One Man’s Epic Rail Journey to the Darjeeling Himalaya

A grandson retraces adventurer Francis K.I. Baird’s mysterious trek to a remote village near the India-Tibet border

The weather-beaten door swung open with little resistance, and I followed Rinzing Chewang into the unlit bungalow. “Watch out!” he said in accented English, and I dodged a gaping hole in the floor just in time. We crossed a high-ceilinged parlor, where a framed poster of the Buddha, draped in a white silk khata, gazed at us from a soot-tinged mantel.

At the end of a dim hallway, Rinzing pushed open another door and stood back. “This is the bedroom,” he announced, as if he were showing me to my quarters. A pair of twin beds, the room’s only furnishings, stood naked, mattresses uncovered, pushed up against a dull yellow clapboard wall. Gray light seeped in through a grimy window. Walker Evans’s Alabama sharecroppers might have lived here.

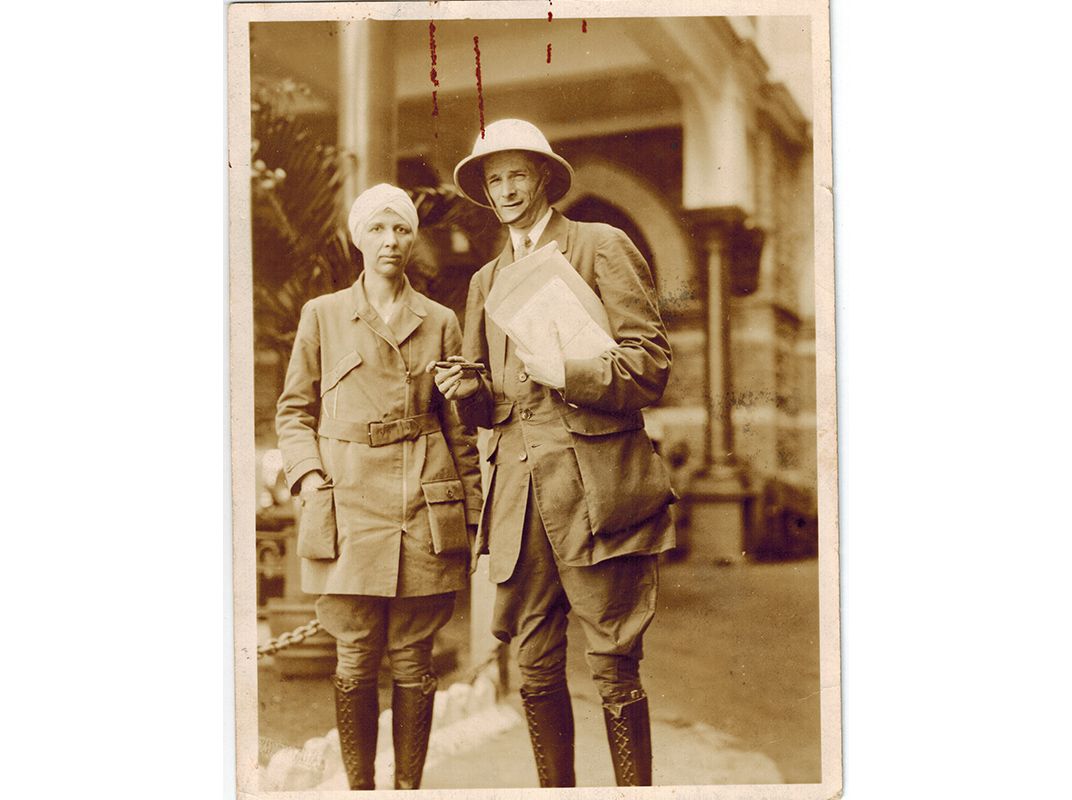

Who actually had stayed here, I’d recently discovered, was a tall Scotsman of rugged good looks and incurable wanderlust. Francis K. I. Baird. My maternal grandfather. In 1931, he and fellow adventurer Jill Cossley-Batt journeyed to this remote Himalayan village, called Lachen, in North Sikkim, near the border of Tibet. Somewhere in these borderlands, the couple claimed to have discovered a “lost tribe” of cave dwellers living high up a mountain wall. The clan folk were unsullied by Western avarice, the adventurers proclaimed, and they lived well past the age of 100.

