How Brussels Became a Real-Life Comic Strip

The city’s colorful murals put it in the running for comic book capital of the world

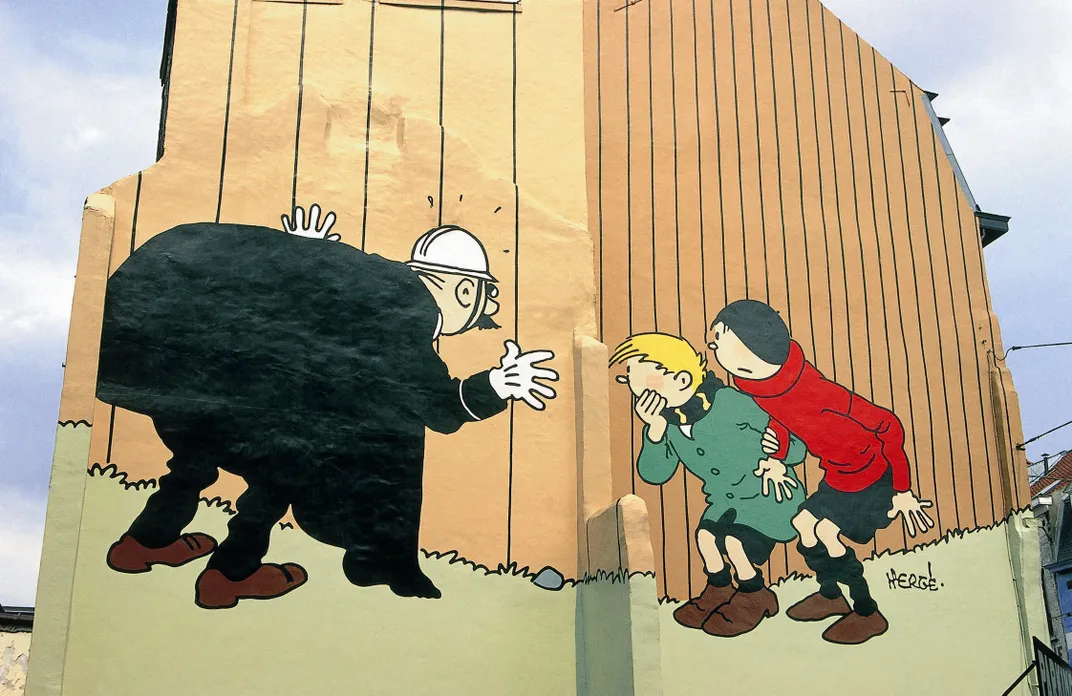

Along Rue de l’etuve, a narrow street in Brussels, a sea captain hustles down a building’s fire escape, trailed by a young reporter and his dog. If the trio look frozen in time, it’s because they are—they’re part of a mural that’s recognizable to anyone who has ever read a Tintin comic.

Walking through Brussels is a lot like flipping through the pages of a comic book. Around practically every corner of Belgium’s capital, comic book characters spring to life on colorful murals on the exterior walls of houses, boutiques and blank “canvases.” They’re all part of the city’s Comic Book Route—just one of the things that makes Brussels a paradise for comic book lovers.

The route began in 1991 when the city and the Belgian Comic Strip Center, a museum dedicated entirely to comics, commissioned local author Frank Pé to sketch an original piece featuring characters from his popular Broussaille and Zoo series. The result was a 380-square-foot showpiece on the side of a building located at one of Brussels’ busiest intersections. Citizens asked for more, so the city commissioned dozens of local comic book authors to create original murals to give a splash of color to the city’s streetscapes. Today, more than 55 murals make up the route, and the city plans to add even more in the future.

Comic books have always held a special place in the hearts of Belgians, but it was artist Georges Remi, who went by the penname Hergé, who really helped popularize comic strips, which are known as “the ninth art” in French-speaking circles. In 1929, Hergé introduced the series The Adventures of Tintin about a young Belgian reporter and his trusty dog, and the Franco-Belgian comic strip was born. In the years since, more than 230 million copies of the series have been sold in some 70 languages and there’s even a museum outside of the city dedicated to his work. Hergé’s overnight success spurred an interest in comics in Belgians of all ages, inspiring many to put pen to paper and create characters of their own. After World War II, comic strips became as common in newspapers as want ads.

“Comic strips are very popular in Brussels and Belgium because every child has grown up with comic strip characters like Tintin, the Smurfs, and Spirou,” Emmanuelle Osselaer, who works in the arts and creativity department of Visit Brussels, tells Smithsonian.com “The Comic Strip Route is a living thing, and every year some of the murals disappear while others come into being.”

One Belgian child in particular grew up to become one of the city’s most celebrated authors. From a young age, Marnix “Nix” Verduyn, the creator of the popular Kinky & Cosy comic strip and TV show, knew he was destined to draw comics.

“When I was six or seven years old there was another boy in my neighborhood who also made comics,” Nix tells Smithsonian.com. “Every day we would each create one page of the comic book and then swap. I remember I would run to my mailbox several times a day to see if he delivered it so that I could start on the next page.”

Later this spring, Nix will get his first mural on the side of a healthcare services building just steps away from Rue de la Bourse—also known as Kinky & Cosy Street—a narrow artery that runs through the heart of the city. (Yes, Brussels also uses the titles of comic books as secondary names for many of its roadways.)

So why is this city such a draw for comic book artists in the first place? Ans Persoons, a city alderwoman who is part of the committee that decides which comic books will get murals, thinks it comes down to economics.

“People move to Brussels to work on their comics since the cost of living is more affordable than other European cities,” Persoons tells Smithsonian.com. “There’s also a strong tradition here to keep our city’s comic book culture alive.” That tradition includes numerous cafes, shops and other attractions dedicated to the art. The murals have other benefits, too: Persoons says that the murals are a way to invest in and help bring together communities, many of whom embrace the new art as a kind of local landmark and point of neighborhood pride.

Now that the majority of the city’s most recognizable authors have received murals, Persoons is shifting her focus to a younger, more diverse set of authors. “Right now I’m coming up with some new ideas for the route that will include the younger generation of authors coming up, especially authors of graphic novels,” she says.

Her selections will likely include more women, too. Although at one time men were the majority of comic book authors, that’s no longer the case. Diversity in comics has become a lightning rod internationally, but especially in the French-speaking world: Earlier this year, when the Angoulême International Comics Festival released the names of the 30 authors in the running for the coveted Grand Prix d’Angouleme award, ten of the nominees boycotted by withdrawing their names from the list after noticing that no women were included.

Persoons hopes that by honoring up-and-coming comic book artists, she can help future generations embrace the art form like Belgians do today. “Comics are a form of art that’s accessible to everyone,” she says—a directive the city seems destined to take literally for years to come.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/06/b606865d-943b-405f-ade4-de8bf09da51b/42-38528318.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/40/5940219e-5730-4ddc-a29d-3df3c532afc7/42-77254470.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/df/36dfd457-a9ab-4c42-958e-72586aab86b0/mur_bande_dessinee_corto_maltese.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d8/0b/d80b6d9b-4aff-447c-9e34-d61f70ae92f3/mur_bande_dessinee_le_jeune_albert.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/7b/6e7b629b-162e-45b4-b900-4b3633d6d74f/mur_bande_dessinee_le_scorpion.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/2c/8d2cf80d-ca04-40a4-ae37-0e3b1f35097d/7105495477_1697ff8c64_k.jpg)