Day 5: Bird Watching and Animal Tracking

Living among the African wildlife, Smithsonian researchers are busy studying the symbiotic relationships between flora and fauna

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Smithsonian-Secretary-superb-starlings-631.jpg)

June 16, Mpala Research Centre, Laikipia, Kenya. Weather—cool breezes, clear, sunny.

There are more than 300 species of birds on the Mpala Ranch and it is easy to appreciate their beauty and vitality. The bird feeder on our porch serves up a bit of theater as it attracts a raucous crowd who jockey for a turn at the feeder. The joker in the deck is a vervet monkey who also likes the fruit the staff puts out. He has to be shooed off before he cleans out the feeder.

The feeder attracts small and large customers. The smaller birds include the yellow-fronted canary and the sparrow weaver. They have to compete with the larger superb starlings, doves and hornbills.

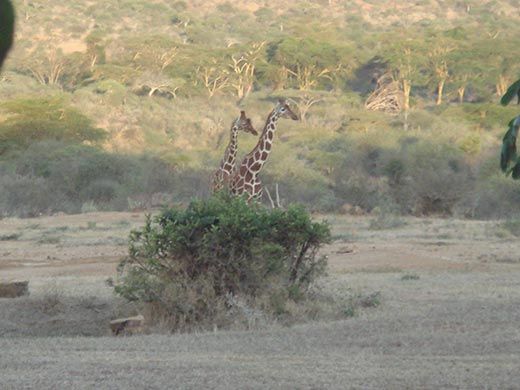

(Interruption—while writing this on the back porch, two beautiful giraffes stroll up to watch the humans. They have a long look before loping off to more open territory.)

For those of us from urban areas it may be hard to imagine a “superb” starling, but these fellows deserve the name—they are plumed with iridescent blue feathers on their backs and orange/brown feathers on their breasts. The doves are much like those we know in the United States but the males have red colorings around the eyes. Hornbills are large gregarious birds that mate for life. The pair that visit the feeder not only enjoy the food but also seem expressively curious about the humans watching them.

Other birds that frequent the grounds include the beautiful marica sunbird that feeds on nectar from long-throated flowers. Common guinea hens move in flocks kicking up dust as they scour the ground for insects. Less seen and shyer birds include the hadada ibis and the lovely black-crowned tchagra.

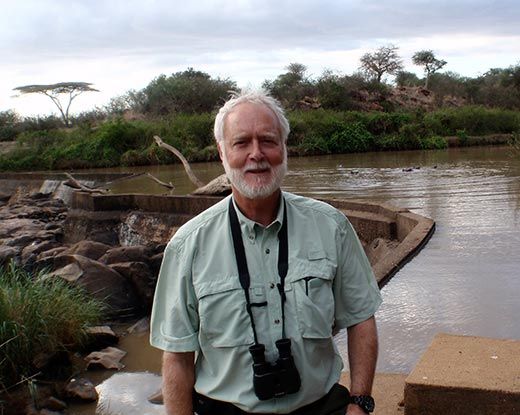

It is tempting just to sit on the porch and watch the parade of birds and animals that just show up. But, we use the early morning of this day for one more wildlife drive. A new addition to my list of animal sightings is the eland, another of the large number of grazing animals found here. The eland is a powerful animal with short horns that spiral out from the head.

Our drive takes us along a road between the river and a high ridge, a favorable haunt for raptors who feed on fish and land animals. Sightings include Verreaux’s eagle, a dark chanting goshawk, and an augur buzzard. All are beautiful creatures, including the augur buzzard, which looks nothing like its U.S. relatives, but more like a fish eagle.