At the time, Lachen was an isolated settlement composed almost entirely of self-sufficient indigenous farmers and herders with strong familial ties to Tibet. Hanging on the lip of a ridge amid thundering brooks and plunging, fir-covered slopes, the village still retains much of its bucolic charm. Along the rutted dirt road that serves as its main thoroughfare, Baird and Batt found shelter in this so-called dak bungalow. Resembling a rough-hewn English cottage, the structure was one of dozens, if not hundreds, of such peak-roofed bungalows built in the time of the raj to billet officers along military roads and postal routes spanning the vast reaches of British India. Back in Baird’s day, the bungalow would have been more comfortably furnished. Now it was all but abandoned behind a locked gate, evidently slated for demolition.

My mother was not yet five when she waved goodbye to her father as he boarded an ocean liner on the Hudson River in 1930, bound for India. He promised to return rich and famous, flush with tales of wonderment to recount to his adoring daughter, Flora. It was a promise he did not keep.

Ten years passed before my mother next saw him, in a chance encounter on the New York waterfront. The meeting was stiff and perfunctory, over in a matter of minutes. She never laid eyes on him again. Until the end, her father remained a man of unanswered questions, a purveyor of mystery and source of lifelong bereavement. She went to her grave without knowing what had become of him. She knew not where he died, when he died, or even if he’d died.

“Your grandfather would have slept in this room,” said Rinzing, snapping me back to the moment. I pulled back the window’s thin curtain and looked out on a stack of rain-soaked firewood and, beyond it, mountain slopes rising sharply and vanishing in a swirl of mist. This would have been the same view that Baird beheld each morning during his stay here so long ago.

In the dozen years since my mother’s death, I have initiated a quest of my own: to find out more about this man I never met, and to uncover the hidden role he has played in shaping my life and strivings. I have unearthed scores of documents—occasional letters he sent home, news clippings, photographs, even a film clip shot by the couple during their journey into the Himalaya. I found an obituary so deeply buried inside the archives of the New York Times that an ordinary search through the paper’s Web portal does not reveal it. (He died in 1964.)

Of particular interest is a file compiled by the British India Office, whose officers were deeply suspicious of Baird and Batt, fearing they would provoke an incident if they entered Tibet. The office even assigned an agent to tail them. That was how I came to find out they’d stayed here in Lachen’s dak bungalow. And now, here I was, standing for the first time in my life in a room where I knew my grandfather had slept.

“Maybe we go now?” Rinzing suggested. A robust man of medium height and irrepressible good humor, Rinzing, 49, is Lachen’s postmaster. Like so many people I’d met since arriving in India, he enthusiastically offered to help as soon as I explained the nature of my mission. His grandfather, it turned out, was the village headman at the time Baird came to town. “They would have known each other,” he said.

I’d begun the journey to retrace my grandfather’s footsteps in Kolkata (previously called Calcutta) ten days earlier. The city was in the midst of preparing for the massive, weeklong Durga Puja festival to celebrate the ten-armed Hindu goddess Durga. Workers were stringing lights along the boulevards and raising bamboo-framed pavilions that would house enormous, handcrafted like-

nesses of the goddess mother and her pantheon of lesser deities.

