Day 1: Seeing Kenya from the Sky

Despite many travel delays, Smithsonian Secretary Clough arrives in Kenya ready to study the African wildlife at the Mpala Ranch

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Nairobi-Kenya-631.jpg)

June 13, Nairobi, Kenya. Weather: Sunny, warm and humid. Mpala Ranch (elev. 6000 feet): Sunny, warm, cool breezes.

The redoubtable Francine Berkowitz, director of international relations for the Smithsonian informs me that the Institution and its people are involved in activities in 88 countries, ranging from large permanent operations like the Panama to remote sites visited only occasionally by researchers and scientists collecting data. These international operations are critical to the diverse and varied work of the Smithsonian and that that is what brings me to Kenya.

I am here to visit the Africa that are at risk as the human population encroaches into what was once natural habitat.

Smithsonian scientists from the STRI, and the Secretary Robert Adams signed a cooperative agreement with the center. A number of SI researchers are at Mpala during my visit, including Biff Bermingham, STRI's director; soil scientist Ben Turner, Senior Scientist Emeritus Ira Rubinoff and Dave Wildt, head of the Center for Species Survival at the Zoo.

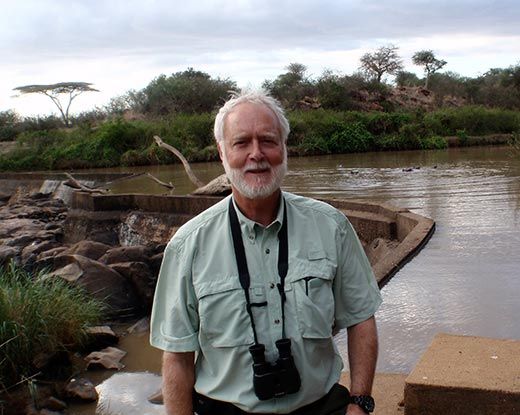

At places like Mpala, there is a chance to preserve a part of the natural world that is fast disappearing. Mpala is home to a stunning array of African wildlife, as diverse as that found at larger preserves like Serengeti . At the same time, Mpala is situated among several working ranches and the Mpala Ranch itself has a substantial cattle herd. African people, including the fabled Maasai , occupy community lands and move their cattle and goats from one place to another to seek better grazing for their animals. Mpala offers the opportunity to understand how people and wild animals might coexist so that both can succeed. My job as Secretary is to better understand the Smithsonian’s role in this important work and how it may evolve in the future.

Kenya is a country blessed by geographical diversity, ranging from a windblown coastline and the high elevations of Mount Kenya to desert in the north. The Mpala Ranch is located roughly in the middle of Kenya, about 20 miles north of the equator. It lies on the flanks of Mount Kenya, an extinct volcano that looms to the east of the Ranch. Rainfall averages about 20 inches per year, but it is not consistent and currently, Mpala is in the throes of a drought.

Mpala Ranch owes its existence to the vision of two brothers, Sam and George Small who fell in love with this land. Sam purchased the land in 1952 and left it to George when he died in 1969. George believed the land should be preserved and used as a center for research into the preservation of the flora and fauna. He also understood the obligation of landowners to the people of the region and provided for a state-of-the-art health clinic and schools for the children. In 1989, George created the Mpala Wildlife Foundation. Mpala is funded through the foundation, established and administered by the Mpala Research Trust, in collaboration with Princeton University, the Smithsonian, the Kenya Wildlife Service and the National Museums of Kenya.

My wife, Anne, and I arrive in Nairobi early on the morning of the June 12 and are met by our Smithsonian colleague, Scott Miller, the Deputy Under Secretary for Science. Our journey from Washington, D.C., was to have taken about 24 hours, but due to weather delays for the first leg of our flight, we missed our connection from London to Nairobi and had to wait 12 hours for the next flight. We arrive in Nairobi at around 6 a.m. after 36 hours of travel, a bit wanting for sleep, but excited about being here. In Nairobi we transfer to a local airport for the short flight to Mpala. On the drive to the airport, we watch Nairobi waking up. Throngs of people are on the move. The streets are full of cars, trucks, buses and bicycles. There are thousands of pedestrians, including boys and girls in school uniforms. The school buses illustrate the religious diversity of Kenya with some representing Christian schools and others, Muslim schools.

