Meet the Woman Fighting for the Survival of India’s Traditional Crafts Culture

Jaya Jaitly aims to protect India’s cultural heritage from the threat of globalized marketplaces

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/0b/8d0b7922-992d-415c-9bc8-5f759c800b71/sqj_1601_india_crafts_01-web-resize-v4.jpg)

Born in Shimla, in the foothills of the Himalaya, the daughter of an Indian civil servant in the British raj, Jaya Jaitly has lived many lives. She spent her childhood in Belgium, Burma and Japan, graduated from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, ran a camp for Sikh riot victims and became the high-profile president of Samata, a political party with socialist leanings.

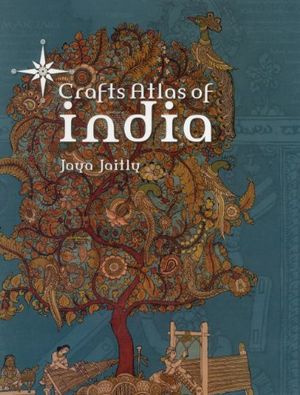

Running like a red thread through her life has also been a passion for India’s traditional crafts, helping them find viable markets and preserving their heritage. Her coffee-table book the Crafts Atlas of India is a love letter to the longstanding skills that make India’s crafts unique and colorful. She is also one of India’s foremost champions of the sari.

Speaking from her home in Delhi, she explains why the sari is the quintessential Indian garment, how the caste system helped preserve Indian crafts and why some artists are considered descendants of the lord of art.

You have been a leading politician in India, a trade union activist, prominently married and divorced. Tell us how you fell in love with crafts—and why their preservation matters.

I fell in love with them without knowing it when I was very young and living in Japan. My father was the Indian ambassador to Japan and loved beautiful things, like woven mats and shibori fabrics (an ancient Japanese method of tie-dye). It must have formed my aesthetic interests and love for handmade things.

In Kerala, where we come from, the lifestyle is very simple. There is not much furniture; we ate on banana leaves off the floor. I didn’t come from a highly decorated house; everyone wears simple white clothes in that region. So the simplicity and beauty of things have been ingrained into me instinctively.

After I got married, I moved to Kashmir, which is a craft-rich state. The craftspeople were very isolated, however, and not being noticed or given any advice. My mother was very active in social work. She was always helping the poor and needy, especially in hospitals. So I combined my interest in aesthetics with improving the life of the maker of that beautiful art.

The preservation of crafts matters because for many people, this is their livelihood. It is their respect and dignity, as well, so preserving the people and their lives means preserving their crafts and heritage. Much of India’s heritage would be lost if people lost their traditional skills. After we won our freedom from Great Britain, we needed to ground ourselves in our own histories, our own culture.

It was crucial for me as a socioeconomic exercise; you could call it a hidden political exercise. Early on, I didn’t think of my work as political, but now I see that preserving traditional arts and crafts answers many of the political narratives of India, as well.

Leafing though your gorgeous book, I was amazed by the variety from one end of the country to the other. How do regional influences inspire the creation of certain crafts? And are Indians themselves aware of this diversity?

Diversity in India applies to food, dress, dialect; what we make; ritual ceremonies and festivals. We are amazingly diverse. We are like the stray dog on the street. We have 101 influences in ourselves that most of us are not even conscious of.

Take Kashmir, where I lived for some time. In the 14th century, there were Hindu kings, but there were also Mogul influences that introduced the arts and crafts of Persia to us. There were carpetmakers, skilled painters, brass workers and wood-carvers. Carpet and shawl weaving led to beautiful embroidery, because someone had to stitch the salwar (loose trousers that are tight at the ankle). These things did not exist in Kashmir at that kind of high level before.

In the south, one of the big crafts, now more or less dying out, is metalwork. Brass diyas and kerelas are lit in temples. In the south, most of the crafts are related to temples, which are very important to the people in that region. There are little clay lamps for use in the temples made by local potters; palm leaf baskets holding flowers for puja made by local basket weavers; metal uruli platters that hold rice to feed the elephants. These southern crafts are made by the people who are descendants of Lord Vishvakarma, the lord of art.

India’s caste system is like a ball and chain for India’s progress but—another surprise—not for crafts. Why has the caste system helped preserve traditional artisanal crafts despite cultural pressures to modernize?

Since the 1990s, globalized marketplaces have opened up in India for goods from other countries. But cultural pressures to modernize are mostly directed toward the upper class. It was only the educated upper castes that had the option to move laterally and go from one kind of work to something else. The under castes did not have access to that kind of education or options. So this kept them rooted in their traditional identity and the traditional passing down of skills learned from parents, grandparents and local guilds. So they kept to their craft skills, partly because of forced immobility and the contained identity that was their only identity.

For instance, the kumhar is a potter; the bunker is a weaver. The surname Prajabati goes with those who belong to the Kumhar class of potters. The Muslim Ansaris and Kutris are the castes that are block printers and weavers. The name associates you with the caste, a bit like Smith or Carpenter

in English.

You cover everything from bronze and silver casting to textiles, ceramics, basketry, kites and stone carving. What craft is particularly dear to your heart—and why?

As a woman in India you automatically, like a magnet, go toward textiles. Most of us still wear Indian clothes, above all saris, and the variety of weaves in saris in different regions is breathtaking. It’s wonderful to be a woman in India who can choose to drape a lovely textile around her every day and go out to work. Then of course, the different traditional art forms, like wall paintings in people’s homes for specific ceremonies and festivals—that kind of art is now moving via canvas and paper onto fabric and even metal, wood and stone. There’s a lot of adaptation of art onto other surfaces.

You are a huge fan of the sari. Give us a glimpse inside your closet—and tell us why the sari is so important to Indian history and culture.

Saris are easier to buy than shoes [laughs] and much cheaper. We change the sari every day to wash and iron it. I don’t like wearing synthetic clothes. It doesn’t suit our climate. But if you’re wearing a pure cotton sari for the hot summer months, you do need to wash it after you’ve worn it. Or at least worn it twice. So, perforce, you need a fair number of saris. [Laughs] I have silk or warmer saris for winter, and then my summer saris. I would quite happily say that I have at least 200 saris. [Laughs] The beauty of a sari is that because you wear one and then put it away and wear another, they last a long time. I have saris that are as much as 50 years old, things that were passed down by my mother.

Many young women in urban areas think they should now wear skirts and long dresses and that it’s uncomfortable to wear a sari, which is a very sad thing. The kind of fashions now—five-inch heels, skinny jeans, plus a big, fat branded handbag—are much more uncomfortable than wearing a sari. But outside cultural influences have an effect on young girls in big cities, so in Bangalore, Delhi, or Mumbai, you find girls saying, “Oh, I don’t know how to wear a sari.” I counter that by saying a sari makes a woman feel natural and feminine. It displays our Indian culture through its weaving, block printing and embroidery. It also keeps a lot of handloom weavers in work.

Crafts Atlas of India

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.