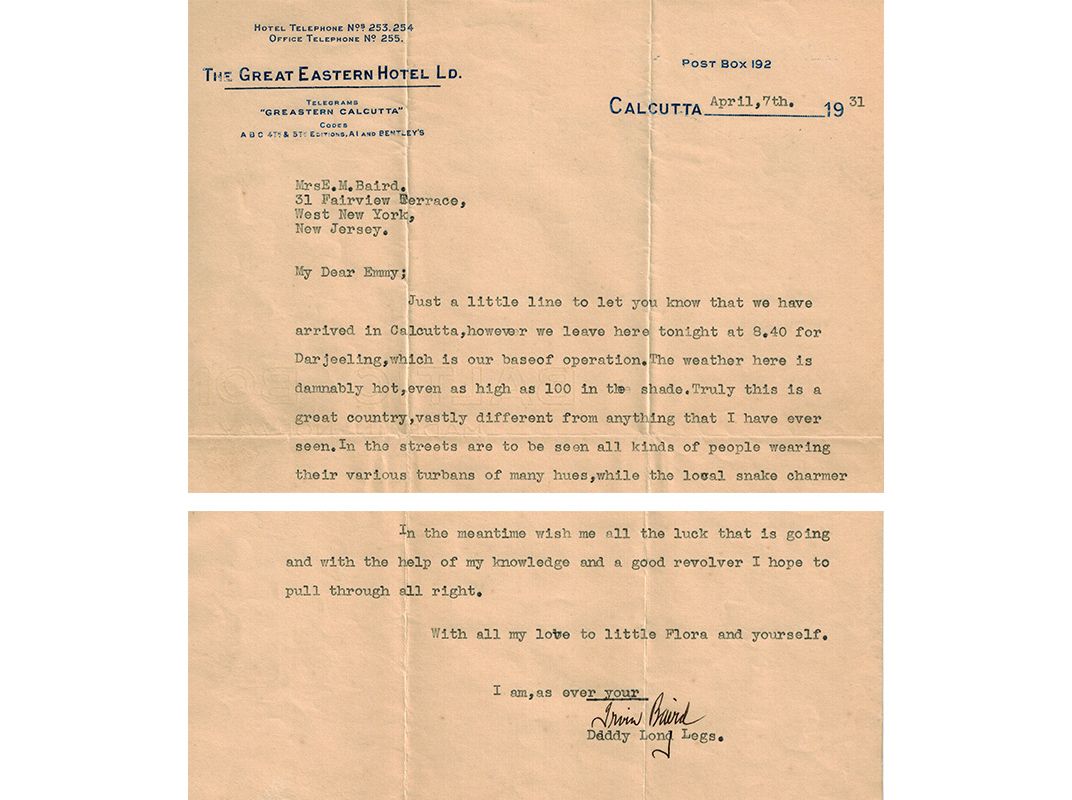

I knew Baird had started his quest here as well. I was in possession of a letter he’d sent home from Calcutta in the spring of 1931. He noted the “damnably hot” weather, as well as the startling spectacle of raw, unvarnished humanity on display on the city streets: pilgrims, hustlers, snake charmers, “Untouchables” sleeping openly on the pavement. The letter was written on stationery from the legendary Great Eastern Hotel.

Known back then as the Jewel of the East for its unrivaled opulence, the Great Eastern has hosted such luminaries as Mark Twain, Rudyard Kipling and a young Elizabeth II. It’s been in the throes of renovation for the past five years under ownership of the Delhi-based Lalit hotel group, and sheet-metal blinds obscured much of the hotel’s stately, block-long facade of columns and crenelated parapets. Still, it was a thrilling sight to behold as I stepped from my cab into the liquid heat of midday.

A turbaned sentry smiled through a regal mustache as I passed through a metal detector and entered the hotel’s gleaming, ultramodern lobby. Chrome, marble, fountains. A rush of attendants—men in dark suits, women in flaming yellow saris—bowed to greet me, their palms pressed together in a gesture of disarming humility.

To get a better feel of what the old hotel was like, I asked concierge Arpan Bhattacharya to take me around the corner to Old Court House Street and the original entrance, currently under renovation. Amid blaring horns and the roar of exhaust-belching buses, we sidestepped beggars and ducked under a low scaffold. “This way led to the rooms,” said Arpan and gestured up a stairway. “And this other side led to Maxim’s.” I followed him up the steps. We entered a spacious, vaulted room where masons with trowels and buckets of cement were restoring the old club. Maxim’s had been one of the most glamorous nightspots in all of British India. “Not everyone could come here,” Arpan said. “Only high-class people and royalty.” As workers restored the past in a din of whining machinery, I had the strange sensation of catching a glimpse of Grandfather at his most debonair. He was bounding up these steps, Jill on his arm in slinky dress and bobbed, flapper hair, keen for a last night of music, drink and merriment before the next day’s train north toward the Himalaya.

It would have been easier for me to hop a quick 45-minute flight to Siliguri’s airport, Bagdogra. From there, I could have hired a car for the onward journey to Darjeeling. But in the early 1930s, the only viable way into the northern mountains was by rail, particularly since Baird and Batt were hauling dozens of crates packed with gear and provisions. Rail was the best way to re-create their journey. I would take the overnight train to Siliguri and from there catch the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, the celebrated “Darjeeling Express.” It was the same train they’d have taken on their way into the mountains.

