How Chuck Taylor Taught America How to Play Basketball

A shoe-in for the first ever basketball game in the Olympics, Converse All Stars have a long history both in and out of sport

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/36/163617e5-ebe2-452b-b475-36a5154e8959/chuck-taylor-all-star-circa-1957.jpg)

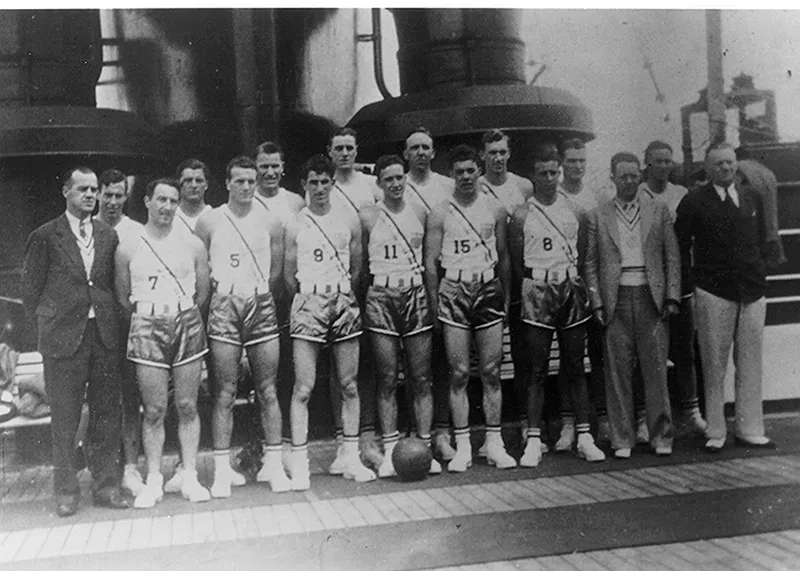

It was 1936, and the United States men’s basketball team stepped onto the rain-soaked outdoor courts sporting bright white Converse shoes—patriotic blue and red pinstripes wrapping around each sole. The Americans were taking on the Canadians in the Olympic finals, and the conditions were miserable. As it poured, water inundated the courts, turning them into a “sea of mud,” according to the New York Times. But, in a painfully low-scoring game, the U.S. ultimately won 19-8.

This was basketball’s inaugural year in the games and the first of seven consecutive Olympic gold medals for the U.S. men’s team. But it also marked the first appearance of the iconic “Olympic white” Chuck Taylor shoes—a design still around to this day.

The history of the shoe is nearly as old as the game of basketball itself, and in a way both matured together. In 1891, YMCA physical educator James Naismith invented the indoor game, played with a soccer ball and two peach baskets, to keep his students fit during the frigid Massachusetts winters. Seventeen years later, Marquis Converse founded his Converse Rubber Shoe Company, also in Massachusetts, to produce rubber galoshes, a far cry from the canvas kicks the company is known for today.

The company churned out these protective boots for the wet spring, winter and fall, but sales inevitably dropped during the dry summer months. After two years of Converse firing his employees at the beginning of the slump and rehiring when the rains returned in autumn, the entrepreneur made a bid to keep his most skilled workers year-round. He started making a non-skid, canvas-topped shoe.

The first version was a low-top oxford kind of shoe, says Sam Smallidge, the head archivist at Converse. But these dressy sneaks quickly became associated with sports, specifically the rapidly spreading basketball craze. In 1922, the Converse Rubber Company hired a charismatic athlete named Charles “Chuck” Taylor as part salesman, part player-coach for the shoe’s club team, the Converse All Stars.

“It was all about promotion,” says Abraham Aamidor, author of the book Chuck Taylor, All Star. “The team was not in a league, but would travel through small Midwestern towns and challenge the local hot shots to a game.”

