The Complicated History of Flamenco in Spain

The music, born of gypsies in the country’s southern regions, was embraced by foreigners long before it became a national symbol

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/23/1c238289-ee9c-40c8-b1b7-dd9af0bf445c/flamenco.jpg)

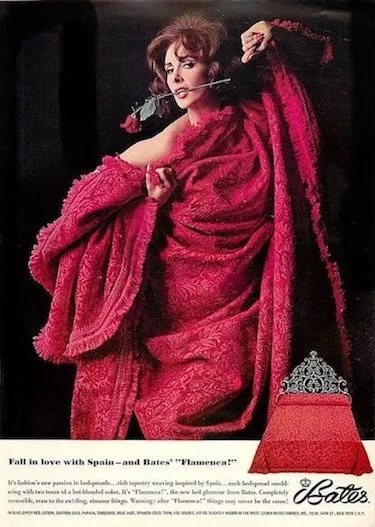

During the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair, an advertisement for the Bates textile company in the Pavilion of Spain’s official guide book featured a fetchingly posed young woman, rose in mouth, with a ruby red bedspread draped over her body to form the likeness of a flamenco dress. The text beckons us to “fall in love with Spain—and Bates’ ‘Flamenca!’” and encourages us to discover “fashion’s new passion in bedspreads … each bedspread smoldering with two tones of a hot-blooded color.”

In the U.S. and elsewhere, flamenco is a pervasive marker of Spanish national identity. For proof of its currency in pop culture, look no further than Toy Story 3: Buzz Lightyear is mistakenly reset in “Spanish mode,” and becomes a passionate Spanish flamenco dancer. Indeed, the world outside Spain often stereotypes the nation as inhabited by flamenco dancers, singers, and guitar players who are so “passionate,” they have little time to engage in the day-to-day world of the mundane.

Inside Spain, however, the relationship between the flamenco art form and Spanish national identity has been fraught for more than a century. Indeed, the world’s love of flamenco has long created problems within Spain, where the performance was once considered a vulgar and pornographic spectacle. Over the years, many Spaniards considered flamenco a scourge of their nation, deploring it as an entertainment that lulled the masses into stupefaction and hampered Spain’s progress toward modernity. Flamenco’s shifting fortunes show how Spain’s complex national identity continues to evolve to this day.

Flamenco, which UNESCO recently recognized as part of the World’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, is a complex art form incorporating poetry, singing (cante), guitar playing (toque), dance (baile), polyrhythmic hand-clapping (palmas), and finger snapping (pitos). It often features the call and response known as jaleo, a form of “hell raising,” involving hand clapping, foot stomping, and audiences’ encouraging shouts. Nobody really knows where the term “flamenco” originated, but all agree that the art form began in southern Spain—Andalusia and Murcia—but was also shaped by musicians and performers in the Caribbean, Latin America, and Europe.

Moreover, from the mid-nineteenth century on, flamenco entertainment spread quickly from southern Spain to the capital (Madrid) and onward to other Spanish urban centers, flourishing there as a consequence of the rise of a mass urban culture and increased foreign tourism.

The reason for flamenco’s horrible reputation among Spanish elites during the 19th and 20th centuries was that historically, performances were associated with the ostracized Gypsy (Roma) population in Spain, and they took place in seedy urban areas.

Spanish elites particularly despised how foreigners linked Spain with flamenco. Spain’s national identity had previously been defined by outsiders who tied the country to Inquisitors, beggars, bandits, bullfighters, Gypsies, and flamenco dancers. Usually foreigners imposed the flamenco identity onto Spain as a backhanded compliment to highlight Spain’s steadfast authenticity. The nation had not fallen prey to the soul-sucking effects of industrialization. But with very few exceptions, Spanish elites and social reformers never liked—nor wanted—this art form to represent themselves or their nation, and they fought flamenco fever with all the resources they could muster. But flamencomania proved much more difficult to eradicate than the so-called Black Legend: the negative propaganda, spread by Spain’s French and British rivals, that characterized Spain as the land of cruel Inquisitors, sadistic colonial rulers, repressive politicians, and intellectual and artistic yokels.