My own luggage was modest by comparison: a suitcase and two smaller bags. Friends nonetheless had warned me to keep a close eye on my belongings. Sleeper cars are notorious sinkholes where things go missing, particularly in the open compartments and aisle berths of second class. Having booked at the last minute, second class was the best I could do. As I reached my assigned upper berth on the aisle, I wondered how I would manage to safeguard my stuff.

“Put it under here,” came a lilting voice from across the aisle. A woman in her mid-50s was pointing beneath her bunk, which was perpendicular to the corridor and offered much better protection. She wore a long, embroidered dress and matching pink head scarf. Her forehead was adorned with a bright red bindi, and she wore a gold stud in her nose. Despite her Bengali dress, there was something in her aquiline features and British accent that suggested she was from elsewhere. “I’m A.I.,” she said with a brilliant white smile. “Anglo-Indian.” Born to a British father and an Indian mother, Helen Rozario was an English teacher at a private boarding school in Siliguri. She was on her way back there after seven months of cancer treatments in Jharkhand.

A trim teenager in black T-shirt and coiffed pompadour came aboard and stowed a guitar on the upper bunk opposite Helen. “My name is Shayan,” he said, offering a firm handshake. “But my friends call me Sam.” Though music was his passion, he was studying to be a mining engineer in Odisha, a restive state rife with Maoist insurgents. “I plan to be a manager for Coal India.” He’d wanted to stay put on campus and study for upcoming exams, but his family had other plans. They insisted he return home for the holidays, to Assam in India’s northeast. “My mother is forcing me,” he said with a rueful smile.

Soon we were beset by a nonstop parade of freelance vendors pushing down the aisle, hawking spicy peanuts, comic books and plastic figurines of the Durga. Helen bought me hot chai, served in a paper cup. I wondered if it all wasn’t a bit much for a grown woman traveling on her own: the dingy bunks, the relentless assault of peddlers, the heavy scent of urine wafting through the car. “The train’s all right,” she said cheerfully. She said she’d never been on an airplane. “One day I’d like to try it.”

I passed a night of fitful sleep, curled up on the narrow bunk, the lumpy backpack I’d stuffed with camera and valuables for a pillow. It was barely dawn when Helen arose and drew open the window shade. Outside, tin-roofed shacks slid past amid expansive fields of rice, tea and pineapple. “Get your things ready,” said Helen, rummaging around beneath her berth. “Our station’s coming up.”

His destination was still far off, but Sam joined us on the platform to bid farewell. I couldn’t have asked for a merrier pair of travel companions. As a pale yellow sun rose over the rail yard, I scribbled down Helen’s phone number. “Call me someday,” she said and vanished in the crowd.

