Deep in the Ndoki Jungle, A Few Sheets of Nylon Can Feel a Lot Like Home

The founding editor of Outside magazine explains why a tent is sometimes the difference between life and death

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/FOB-tents-631.jpg)

The Baka people of the Ndoki forest thought my “home” was “flimsy.” At least that’s the way the words were translated to me as the Baka milled about my tent and pinched the material, intent as fabric buyers in the garment district. “My home” wouldn’t be much protection against, say, a leopard. Forest elephants would walk right over it, and anything inside. Like me.

We were all at the start of a monthlong trek through the Ndoki forest in northern Congo. Our job was to assist a scientist who would inventory the animals here in the watershed of the Congo River, a huge rainforest with a significant population of lowland gorillas, as well as innumerable elephants, leopard and antelope. And I had chosen to bring along a shelter that the Baka thought no more substantial than a spider’s web.

Well, I would try to pitch my flimsy home off animal trails but close enough to the others so that they could hear me scream. I’d sleep with one ear open. Gorillas don’t attack sleeping humans. The elephants, I knew, crashed through the forest, felling trees before them. You could hear those guys coming. The leopards made an odd humming sound. At least that is what the Baka told me. I never actually saw a leopard, but I noticed some kills stashed in the branches of trees and I heard humming at night.

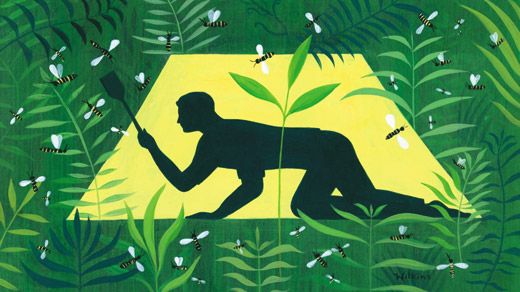

The truth is: I wasn’t much concerned about big game. I live in Montana and have spent plenty of nights wide awake in my tent wondering whether that...sound...might be a grizzly. No, my worries were smaller. The Congo forest is home to uncountable numbers of bees. Honeybees, “killer” bees, long skinny bees that looked like wasps and a stingless variety called meliponini, which materialized in vast unbearable clouds. They were tiny, the size of a midge, and they crawled up your nostrils and you swallowed dozens of them with every breath.

Which is where a “flimsy home” came in handy. The Baka, who could build a substantial lodge out of bush material in the time it took me to pitch my tent, had no protection from the melipons. Or the stinging bees, which didn’t light on them often, in any case.

The bees didn’t sting when we were walking. They nailed me only when I stopped. I was getting stung a dozen times a day. Until I figured out how to deal with bees.

I learned to set up my tent immediately when we stopped for the day. There I sulked until the exit of the bees at full dark. The Baka, who seemed impervious to bee stings, were having a merry time. I had to wait to join in the festivities. And then, after dinner, I walked back to my flimsy home and lay there in the silence while...things...moved about in the bush. I felt unaccountably safe, like a toddler who thinks that when he covers his eyes, he is invisible to you. Such were the comforts of my flimsy home.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.