Flamenco came to encapsulate Spanish elites’ feelings of shame about the country’s declining status as a great power in the modern era. Flamenco’s critics were divided into three main groups: the Catholic Church and its conservative allies, left-leaning intellectuals and politicians, and leaders from revolutionary workers’ movements. During the convulsive period between the Restoration and the beginning of the civil war, from 1875 to 1936, these groups used flamenco to critique what they saw as Spain’s political, economic, and cultural ills.

The Catholic Church perceived flamenco as an offshoot of the sort of mass cultural entertainments that led to immodesty, the breakdown of the family, and the weakening of the Patria. But for many progressive intellectuals, by contrast, flamenco—along with its twin scourge, bullfighting—was thought to keep Spaniards in a stranglehold of backwardness. They saw the entertainment as a distraction that prevented Spaniards from solving the nation’s numerous ills, including a corrupt political system, a wildly inadequate and unequal educational system, a lack of infrastructure and technological know-how, and vast inequalities of wealth. Meanwhile, for working-class reformers and revolutionaries, flamenco and its concomitant lifestyle exploited people’s poverty and diverted workers away from becoming full actors in seeking revolution to end social, political, and economic inequality.

In reality, all of these groups used flamenco as a vessel to contain their dissatisfaction with the ideological and structural changes that emerged out of the French and Industrial Revolutions. They railed in newspaper diatribes against this form of entertainment, with some critics seeing flamenco as the perverted outcome of increased secularization, while others thought it showed resistance to progress and modernization. What they were really complaining about, however, was the permeation of modern mass culture into the daily lives of everyday citizens.

The many World’s Fairs of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries gave flamenco a boost, making Spanish Gypsy performers all the rage, especially in Paris. Flamenco “deep song” (cante jondo) received the blessings of European avant-garde artists such as Sergei Diaghilev and Claude Debussy, who had attended flamenco performances at the Paris World’s Fairs of 1889 and 1900, and found it primal and authentic. That led Spanish intellectuals and artists such as Manuel de Falla and Federico García Lorca to elevate this form of flamenco to “high culture.” Thus, the support of Europeans outside Spain transformed the cultural meaning of flamenco for Spanish artists and intellectuals in much the same way that 20th-century European support for African-American jazz and blues aided their popularity in the United States.

But after the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War, from 1936 to 1939, flamenco performances in Spain diminished considerably. The Catholic Church and leaders of the Sección Femenina (the female wing of Spain’s Fascist Party) disavowed flamenco. To counteract its perceived evils, they promoted folk dancing and singing, encouraging a new kind of national identity predicated on Spanish regional diversity and cleansed of flamenco’s torrid reputation.

But by the 1950s, after years of international isolation, the Franco regime needed money. This led the regime to change course, promoting flamenco in order to jump-start Spain’s tourist industry. A tourism promoter named Carlos González Cuesta wrote, “We have to resign ourselves touristically to be a country of [Spanish stereotypes], because the day we lose the [Spanish stereotypes], we will have lost 90 percent of our attraction for tourists.”

So the Franco regime pandered to tourists’ love of flamenco, increasing the number of clubs that specialized in it, advertising female flamenco dancers on tourism and airline brochures, encouraging professional flamenco performers to star in Hollywood films, and featuring performers in traveling exhibitions like the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. These strategies worked; the regime was able to bring in millions of tourists and their money to help fund Spain’s economic boom of the 1960s.

After Franco’s death in 1975, the role of flamenco once again changed dramatically. The nearly simultaneous movements for regional autonomy within Spain and the growth of a world music culture complicated flamenco’s relationship to Spanish national identity. The foreign depiction of Spain as the land of flamenco, the not-quite European country with the Oriental-Gypsy soul, has been exploited by entrepreneurial spirits within Spain. That is not to say that flamenco flourishes today only to serve the interests of commerce. Artists, scholars, and historical preservationists have chosen to undertake serious study of the art form and to promote its historical and artistic significance for both Spain and Andalusia. In fact, one could say that flamenco today has undergone both extreme commercialization and renewed artistic and academic respect, once again demonstrating its complex relationship to Spanish national identity.

Sandie Holguín is a professor of history at the University of Oklahoma. Her most recent book is Flamenco Nation: The Construction of Spanish National Identity.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.