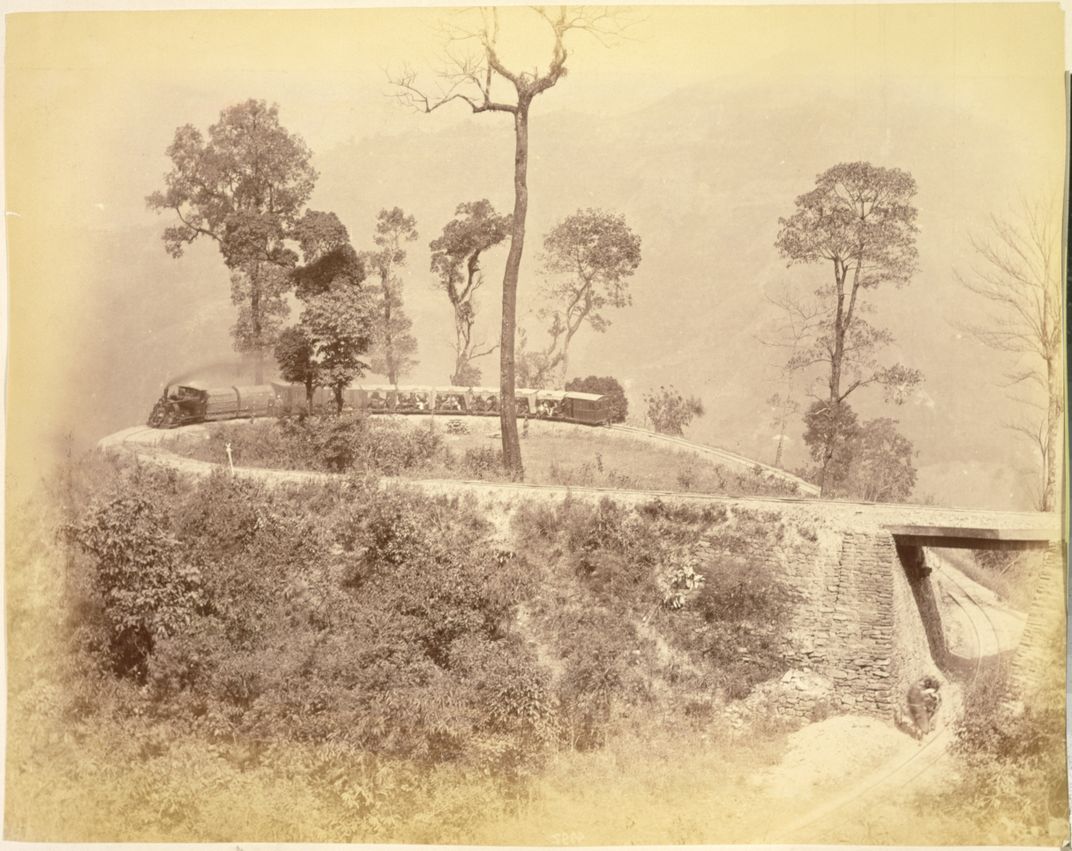

The train to Darjeeling has a platform of its own at Siliguri’s old railway station, a short car ride from the main terminal. That’s because it still runs on the same narrow-gauge track designed by British engineers 130 years ago to haul colonial administrators, troops and supplies up 7,000 vertical feet to the burgeoning tea estates of Darjeeling. The advent of the railway in 1881 put Darjeeling on the map. It soon became one of the most prominent hill stations in British India—the summer command center and playground for viceroys, functionaries and families seeking to escape the heat and multitudes of Calcutta.

The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway also served as a conduit for a growing legion of adventurers heading into one of the world’s most untamed, majestic and formidable regions. George Mallory figured among the succession of early 20th-century mountaineers who journeyed aboard the train on the way to Everest via Sikkim and Tibet. In 1931, the DHR bore Baird and Batt with all their supplies to Darjeeling, the operational base for their enterprise, which they christened the British-American Himalayan Expedition with no small measure of grandiosity.

Goats rummaged languidly in the midmorning sun, as I waited for the train to arrive. Finally, nearly an hour behind schedule, a blue diesel locomotive backed into the station, pushing three passenger cars. It was immediately apparent that the railway’s narrow-gauge specs had miniaturized its moving stock as well: The engine and the cars were each about half the size of a typical train. Because of its diminutive size—and perhaps also because some of its locomotives are steam engines that bear a strong likeness to Thomas the Tank Engine—the rail line is popularly called the Toy Train.

The tracks ran right alongside the road, crossing it back and forth as we climbed through tea plantations and banana groves, slowly gaining altitude. I’d anticipated a crush of railroad enthusiasts would fill the historic train. The rail line was granted UNESCO World Heritage status in 1999, and tourists flock here from all over the world to experience an authentic, old-time train ride in a spectacular setting. But I was nearly the only passenger aboard. Landslides in recent years have cut off the middle section of the railway to Darjeeling. Because there is no longer direct service for the entire route, most travelers drive to Darjeeling to pick up a train there. They take a leisurely round-trip excursion along a 19-mile stretch of the track to Kurseong, powered by one of the railway’s original steam engines. But for my purposes—I wanted to retrace exactly the route Baird and Batt would have followed—I devised a way to bite off the trip in three chunks: by train, then car, then train again.

And there was something else. A short black-and-white film shot by the couple had come into my possession a few years back. I’d had the film restored and was carrying a digital copy of it on a USB drive. The film opens with a locomotive trailing clouds of steam as it hauls a string of cars around a distinctive loop set amid alpine forests. I suspected that train was the Darjeeling Express. If I followed the old route, I reasoned, I might even be able to recognize the exact spot where the novice filmmakers had positioned their camera.

So I arranged for a driver to be waiting when I disembarked at the gingerbread-style Victorian station in Rangtong, 16 miles up the line, the terminus for the first stretch of track from Siliguri. From there, we’d bypass the landslides and arrive in the mountain town of Kurseong in time for me to connect with another heritage train that ran the final 19-mile leg to Darjeeling. My driver, Binod Gupta, held open my door as I piled in. “Hurry, please, sir,” he said. “We’re running late.”