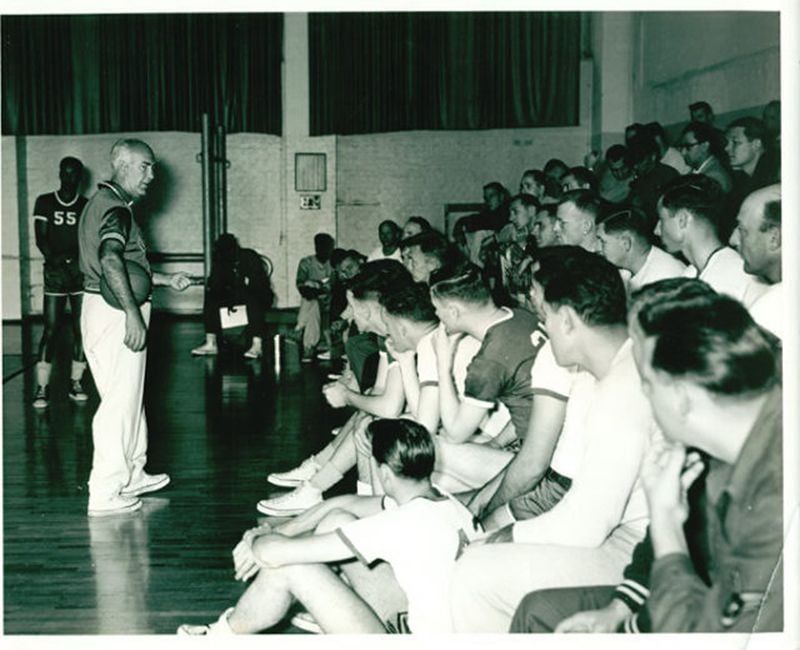

By Aamidor’s count, the All Stars played about 30 games a year. In addition to these games, Taylor hosted clinics to teach people the relatively new sport. Sporting goods stores sent representatives to the clinics to sell Converse All Star shoes to the captive audience—touting the kicks as the best basketball shoes around.

“What Converse was doing was teaching America to play basketball,” says Smallidge. But in addition to this, these clinics “allowed Converse to cement this relationship with basketball itself as being the premiere basketball shoe.”

The clinics would often include a basketball game and a sideshow featuring Chuck and free-throw fiend Harold “Bunny” Levitt, according to Aamidor. “Chuck did his trick shots and Bunny Levitt never missed a free throw,” he says. The duo would then pass out pocket-sized instruction books on how to play the game.

Taylor traveled all over the country hosting clinics and promoting the shoes. Shoe sales were booming, but all was not well with the company. In the mid-1910s, competing rubber companies ventured into the production of rubber galoshes, which were still a Converse classic. So Marquis Converse tried to edge in on the competition’s money-maker: rubber tires.

At the time, tires were a rapidly changing technology, and Converse couldn’t keep pace. The Great Depression only added to the company’s troubles, says Smallidge. “He sunk so much of his money into this tire business, so when the tire business collapsed, it kind of dragged the rest of the company down with it,” he says. In 1929 Marquis Converse lost the company.

The business changed hands several times. Hodgman Company had a brief stint, but its president died in a freak hunting accident soon after the merge, says Smallidge. Businessmen Joseph, Harry and Dewey Stone bought the floundering company in 1932.

“The Converse name had lost its glitter,” says Aamidor. "The company was in trouble.”

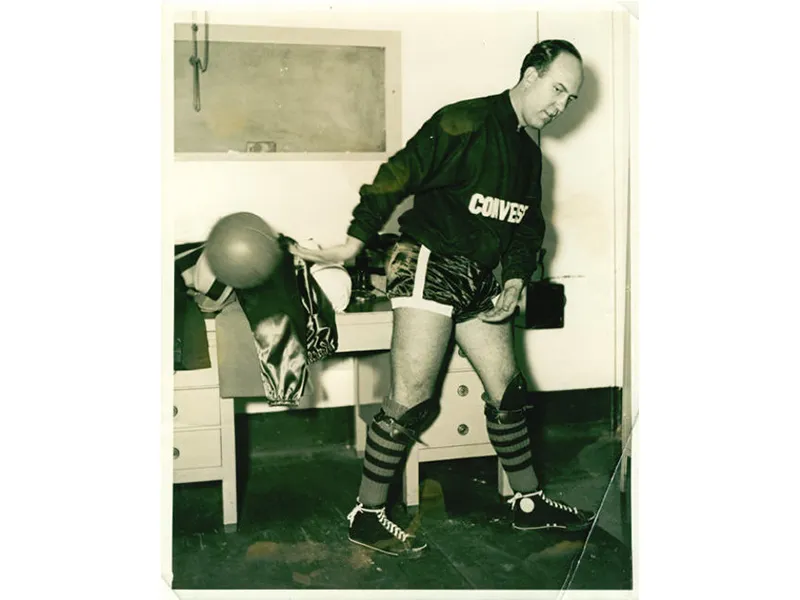

Taylor, then the company’s sales manager, decided to market himself as a great basketball player and add his name to the shoe, Aamidor explains.

