Continental Crossroads

East greets West as Hungary’s history-rich capital embraces the future

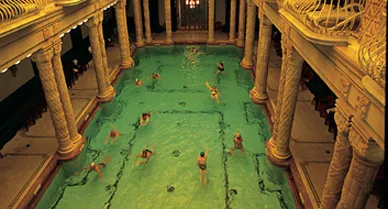

At the nearly century-old Gellert Hotel, site of a venerable spa on the west bank of the Danube, a dip into a steaming mineral bath makes a fitting start for soaking up the spirit of Budapest, Hungary's beguiling capital. The Gellert's cavernous, Art Nouveau spa first opened its doors in 1918, the year Hungary became an independent nation, after the Austro-Hungarian Empire was dissolved in the wake of World War I. The sulfurous, spring-fed baths under barrel-vaulted ceilings hark back to an ancient tradition: the Romans were first drawn to this Central European plain around A.D. 50 by the prospect of curative waters. They also hint at the city's multilayered past. Turquoise tiles and ornately carved columns evoke the Turkish Ottoman occupation (1541-1686), and Baroque-style cherubs on the walls are a salute to Austrian Hapsburg rule (1686-1918).

Hungarian, the language spoken by my fellow bathers—business executives, politicians and pensioners—is rooted in a linguistic strain introduced around A.D. 900 by Magyar nomads from western Siberia. It shares similarities with only Finnish and Estonian and has long functioned as something of a bulwark against foreign domination. "It was very important in maintaining our national identity," says Andras Gero, the preeminent historian of Budapest. "Turks, Austrians, Germans and, more recently, Russians never could learn Hungarian."

From the Royal Palace, begun in the 1200s and later rebuilt in styles ranging from medieval to Baroque, to the 1859 onion-domed Great Synagogue in the former Jewish quarter at the heart of the city to the neo-Gothic 1905 Parliament, Budapest's eclectic architecture and narrow, winding streets may recall Old Europe. But the dynamism is definitely New Europe. Since Communism's fall in 1989, the pace of change on either side of the Danube—Buda on the west and Pest on the east—has been extraordinary. The city of two million is now rich with risk-taking and democracy, and the most prominent figures in politics, business and the arts seem to be uniformly young, ambitious and impatient.

"Under Communism, somebody was always managing your life, and it was quite easy to become passive," says Zsolt Hernadi. As chairman of the oil and gas conglomerate MOL, Hernadi, 45, has presided over the metamorphosis of this formerly state-owned behemoth into the country's largest private corporation. He has fired a great many employees, including 80 percent of the firm's 50 most senior managers. "Age isn't my criterion," he insists, "but frankly, I find that people who are in their 30s and 40s are more willing to move in new directions."

The new spirit is mirrored in the physical transformation of Budapest itself. City historian Andras Torok, 51, published his now-classic Budapest: A Critical Guide in 1989. "My ambition was to reveal everything about Budapest," he tells me. But no sooner had his guidebook appeared than readers began pointing out omissions—the renovated lobby of an old building, a restored statue, a new row of shops. Since then, Torok has had to update the guide five times.

At the same time, old traditions are being revived. In the early 20th century, the city boasted more than 800 coffeehouses. "Intellectuals couldn't [afford] to entertain or even keep warm in their own apartments," says Torok, but for the price of a cup of coffee, they could spend the better part of a cold winter day in a café, discussing lyric poet Endre Ady (1877-1919) or satirical novelist Kalman Mikszath (1847-1910), or debating the politics of Count Mihaly Karolyi (1875-1955), the nationalist who formed modern Hungary's first government in 1918, and of Bela Kun (1886-1936), the leftist revolutionary who toppled it a year later. During the Communist era (1945-89), coffeehouses, which were deemed likely to attract dissenters, virtually disappeared. But in recent years, a handful of lavish, nostalgic cafés, re-created in early 1900s style, have opened, though they tend to be expensive. The handsome Café Central is located on Karolyi Street (named after the statesman) in a downtown university quarter. The Central, with its marble-top tables, ornate brass chandeliers, unpolished wood floors and white-aproned waiters, replicates a pre-World War I café.

Then there are the so-called romkocsma, or "ruined pubs," located in abandoned buildings scheduled to be torn down or renovated, which capture the avant-garde energy of the old coffeehouses better than the reproductions. Among the trendiest, Kuplung (Car Clutch) is housed in a space that was once an auto repair garage in the old Jewish quarter. The shabby-chic décor features discarded chairs and tables and old pinball machines on a cracked concrete floor; motley lanterns hang overhead. Patrons down beer and cheap wine diluted with mineral water to the raucous beat of heavy metal and rock 'n' roll.