Gupta was a former soldier and mountaineer with the build of a linebacker and the sad eyes of a basset hound. His driving skills were superb. He rarely shifted out of second gear, as we snaked back and forth through a death-defying gauntlet of single-lane switchbacks and plunging drop-offs. A stunning panorama of lofty peaks and deep green valleys unfolded out the window as Gupta gunned the car up a washed-out path, children on their way home from school shouting and waving at us. “Everyone is more relaxed up here,” he said. “People enjoy life more here than down on the plains.”

There were a good many more passengers aboard the train out of Kurseong. A half dozen women from France, all M.B.A. students spending a semester in New Delhi. A group of operatives from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, on vacation from the state of Uttar Pradesh. I wondered what had attracted the BJP activists to this particular corner of India. “It’s the mountains and the forest,” said Surendra Pratap Singh, a bewhiskered farmer and former legislator in the state assembly. “We love the nature.” The friends vacationed together whenever they could, said Singh, prompting vigorous nods from his associates. “We want to see all of India,” he said. “Life is very small.” It took me a moment, but I got his point. Life indeed is very short.

We entered the city of Ghum, the train chugging along the main road, horn blaring nonstop. Brightly painted concrete buildings of three and four stories crowded the track, rising precariously just overhead. Kids took turns jumping on and off the slow-moving train. We passed beneath a

narrow bridge and started climbing along a tight, looping stretch of track.

The Batasia Loop is one of three such engineering marvels on the railway between Siliguri and Darjeeling. This particular loop allowed our train to gain nearly a hundred feet in elevation as it circled tightly and crossed the same bridge we’d just gone under. The lay of the land was unmistakable. I could even make out the elevated bluff from which Baird and Batt had filmed the circling train so many years ago.

I passed through the gates of the Windamere Hotel as darkness was falling. And just like that, I felt as if I’d been transported 80 years back in time: Uniformed, white-gloved waiters tended to couples huddled at candlelit tables listening to the strains of a thirties jazz crooner. The hallways were covered with fading black-and-white photographs: black-tie dinner parties, women in embroidered silk blouses and heavy jewelry, braids of thick black hair coiled high atop their heads. There was a teak-paneled library named for journalist Lowell Thomas, a sitting room commemorating Austrian explorer Heinrich Harrer, author of Seven Years in Tibet, and a parlor bearing the name of Alexandra David-Néel, the Belgian-born acolyte of high Buddhist lamas, who clawed her way to the forbidden city of Lhasa in 1924, disguised as a beggar.

My own cottage bore the simple name of Mary-La, which prompted little thought as I unpacked and caught sight of a notice left on the bed. “Please do not open your windows during your stay,” it warned. “Monkeys will be sure to enter.” The primates had exhibited unusual boldness in recent months, according to the advisory, staging raids on the hotel grounds from their sanctuary at the Mahakal Temple just up the hill. In truth, the only monkeys I saw during my stay in Darjeeling were at the shrine itself, loping along the compound walls, snatching handouts from worshippers.

On the advice of Windamere’s obliging director, Elizabeth Clarke, I asked two women with deep roots in the community to join me for tea the next afternoon. Maya Primlani operated Oxford Books, the city’s premier bookstore, on the nearby square. Noreen Dunne was a longtime resident. Something might occur to them, Elizabeth thought, if they watched the short movie shot by Baird and Batt in 1931.

In a letter home from London, where the couple stopped on their way to India to take on provisions, my grandfather reported that he’d procured 10,000 feet of film, among many other corporate donations. What became of all that footage remains a mystery; I’ve managed to find only an 11-minute clip. In just two days in town, I’d already identified many of the locations shown: Darjeeling’s bustling old market, where they’d recorded tribal women selling vegetables; distant, snowcapped mountains, dominated by Kanchendjunga, the world’s third highest peak. But I hadn’t identified the monastery where they’d filmed an elaborately costumed lama dance, nor had I made much sense of a scene showing multitudes in homespun mountain clothing, gorging on flatbread and dumplings.