Our Mpala flight initially takes us over land that is as green as Ireland, indicating high levels of rainfall and rich soil. As we continue north and come within sight of Mount Kenya and its peak, the land becomes brown and reflects a transition to a country with low precipitation. We learn later that much of the land also has been overgrazed by goats and cattle, as well as wild animals, causing serious problems in some areas near Mpala. Our pilot makes a low run over the dirt airstrip at Mpala Ranch to frighten off any animals that might be on the runway before we land smoothly in a cloud of dust. We are greeted by Margaret Kinnaird, executive director of the Research Center and others of the SI team who arrived earlier.

We drive in an old-school Land Rover over dirt roads to the Mpala Ranch headquarters. The trip is jolting at times when ruts and rocks are encountered. The Ranch is composed of a series of low stone and stucco buildings with sloped roofs. Each building, designed for utility, has its own character, and the ranch has a charm all its own in the middle of the large dry savannah. Our room is spacious with clay tile floors a large bed with a wrap-around mosquito net to keep the pesky creatures at bay.

We take lunch at the Research Center, a nearby complex of buildings with living quarters for students and visiting faculty, laboratories, computer rooms and an open-air dining hall. We are pleased to learn that the Smithsonian Women’s Committee provided funding for several of the buildings at the Research Center. After lunch we are treated to a series of talks that introduce us to the research done at Mpala.

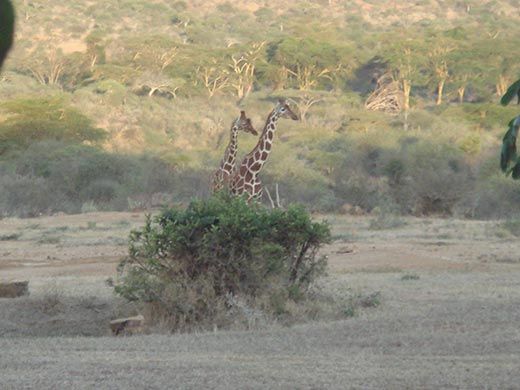

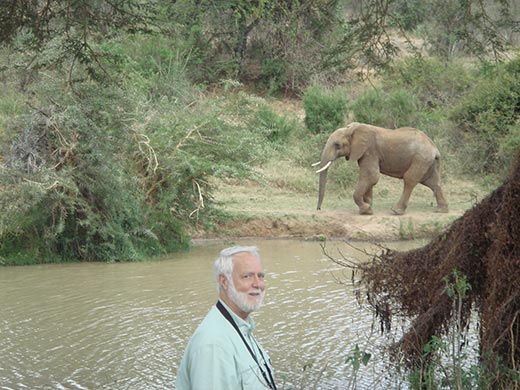

At about 4 p.m. we break up and head out in Land Rovers on a “wildlife drive” to explore. Early on, we spot three cheetahs through binoculars. As we drive slowly along, the spotters on top of the vehicle thump the roof as a signal to spot if an animal is sighted. In some cases, you don’t really have to look very hard—elephants, gazelles and impala amble across the road at their pleasure. Others, like the beautifully colored bushbucks, shy from human contact. By the end of the wildlife drive, the list of species we have seen includes bushbuck, dik-dik, warthog, impala, giraffe , mongoose, scimitar-horned oryx , elephant, hippo , Cape buffalo, kudu , cheetah, hyenaand Grevy’s zebra (an elegant zebra with small black and white stripes). Remarkable!

We conclude the day with a wonderful al fresco dinner perched on a ridge overlooking a wide canyon. The air is sweet and the scenery distinctly Kenyan. With sunset, the temperature drops quickly and we crowd around a roaring fire. Finally, jet lag kicks in around nine and we call it an evening after an eventful day that we will long remember.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)