Colombia Dispatch 6: Accordion Rock Stars in Valledupar

Andres ‘Turco’ Gil’s accordion academy trains young children in the music of vallenato, the folk music popular across Latin America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/vallenato_631.jpg)

The small city of Valledupar is famous as the birthplace of vallenato, an upbeat accordion-driven folk music that plays constantly in streets, shops, buses and restaurants across northern Colombia and has become popular across Latin America. I came to the clean, quiet streets of the city, an off-the beaten corner of the country near the Venezuelan border, to follow up on an article I wrote for Smithsonian's June issue on vallenato music.

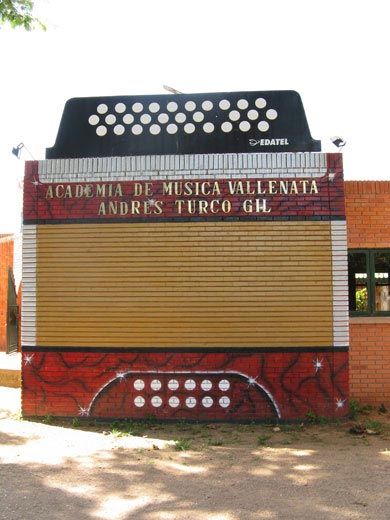

Children here dream of being accordion stars the same way kids in America practice guitar hoping to become rock stars. With that in mind, I head out to Andres "Turco" Gil's accordion academy on the outskirts of the city. The young children at Gil's academy have played around the world as part of the Vallenato Children band, and count both Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and Bill Clinton among their fans. Many win prizes at the annual vallenato festival held in Valledupar.

But Gil isn't just looking for fame. "A child who plays accordion or other instrument doesn't pick up a gun," he says, noting that the countryside around the academy has been heavily affected by the country's violent conflict.

"The music makes them noble, it changes their heart. They start to sing, they forget about their problems and they feel happy."

Gil has about 1,000 students sharing 60 accordions, and he says that about 80 percent are refugees from violence or live in poverty. They attend the school for free, supported by donations, earnings from concerts, and tuition from wealthier students who come from as far away as Europe, Mexico and the United States to study with the accordion master.

The students range in age from three-years old to senior citizens, though the majority ranges between 6 and 15 years of age. The best students practice at the academy for hours after school and after only a year or two of study will perform in Colombia's vallenato music competitions and with the Vallenato Children band.

The students "show a different side of our country," Gil, soft spoken and gentle, tells me as children practice accordion in the brick courtyard of his school. "Colombia isn't just corruption and drug trafficking and violence. We have very strong culture in our Vallenato music."

The school started small more than 20 years ago when parents brought their children to Gil's home to learn from the well-regarded accordionist. With the aid of his 18 children (most of whom are named Andres or Andrea, after their father) Gil taught the ever-increasing number of students, renting a small house and finally moving into the tidy academy, a brick building with an accordion façade, 6 years ago.

After a short chat with Gil in his office, he runs off to fetch his new star student. He introduces me to 9-year-old Juan David Atencia, a plucky blind boy who lives with his grandmother in a city four hours away and started playing accordion just a year ago. Gil is so struck by the student that he pays for the taxi that brings Juan to Valledupar every Monday and returns him to his grandmother Friday evenings. In the meantime Juan stays at Gil's house and plays accordion at the academy all day because Gil says there is no school available for blind students in the area.

As soon as Juan straps the accordion on his chest he starts playing a fast song, head swaying back and forth and a huge smile on his face. Two grown men step into the room and back him up on percussion. Juan sings at the top of his lungs and stomps his foot in time as Gil sings backup and shouts encouragement. Juan soon breaks into one of his own compositions, singing, "I'm a little blind boy, but I can see with my accordion."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.