“He neither was a great player, nor did he play on some of the great teams that he said he played on,” says Aamidor. But he did have moderate abilities with basketball and the connections in the field to make an impact. Though many—if not all—basketball coaches knew “it was a bunch of hooey,” he says, they accepted the act and moved on.

Taylor signed a contract with Converse to add his name in 1933, and the change went into effect the following year, says Smallidge. The All Star became the Chuck Taylor All Star.

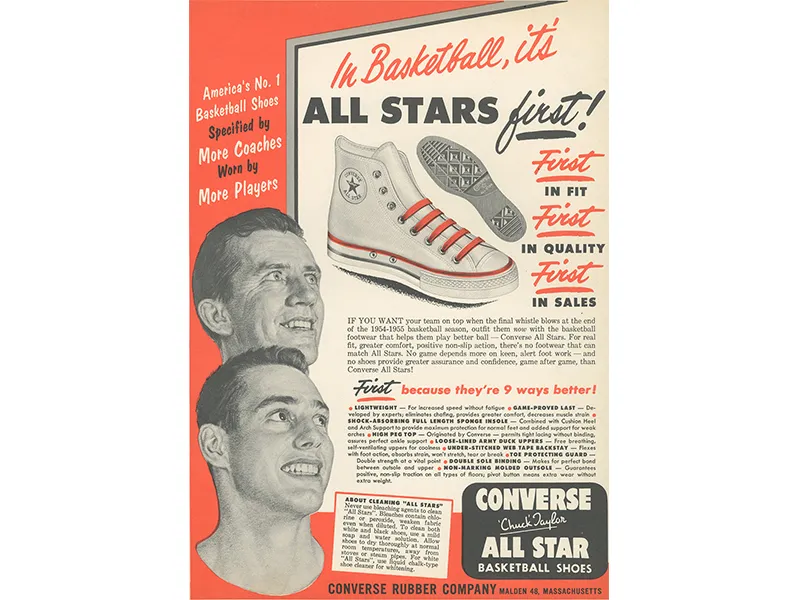

As Taylor’s popularity and infamy as a big-shot basketball player grew, he continued to work the road selling shoes. It was his personal touches as a salesman that made all the difference, says Aamidor. For big college tournaments, Taylor often attended himself to support the teams and care for the shoes. If there were problems with stitching, fit or damages, Taylor was on hand to make the repair.

“This would be like buying a basketball that has a Lebron James signature on it,” says Aamidor, “and when you want to get it inflated to the right pressure, there's Lebron James doing it for you.”

