Day 3: The Excitement of Astronomy

A daytime tour of the Magellan facility and its surrounding hillside is topped off by a perfect evening of stargazing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Smithsonian-Secretary-G-Wayne-Clough-Magellan-telescopes-388.jpg)

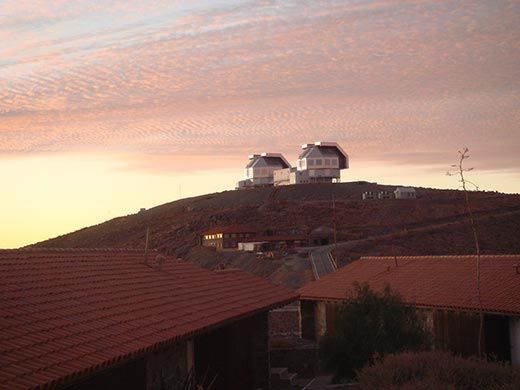

Day Three, May 26. Las Campanas. Morning, weather brisk and breezy. Light clouds.

Day begins with trip to the twin Magellan telescopes. The mirror for each telescope is 6.5 meters in diameter and is housed in a framing system that is a mechanical marvel. The foundation for each of them was created by digging a hole 30 feet in diameter and 30 feet deep. This provides a base that will avoid vibrations and firmly support the framing system. The frame itself contains mechanisms that move the mirror smoothly in spite of its heavy weight. There are mechanisms beneath the mirror that allow its shape to be adjusted to account for the effects of its own weight on the mirror itself. Lessons learned from the Magellan telescopes will be put to good use with the 8-meter Giant Magellan Telescope mirrors.

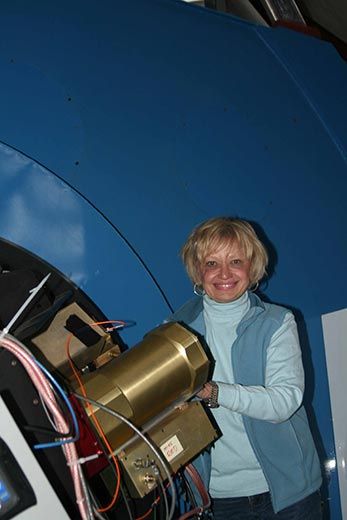

Toward the end of our visit, Andrea Dupree, a senior astrophysicist at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (and a very helpful contributing editor on this journal entry!), took me up the ladder on the side of the telescope so I could see her favorite instrument on the Magellan telescope—a spectrograph (named MIKE) that breaks starlight up into colors that reveal physical conditions in the star itself and its surroundings. Andrea uses the information to detect winds and material lost from the youngest and oldest objects in our galaxy—including stars in the old cluster Omega Centauri. This helps us to understand the life history of the stars themselves and provides information about stellar evolution. Andrea's enthusiasm is evident—she obviously loves her life work!

After our tour of the Magellan facility, we go off schedule for a few hours for lunch and time to explore the site on our own. Later in the day we will review the GMT partnership and the status of the project, followed by an opportunity at night for us to actually view the stars using the Magellan telescope.

For my time off, I decide to explore the trails around the site to look for wildlife and take in the dramatic scenery. In the course of my walk, I see a beautiful hawk soaring in the valley below. The hawk has a strong resemblance to the Red-Tailed Hawk seen in the southeastern United States, but it has a white breast with a white tail. Walking around a bend in the road, I come upon three wild burros grazing on the hillside. They seem well fed, and my presence does not spook them. Later I learn they may have become acclimated to humans because they get a few handouts from the cooks at Las Campanas.

My exploration turns up other small mammals and birds that live among the rocks in the hills and valleys. Vegetation, what there is of it, is of the prickly variety, which I assume is meant to deter predators as much as possible given this harsh environment. One shrub stands out. It is about a foot and a half high, light brown and round with a flat top. From a distance it appears to be formed from a tightly patterned weaving of stems. On closer examination, I find the stems are composed of a dense configuration of two- to three-inch-long sharp thorns. Upon my return to camp I asked our very helpful host, Miguel Roth, director of the Las Campanas Observatory, what kind of plant this is. He said he did not know the technical name, but it is locally called the "mother in law" seat. Enough said.

Walking back to the lodge I pass by the parking area in front of it and notice a sign, "Parking—Astronomers." Where else in the world would parking spaces be set aside exclusively for astronomers?

At the meeting about the GMT, we review the progress of the partnership. An impressive group has signed up, including the Smithsonian, to build this new telescope. It will allow humans to view deep into space and time and explore the origins of the universe in ways never before possible. The GMT will allow imaging of newly discovered planets that are smaller than the earth. New concepts of "dark matter," which forms more than 80 percent of the mass of the universe, will be developed. Work on the project is proceeding on all fronts and the first of the large mirrors has been built at a special facility that lies under the football field of the University of Arizona. The Smithsonian will need to raise significant funding over the next decade to meet its share of the cost, but the concept has been approved by our Board of Regents and we are committed to it to insure that our long-standing strength in astrophysics and astronomy is not diminished.

Later that evening we have a dinner with the observatory technical staff who run the telescopes and the facilities. This is not only a fine meal, but allows us to converse with staff members who are all native Chileans.

From dinner we head for the Magellan telescopes again for a viewing of the stars. It is pitch-dark on the mountain top and the sky is cloudless, perfect for astronomy. The doors of the observatory are open and the big telescope is rotated into position for viewing.

Miguel has placed an eyepiece on the 6.5 meter Magellan/Clay telescope which allows us to see some amazing sights! First, we see the planet Saturn in our own solar system with its rings viewed sideways as thin bright slivers in the dark sky along with its five surrounding satellites. Then we moved on to the star Eta Carinae, a massive star 7,500 light years distant from Earth. The light that we saw tonight left the star about 7,500 years ago! This star had an eruption about 160 years ago (our time on Earth, around the year 1849) that formed a bright 'nebula' of gas that appears as two large spheres emerging in opposite directions from the star. It was impressive that we could see these so well tonight with sight of only 0.4 arcsec (a very small measure) on the sky! We turned to Omega Centauri—one of the most massive clusters of stars in our galaxy. The field of the telescope was filled with bright stars. Astronomers believe this may have been another small galaxy absorbed by our own because it contains stars of different compositions.

Our time is up, and we turn over the telescope to the astronomer who has work to do for the rest of the night. For a brief moment of time we have experienced the excitement of astronomy. It was truly a beautiful night here at Las Campanas.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)