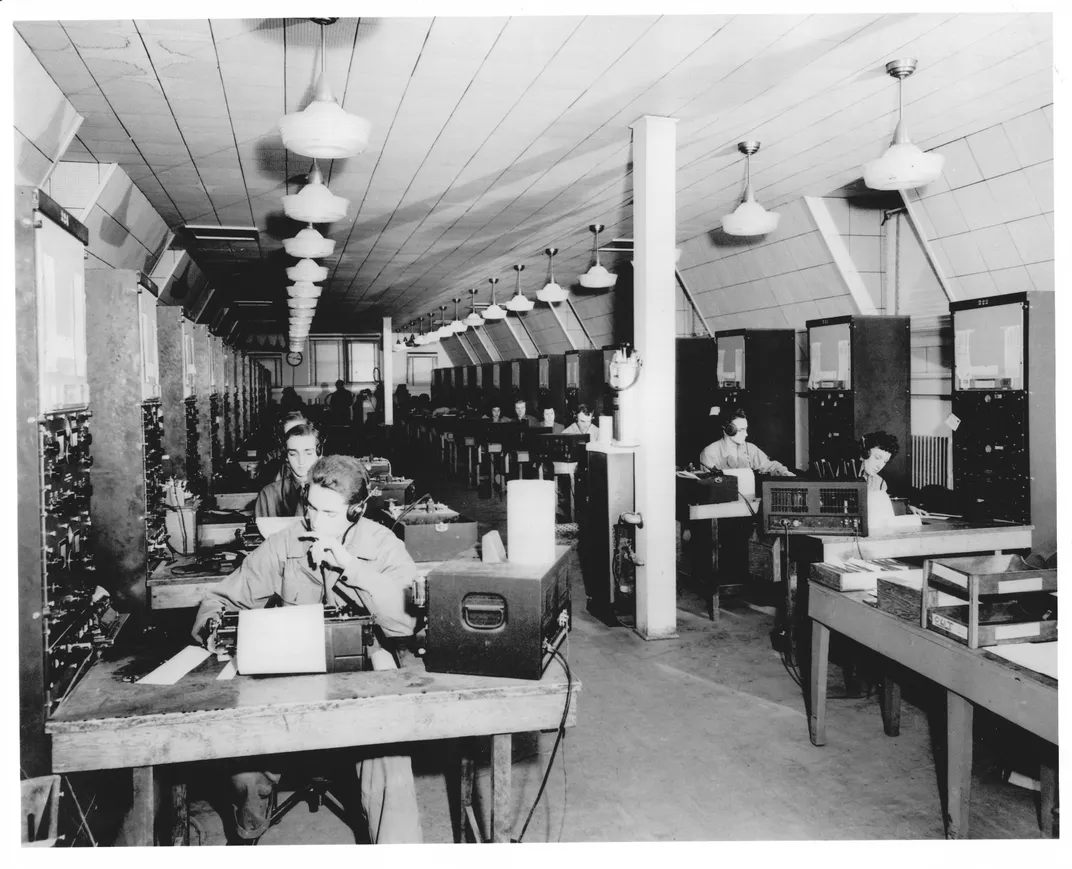

At first, Pearmund wasn’t sure that the area would draw visitors because it doesn’t have the typical picturesque, rolling-hill topography that other Virginia wineries do. But the business has been successful so far, and its unique history might be part of the draw. The winery plays off its past with wine names like “Enigma;” and in the top-floor tasting room, you can examine a photo of WWII spies intercepting morse code taken in the very same room in which you’re sipping wine.

