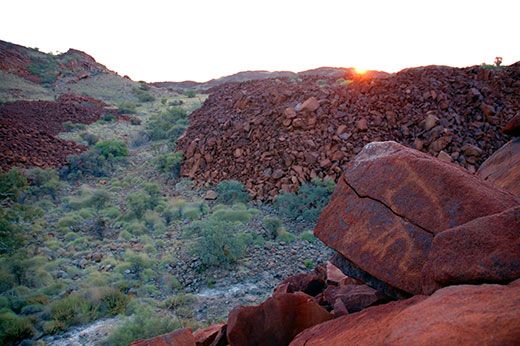

Dampier Rock Art Complex, Australia

On the northwestern coast of Australia, over 500,000 rock carvings face destruction by industrial development

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Dampier-Rock-Art-Complex-Australia-631.jpg)

The Dampier Islands weren't always islands. When people first occupied this part of western Australia some 30,000 years ago, they were the tops of volcanic mountains 60 miles inland. It must have been an impressive mountain range back then—offering tree-shaded areas and pools of water that probably drew Aborigine visitors from the surrounding plains.

No one knows when people first started scraping and carving designs into the black rocks here, but archaeologists estimate that some of the symbols were etched 20,000 years ago. As far as the scientists can tell, the site has been visited and ornamented ever since, even as sea levels rose and turned the mountains into a 42-island archipelago. Today 500,000 to one million petroglyphs can be seen here—depicting kangaroos, emus and hunters carrying boomerangs—constituting one of the greatest collections of rock art in the world.

But the petroglyphs sit atop a rich source of iron close to Dampier Port, which handles the second-most freight of any Australian port. By some accounts, industrial projects have already destroyed a quarter of the site, and archaeologists warn that continuing development could wipe out the rock art entirely.

The oldest petroglyphs are disembodied heads—reminiscent of modern smiley faces but with owl-like eyes. The meaning of these and other older engravings depicting geometric patterns remains a mystery. But the slightly younger petroglyphs, depicting land animals from about 10,000 years ago, lend themselves to easier speculation. As with most art created by ancient hunting cultures, many of the featured species tend to be delicious. (You might try kangaroo meat if you get a chance—it's very lean and sweet.) Some of the more haunting petroglyphs show Tasmanian tigers, which went extinct there more than 3,000 years ago. When the sea levels stopped rising, about 6,000 years ago, the petroglyphs began to reflect the new environment: crabs, fish and dugongs (a cousin of the manatee).

Interspersed among the petroglyphs are the remains of campsites, quarries and piles of discarded shells from 4,000-year-old feasts. As mountains and then as islands, this area was clearly used for ceremonial purposes, and modern Aborigines still sing songs and tell stories about the Dampier images.

Archaeologists started documenting the petroglyphs in the 1960s and by the 1970s were recommending limits on nearby industrial development. Some rock art areas gained protection under the Aboriginal Heritage Act in the 1980s, but it wasn't until 2007 that the entire site was added to Australia's National Heritage List of "natural and cultural places of outstanding heritage value to the nation." That listing and various other protections now preclude development on about 100 square miles of the archipelago and mainland, or about 99 percent of the remaining archaeological site. Meanwhile, tourists are still welcome to explore the rock art freely, and talks are in progress to build a visitor center.

That may sound like success, but the iron ore mines, fertilizer plants, liquid natural gas treatment facilities and other industries on the remaining 1 percent of the site can still wreak a lot of havoc. "The greatest impacts are not direct but indirect," says Sylvia Hallam, an archaeologist at the University of Western Australia who has studied the complex extensively. Acid rain from the gas facilities could etch away the rock art; roads, pipelines and quarries have damaged sites such as shell piles that help archaeologists interpret the petroglyphs; and—worst-case scenario—fertilizer plants can explode. A company building a new gas-processing plant recently received a permit to move rocks that host 941 petroglyphs. Relocating the ancient works of art prevents them from being bulldozed, but it also removes them from their archaeological context.

"The art and archaeology of the Dampier Archipelago potentially enable us to look at the characteristics of our own species as it spread for the first time into a new continent," says Hallam, and to study how people adapted to new landscapes as sea levels rose. But there's also meaning in the sheer artistry of the place. The petroglyphs, Hallam adds, allow us "to appreciate our capacity for symbolic activity—ritual, drama, myth, dance, art—as part of what it means to be human."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)