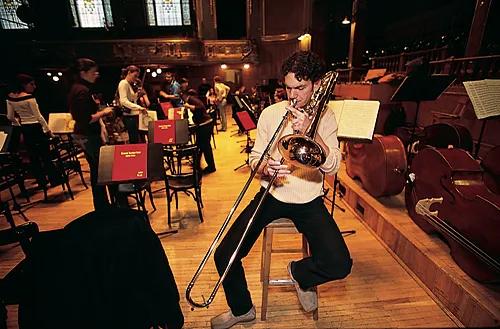

But it's classical music that really moves Hungarians. This nation of only ten million has assembled an awesome roll call of classical musicians—composers Franz Liszt and Bela Bartok, conductors Eugene Ormandy and Georg Solti, pianists Zoltan Kocsis and Andras Schiff. Hungarian string players, too, are world famous for their distinctive, velvety tone. "It is genetically impossible for a Hungarian musician to make an ugly violin sound," says Rico Saccani, the 53-year-old native of Tucson, Arizona, who conducts the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra (BPO).

At a three-hour rehearsal, Saccani greets the 70 musicians with a rousing Buon giorno! Swirling a tiny baton, he barks—"More staccato!" "Stronger crescendo!"—as he leads them through bombastic passages of Rossini’s 1823 opera, Semiramide, as well as works by Schumann, Grieg and Tchaikovsky. I ask Saccani how the orchestra has changed since Communist days. "In those times," he says, "because of generous state subsidies, many more operas and concerts were performed, and ticket prices were so low that attendance was huge." Since 1989, when government financing began to dry up, there have been fewer performances, and many seats are occupied by foreign tourists who can afford the higher ticket prices. The average monthly salary for a BPO musician is only about $700, before taxes.

The next day, one of those musicians, trombonist Robert Lugosi, 27, meets me at the nearby Liszt Academy, Hungary's premier music conservatory. As we wander the halls, muffled sounds of various instruments escape from the closed doors of small practice rooms. Lugosi shows me the school's 1,200-seat, Art Nouveau auditorium, reputed to possess the finest acoustics of any concert hall in Hungary. We pause in the place Lugosi describes as "for me, the most important in the building"—the front lobby stairwell where he met his future wife, Vera, who was a piano student at the time.

Torok, the guidebook author, speaks of Budapest as a layered city. "If you penetrate Budapest one way, it is a hectic, cosmopolitan place with wonderful museums, office buildings and shops," he says. "But approach it from a different axis and it becomes more humble and slower paced." On his advice, I board Bus 15 and spend 40 minutes crossing the city from south to north. The first half of the journey takes me past well-known landmarks: the massive Parliament building on Kossuth Square, named after the leader of the failed Hungarian independence revolt in 1848-49, and Erzsebet Park, the leafy preserve honoring the Hapsburg queen Elizabeth, admired for her sympathetic attitude toward Hungarian nationalists in the years before World War I.

But during the second half of my trip, the bus passes through far less prosperous neighborhoods. Beauty salons advertise long-outdated hairstyles; young men wielding wrenches tinker with motor scooters. Older women in dowdy clothes stroll by. Suit jackets sag on hangers behind open windows, airing out. Small family-run restaurants advertise home cooking and all-you-can-eat buffets.

"I still love those narrow, cozy streets—that is the city where I grew up," says Imre Kertesz, 76, Hungary's Nobel laureate in literature. We meet in the splendidly restored, marble-floored lobby of the Gresham Palace Hotel, a 1903 masterpiece of Art Nouveau architecture, where Budapest's most famous bridge, the Lanchid, straddles the Danube.

In Kertesz's childhood, more than 200,000 Jews lived in Budapest—one quarter of the city's inhabitants. By the end of Nazi occupation in 1945, more than half of them had been killed, many by Hungarian fascists. Kertesz himself survived both Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

After the war, he became a journalist, until he was fired for his reluctance to lionize the new Communist regime. "I could not take up a career as a novelist, because I would be considered unemployed and sent to a labor camp," he tells me. "Instead, I became a blue-collar laborer—and wrote at night." Still, he chose not to flee Hungary during the chaos of the 1956 uprising against the Communists. The Russian Army crushed the revolt, leaving an estimated 3,000 people dead, imprisoning thousands more and sending 200,000 into exile. "Yes, I could have left," says Kertesz, who was only 27 at the time and had yet to write his first novel. "But I felt I would never become a writer if I had to live in the West, where nobody spoke or read Hungarian."

His novels—the best known are Fatelessness (1975) and Kaddish for an Unborn Child (1990)—take up themes of pre-war Jewish life in Budapest and of the Holocaust. Although acclaimed internationally, his works were virtually ignored in Hungary until he received the Nobel Prize in 2002. The next year, more than 500,000 copies of his books sold in Hungary—or about 1 for every 20 countrymen. "But at the same time, there were many protest letters from Hungarians to the Nobel committee in Sweden," says Kertesz. "Most objections were about my being Jewish."