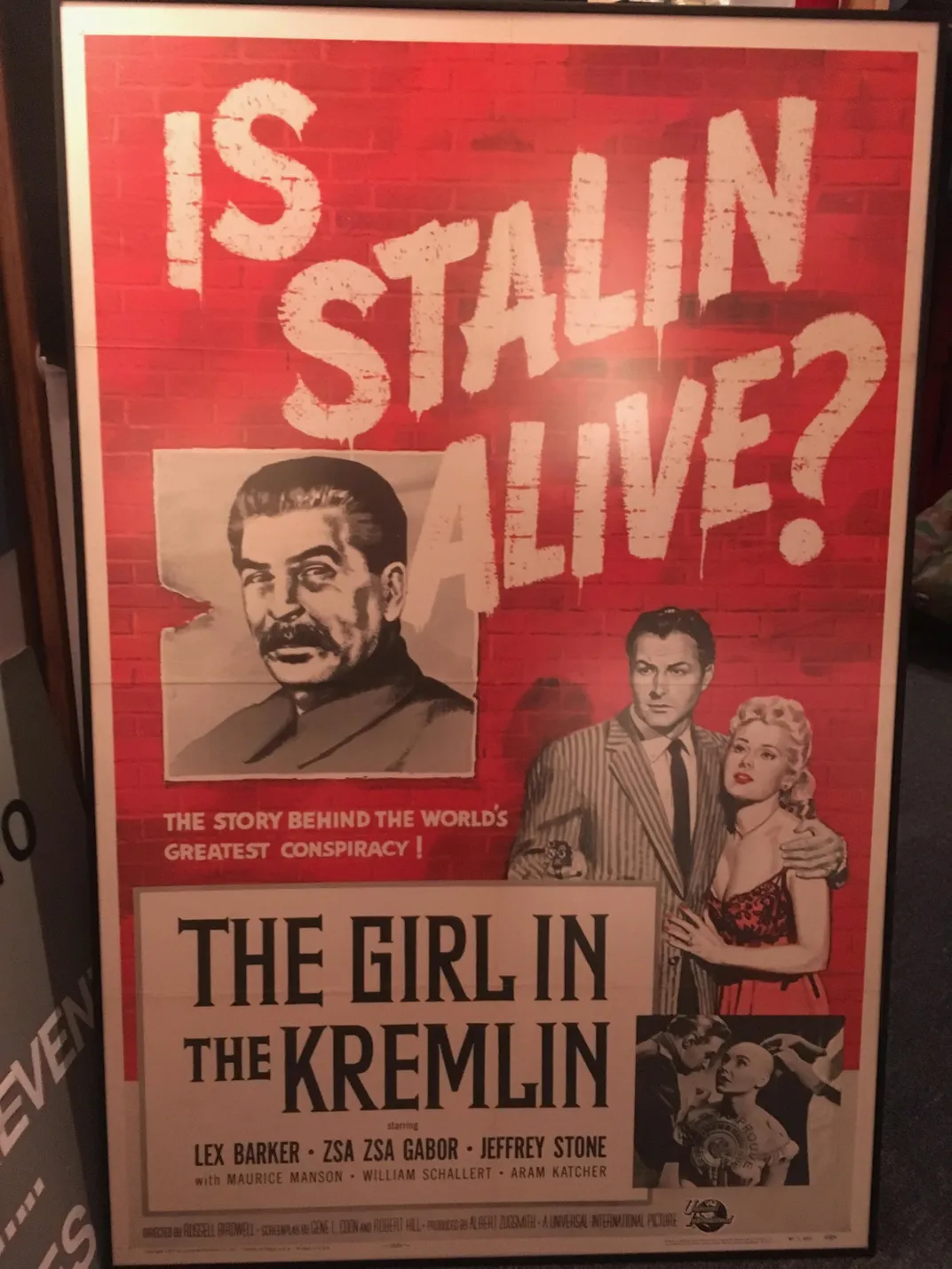

Looking at that mysterious image may very well pique your curiosity about visiting the Cold War Museum next door. The museum was co-founded by Francis Gary Powers, Jr., son of the famed U-2 pilot who was shot down and captured by the Soviets in 1960. Inside, the two-floor museum is jam-packed with surveillance equipment, propaganda posters and a mixture of U.S., German, and Soviet uniforms (the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., has even borrowed items from this collection). The large volume of artifacts and images available to peruse can be overwhelming, but the museum volunteers—many of whom used to work for the military or in national security— are happy to offer tours to help provide context and make sense of it all.

Even though the Cold War is the museum’s main focus, its timeline starts with Vint Hill’s WWII surveillance. During that time, one of the station’s biggest achievements was its interception of a 20-page morse code message from Baron Oshima, the Japanese ambassador to Germany. It revealed information about Germany’s fortifications as well as the location where the Nazis expected the Allies to attack next. With this, the Allies were able to misdirect the Nazis so they could storm the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944—D-Day.

The museum’s Cold War exhibits cover topics with which visitors will likely be familiar, such as the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Berlin Wall (the museum has a small piece). Yet the most interesting ones are about lesser-known events. Near the front of the museum hangs the jacket of an American PB4Y-2 Privateer pilot who was shot down by Soviets and presumed dead. It was donated by his wife, who learned years after the event that he had been imprisoned by the Soviets and had likely died in jail.

The museum’s executive director, Jason Hall, says he thinks it’s important that the public know about events like this. “Even when we were not in a hot war,” he said, “there were people who got killed.”

There’s also a display about one of the Cold War’s little-known heroes, Vasili Arkhipov. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, he is credited with convincing a Soviet submarine captain not to take out American ships with a 15-kiloton nuclear torpedo. The attack would have prompted a retaliation from the United States, and then from the Soviet Union, leading to the terrifying possibility of mutual assured destruction.

“If it were not for him, it would’ve been World War III, no question,” Hall explains.

The museum’s aesthetic is relatively DIY—most of the displays are labeled with computer print-outs pasted on black construction paper. Entry is free, but the museum also hosts paid events, like an upcoming presentation on March 19 by former NSA and CIA director General Michael Hayden and his wife Jeanine, who also worked at the NSA. These events are usually held in collaboration with the neighboring winery or brewery.

Hall says that the cooperation between the new tenants of the former spy station is making the area “a kind of a history destination.” He hopes that attracting visitors to the area will encourage people to ask themselves larger questions about the Cold War and the United States’ relationship to Russia—questions that he feels are still relevant to our lives today.

“Why would you not want to think about our relations with Russia,” he asks, “given what Putie’s been doing?” And while you ponder that here, you can wander up to the bar to order another glass of wine.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.