Colombia Dispatch 10: Education for Demobilized Forces

In exchange for laying down their arms, soldiers from Medellin’s armed militias are receiving a free education, paid for by the government

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/des_631.jpg)

The fifth-grade class in downtown Medellin was unlike any I had ever seen. In front of the young female teacher sat about 13 men in their 20s and 30s, all formerly guerrilla or paramilitary soldiers in Colombia's long-running conflict. As part of peace agreements, they turned in their arms to the government in exchange for amnesty and an education.

"What do you plan on doing when you finish school?" I ask the class.

"What, when I grow up?" says one man of about 30, to general laughter. He explained that he had been taking woodworking classes on the weekend. "After getting out of here I can hopefully be somebody in life."

Statistics show that more than 80 percent of the demobilized soldiers in Medellin never finished high school. About 10 percent are functionally illiterate, and many were never eager to join illegal armed groups. About half of Medellin's demobilized soldiers say they entered illegal armed groups out of either economic necessity or because of threats against their life. With little options for work and living in areas where violence was an everyday occurrence, they signed up for steady food and the protection of an armed group.

When the government signed agreements in late 2003 that demobilized many of the soldiers in Medellin's illegal armed groups, it was faced with the problem of what to do with thousands of unskilled, uneducated young men. To keep them from going straight into gangs, the government offered demobilized soldiers a way out. They receive a monthly wage from the government to finish school, completing one grade every three months, attend workshops that teach work and life skills and are also given access to therapy and counseling.

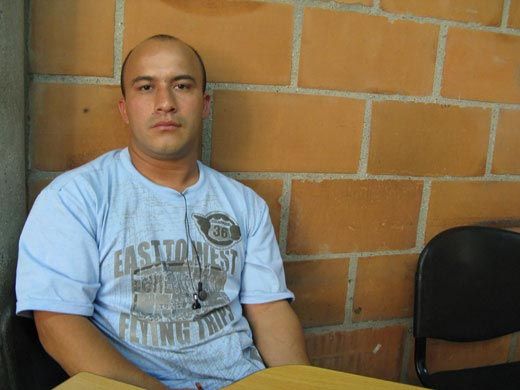

I sit down to talk with Juan Guillermo Caro, 28, after his first-grade class at the Center for Peace and Reconciliation, where he is learning how to read and write. His mother left him as a boy in his rural village to stay with a woman who he paid through his work cutting sugarcane and carrying loads. He never had much time to go to school. He signed up for a paramilitary branch called "Grupo Occidente" as an unemployed young man, hearing it was regular work defending the town from other violent groups. But Caro was happy to hear the call for demobilization a few months after he started. "That is not a life," he says. "I never have liked war."

Colombia's peace process may prove a valuable example for other parts of the world experiencing insurgencies and civil conflict. Jorge Gaviria, director of Medellin's peace and reconciliation program, says that reintegrating the roughly 5,000 demobilized soldiers he works with into society is key to breaking the cycle of violence that has defined Medellin for years.

"We have to make a place for them, open our hearts and find a reason for their inclusion into society," he says. "If we don't, this will repeat and will repeat."

As part of the reconciliation process, the program connects victims of the war's violence with its former perpetrators. "They're the same as us," Gaviria says, pointing to the photographs in his office, including one of smiling young men in chefs' uniforms cooking at a community event; demobilized soldiers serving victims. "Look at the pictures. There they are, in their neighborhood, with their friends, everyday life, returning to society. We are trying to make sure they stay there."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.