Kertesz divides his time between Berlin and Budapest. He remains controversial in Hungary, especially among conservatives, who regard an emphasis on Hungary's anti-Semitic past to be unpatriotic. I was surprised, therefore, when our interview was interrupted by former prime minister Viktor Orban, a staunch conservative, who greeted Kertesz warmly and professed admiration for his novels.

Hungary's bitterly polarized politics create the impression that the country is mired in a permanent election campaign. The acrimony is rooted in history. Many conservatives refuse to forgive former Communists and other leftists for their support of the Russians in 1956. Many leftists denounce the right for backing fascism during the 1930s and allying the country with Nazi Germany in World War II.

Orban is only 42. Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsany, who heads a coalition of socialists and centrists, is 45. "There is a very deep gap between the two sides," says Minister of Economy Janos Koka, himself only 33. "One reason is that democracy is very young and we aren't yet used to the new rules of the game." Still, he notes with pride, there has been no bloodshed in the 16 years since Hungary moved from a state-run to a free-market economy and from a Communist Party dictatorship to a multiparty democracy.

After making a fortune as a computer-software entrepreneur, Koka accepted an invitation to join the government and apply his business skills to the state bureaucracy. "Unlike the business world, it is very hard to turn a decision into action," he says. "You need a lot of enthusiasm to break through walls of government bureaucracy."

Hernadi, the oil company chairman, admires Koka’s brashness. "When I was as young as Koka, I also thought I could accomplish any task," he tells me. "But now I am 45, and trying to change the way government operates would be too much of a shock for me." Hernadi grew up 30 miles northwest of the capital, on the outskirts of Esztergom, a cathedral town where his father was a veterinarian. Recently, Hernadi bought a choice residential site on a hill facing Esztergom Cathedral. He then informed his wife, who is a Budapest native, that he wanted to retire to his hometown. "She told me, 'No way,'" Hernadi says. "That is how I realized that I had become a Budapester."

On my last day in the city, I attend a traditional Hungarian dinner, prepared by my youngest friend in Budapest, Judit Mako, 28, a press aide in the office of the prime minister. The meal, she told me, would not consist of the beef goulash with heavy, tomato-based sauce that most foreigners associate with Hungarian cooking. We meet to shop early on a Saturday morning at Central Market Hall, overlooking the Danube. The exquisite wrought-iron-and-glass structure, built in 1895, is almost as big as Budapest's main train station.

Mako suggests we first have breakfast at a small bar on the mezzanine. We order langos—flat, puffy bread with either garlic or a cheese-and-cream topping. Over strong coffee, we peer down at crowds of shoppers, and I am reminded of a touching vignette in Kertesz's most recent novel, Liquidation (2003), which also takes place at Central Market Hall. The main character, known only as B., waits his turn to buy vegetables. His former lover, Sarah, shopping nearby, sees him with his hands clasped behind his back. "She sneaked up behind him and suddenly slipped her hand into B.'s open palm," writes Kertesz. "Instead of turning around (as Sarah had intended), B. had folded the woman's hand tenderly, like an unexpected secret gift, in his warm, bare hand, and Sarah had felt a sudden thrill of passion from that grip...." The love affair resumes.

I follow Mako through the crowded aisles as she selects produce for her wicker shopping basket. At one stand she buys cauliflower, onions, garlic and potatoes; at another, carrots, cucumbers and tomatoes; at a third, kohlrabi, parsnips, turnips and cabbage. Last, but not least, she selects paprikas, the Hungarian peppers that are the essential seasonings of Hungarian cuisine. Mako buys fiery green paprikas and also a sweet, red, powdered variety.

Her three-room apartment, on the eastern outskirts of the city, has a view of the Buda Mountains beyond a green plain and thick forest. When I arrive toward sunset, I encounter a boisterous procession of neighbors—women dressed in traditional, brightly colored skirts and men wearing black suits and hats, singing and dancing as a violinist plays gypsy music. An elderly woman tells me they are celebrating the local grape harvest and offers me sweet, freshly made wine.

Mako takes two hours to prepare dinner. Most of the vegetables and a capon go into a soup. A young-hen stew, colored delicately red by the powdered paprika, is served with homemade noodles. The slivers of green paprika are so pungent that my eyes swell with tears. For dessert, Mako sets out a poppy-seed pudding with vanilla cream and raisins. Lingering over Hungarian cabernet sauvignon and pinot noir, the guests talk politics—the tightly contested recent elections in Germany and the expanding European Union, which Hungary joined in 2004.

One dinner guest, a young German lawyer married to a Budapester, says he has no intention of returning to Germany. Another, a French marketing executive who has spent two months as Mako's houseguest, has become so taken with the city she has decided to learn Hungarian and look for a job here. Mako counts herself lucky to have been born in an era of great opportunity—and to be in Budapest. "I wouldn't want to live anyplace else," she says.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.