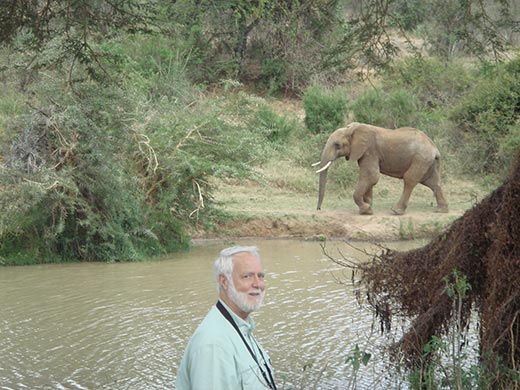

We also see impala, baboons, zebras, giraffe and waterbucks. There are also four or five groups of elephants, most with calves. We stop to watch the elephants and take a few pictures. Where the road takes us close to a group, the mother elephants become nervous, and let us know our presence is not appreciated with loud growling and shrieks and wagging of their ears. We move along rather than risk the wrath of the elephants.

After lunch we tour the “tented village,” an area used by up to 30 visiting students and their faculty advisors. This accommodation and the housing at the Research Centre is available for researchers from universities and other organizations in support of their investigations related to African wildlife and environmental issues, particularly those pertinent to Mpala. Along with the Smithsonian, Princeton University has been involved with Mpala since the Research Centre was formed, but faculty and students from many other universities take advantage of the opportunities offered here.

Late in the day a group of us have the opportunity to visit the field research site of Dino Martins, a Harvard University scientist who is studying the symbiotic relationship between various types of ants and acacia bushes. Dino is a native Kenyan who cut his research eyeteeth working at Mpala with the Smithsonian’s own Scott Miller. The acacia is the most commonly found plant found at Mpala, ranging in size from almost a groundcover to the size of small tree. . In all cases, the plant is equipped with long, sharp thorns to help protect it from the many grazing animals at Mpala. It also has another defense—the colonies of ants that live in the bulbous hollow knobs that form at the joints of the plant. Dino explains that the ants can be of many species, some very aggressive and some less so. The ants boil out of their homes at the first sign of any vibration or disturbance, such as a light tap with a stick, ready to defend their turf. The most aggressive ants will jump from the plant onto a human and their biting can cause considerable discomfort. In the course of his research, Dino has been bitten many, many times, but he seems to take it all in stride as he explains his findings with enthusiasm.

The ants help protect the acacia and in turn, the bush provides the ants with homes and food harvested from the inside of the acacia’s bulbous knobs.. This remarkable relationship between plant and ant is not yet fully understood and Dino is excited about his study. He notes that a fungus grown by the ants may have positive pharmaceutical applications. Dino also points out that in terms of sheer biomass, the cumulative biomass of ants at Mpala is greater than that from the combined weight of the humans and animals there.

It seems fitting that my last trip into the field at Mpala dwells on ants and the way in which they serve a crucial purpose in the ecosystem. From tiny ants to huge elephants, all are part of a complex web of life at Mpala and similar places that we do not yet fully comprehend. If we are to make the right decisions about this complex ecosystem in the future so that the great animals will survive, it must be based on the knowledge of how all the parts work together, and this is why research is essential for the future.

We close our time at Mpala with another enjoyable dinner with our colleagues and people we have come to admire. As the person responsible for the research enterprise, Margaret Kinnaird brings talent and grace to her work. As the manager of the ranch, and impresario of wildlife drives, Mike Littlewood brings a unique knowledge of Kenya, her people, animals and all things practical, such as how to drive a Land Rover at 50 mph over washboarded roads while avoiding goat herds. We have greatly enjoyed our time here and have memories we will not forget. We thank all of those who have contributed to this exceptional opportunity.

From Mpala, we head back to Nairobi where, on our last day in Kenya, we make courtesy calls on SI partners and others to say hello and hear from them their thoughts about the future of Kenya, its wildlife and the role of Mpala. Visits to Kenya Wildlife Service, the National Museums of Kenya, and the U.S. Embassy to meet with Ambassador Michael Rannenberger conclude our visit. It is clear that the presence of the Smithsonian Institution is an important element in bringing credibility and research expertise to the work done at Mpala.

Time to return to Washington. It will be a long flight, but the trip was truly worth the effort. We will have to make challenging decisions in the days ahead as to where and how the Smithsonian will apply its funding and effort, but being able to see places like Mpala firsthand will help guide our choices.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)