Over tea and scones, I ran the film clip for Maya and Noreen. The lama dance began. “That’s the Ghum monastery!” said Noreen, leaning in for a closer look. I’d passed through Ghum on the train, but I hadn’t gone back there to explore. I made a note to do so. Then came the footage of the feasting crowds. It was a Tibetan New Year celebration, Maya and Noreen agreed. The camera panned across a group of elegantly turned-out ladies sitting before a low table stacked with china and bowls of fruit. One face stood out: that of a lovely young woman, who flashed a smile at the camera as she raised a teacup to her lips. “Look!” Maya gasped. “It’s Mary Tenduf La!” She steered me to a portrait of the same woman in the hallway. The daughter of Sonam Wangfel Laden La, special emissary to the 13th Dalai Lama and onetime police chief in Lhasa, Mary Tenduf La married into another prominent family with roots in Sikkim and Tibet just months before my grandfather’s arrival. Mary Tenduf La came to be known as the grande dame of Darjeeling society. Her friends called her Mary-La. The name of my cozy room overlooking the city.

Baird and Batt obviously did not stay at the Windamere; it wasn’t yet a hotel. But they must have known the Laden La family, and it’s likely they knew Mary. There was another detail I picked up from Maya and Noreen: the Laden Las maintained close ties with the monastery in Ghum called Yiga Choeling. That might explain how Baird and Batt gained access to film the lama dance that day. Some pieces of the puzzle were beginning to fit together.

The monastery is perched on a ridge at the end of a narrow road etched into a plunging mountain slope, a short drive from the Ghum railway station. It’s a modest structure: three whitewashed stories topped with a swaybacked roof and gold ornamental spire. A set of 11 brass prayer wheels flanked either side of the four-column entrance. It looked a lot like the monastery where my grandfather had filmed the lama dance. But I wasn’t sure.

Chief lama Sonam Gyatso greeted me in the courtyard, wearing an orange fleece jacket over his maroon robes. He was a charming man in his early 40s, tall and handsome, an epicanthic fold to his eyes and the high cheekbones that hinted at origins on the Tibetan plateau. Indeed, he’d left the Amdo region of Sichuan in China in 1995. For the past several years, he’s been responsible for running the monastery, the oldest in the Darjeeling region, belonging to the Gelugpa Yellow Hat sect of Tibetan Buddhism.

He invited me to a cup of tea in his spartan living quarters. Once more, I played the film clip of the lama dance. A pair of monks are seen blowing horns as a fantastical procession of dancers emerges from the doorway. They’re dressed in elaborate costumes and outsize masks representing horned creatures with bulging eyes, long snouts, menacing smiles. They hop and spin around the monastery courtyard, culminating with four leaping dancers in skeleton outfits and masks of smiling skulls.

“This was filmed here,” lama Gyatso said without hesitation. “Look at this.” He thumbed through photos on his smartphone and produced a black-and-white image of robed monks in front of the monastery’s entrance. It would have been taken around the same time as the film clip, he said. “You see, the columns are exactly the same.” What was more, Gyatso said, the same skeleton costumes were in a storage room in the back of the monastery. He called an assistant to find them.

Whatever doubts I may still have harbored about having found the right monastery vanished once I held the home-stitched garments in my hands. To my surprise, the outfits in real life were red and white, not black and white. Yet the design of each hand-sewn piece of rough cotton was exactly the same as in the film. I felt a chill run down my spine.

I considered the strange chain of events, spanning three generations and 85 years, that had led me here. I’d flown across 11 time zones, journeyed by rail across the sweltering plains of Bengal and up through the lush tea estates of Darjeeling and into the mountains beyond, searching for Baird and some understanding of his legacy. I’d wondered if my grandfather wasn’t a fabulist, on top of everything else. I asked Gyatso if he thought my grandfather’s claim of discovering a “lost tribe” in the borderlands farther north had any merit. “It’s possible,” he said, nodding solemnly. Back then, he continued, there were any number of self-sustaining communities that had little contact with the outside world. “You would have had to walk a long way through the mountains.”

The lama led me out to my car. The morning fog was lifting, and I could see all the way down the mountain to the valley floor far below. It was a landscape that seemed to demand humility and reverence from all its beholders. Is that what my grandfather had seen here, too? I hoped so. “I am very happy that you have come back after two generations,” Gyatso said, throwing his arm around me. “See you again.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1601_India_Contrib_01.JPG)