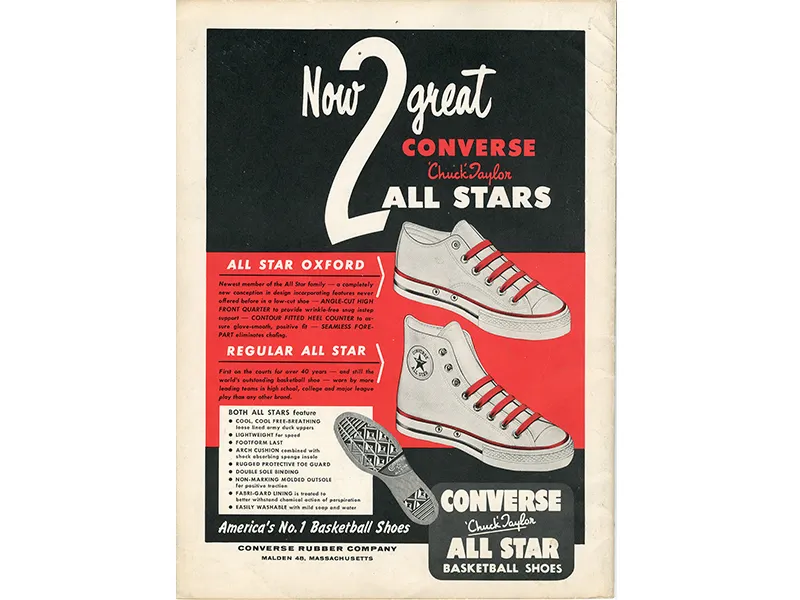

Similar to today, what people wore in large part came down to marketing. “Chucks weren't the only canvas shoes with rubber bottoms,” says Aamidor. Other shoe manufacturers at the time, such as Spalding and BF Goodrich, had similar options. "But they [Chucks] were the most expensive ones and the most elite ones,” he adds.

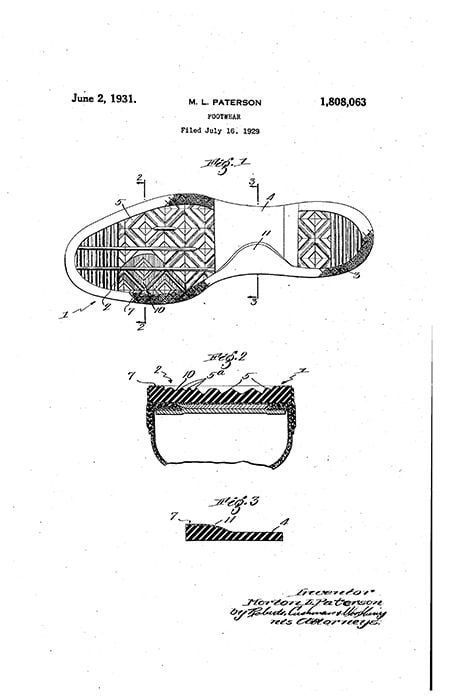

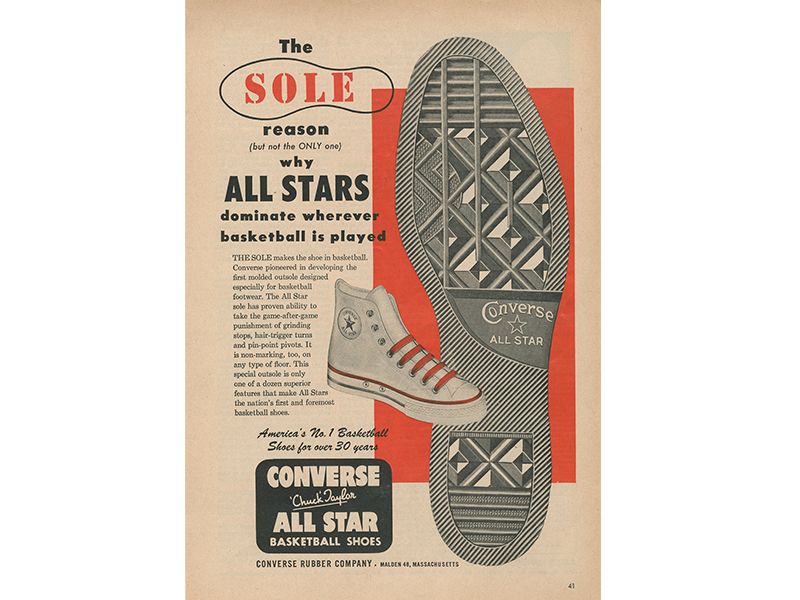

Converse’s ultimate goal was to make shoes with the grippiest soles around. The tread pattern became fixed in the mid-1930s, and the patented design is still used in today’s Chucks.

When the first Olympic team formed in 1936, and needed team sneaks, the company was a shoe-in. Converse debuted the “Olympic White All Stars” that year—a departure from the traditional black high tops.

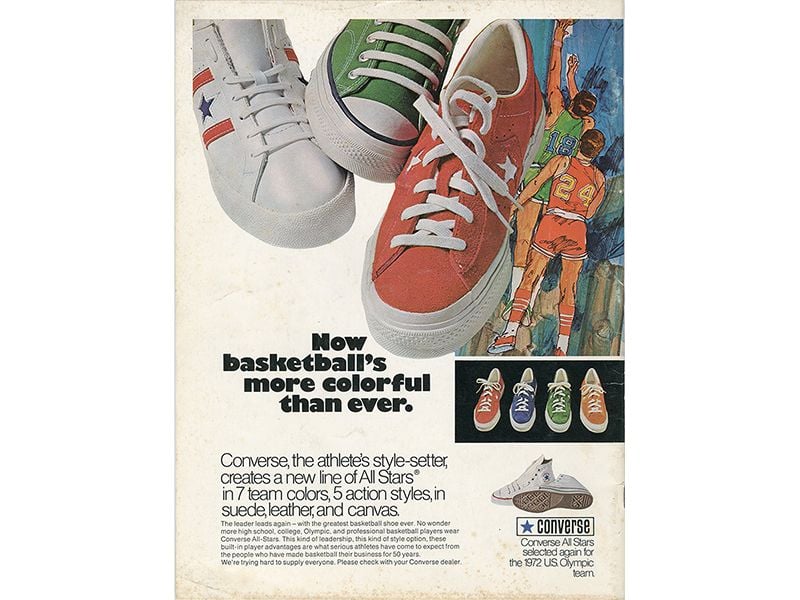

The shoe remained the Olympic shoe of choice for decades, but its popularity in sports began to peter out in the 1970s when players started expecting lucrative endorsement contracts. Converse didn’t pay athletes to wear their products until 1975, when they gave Julius “Dr. J” Erving an endorsement deal. But even then, the company just couldn’t keep pace with the massive deals and clothing lines that other companies began offering their players.

The 1984 games was Converse’s Olympic swan song. The company was the official footwear sponsor of the games, and the U.S. men’s basketball team won gold sporting Converse’s latest leather sneaks.

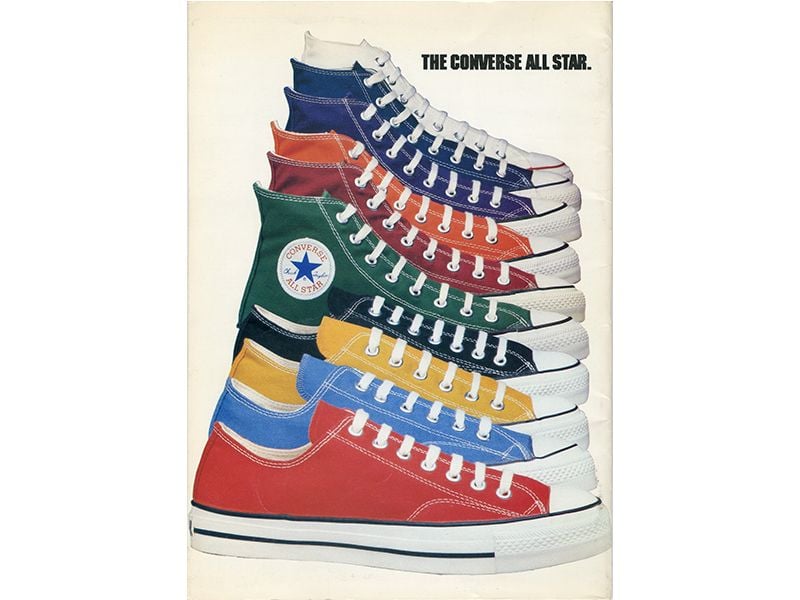

Even so, paralleling the company’s popularity decline in the professional sports world was a growing following in rock culture. The introduction of seven colors of the shoe in 1971 bolstered this movement, and shoe sales pivoted from the courts to the streets.

“Really it's the only clothing that you'll ever see old men, young girls, hipsters in New York, [all wearing],” says Aamidor, of Converse’s now broad appeal. “Anybody is likely to be wearing those shoes.”

These days, Chuck Taylor—the man—has been lost somewhere in history. He was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1969, and died later that year. He is no longer remembered in his invented persona of a basketball star or as a spectacular salesman. Many people even assume the name is like Betty Crocker, says Aamidor—a brand name only.

But Taylor was indeed flesh and blood. His love of basketball and Converse shoes helped build the sport into a classic American game.

Chuck Taylor, All Star: The True Story of the Man behind the Most Famous Athletic Shoe in History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)