Deep in the Swedish Wilderness, Discovering One of the World’s Greatest Restaurants

At Fäviken, Chef Magnus Nilsson takes locavorism to an extreme by relying on subarctic foraging, farming, hunting and preserving traditions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/faviiken-scallops-i-skalet-ur-elden-main.jpg)

Clap-clap!

Chef Magnus Nilsson slaps together his bear-paw-sized hands, announcing his presence in the cabin-like space that serves as his dining room. Bunches of herbs hung to dry and edible flowers adorn the sparse walls, and meat and fish hang lazily from the ceiling as they cure. Tonight—a Tuesday in early July—the restaurant is at full capacity, seating 16 guests around a handful of sparse wooden tables.

“Here we have scallop ‘i skalet ur elden’ cooked over burning juniper branches,” Nilsson announces. Staff members deliver two pink-shelled scallops nestled on a bed of smoking moss and juniper to our table. The dish smells like Christmas at the beach. “Eat it in one bite, and drink the juice, ok?” Nilsson says.

The scallops—taken from the fire in the kitchen downstairs no more than 90 seconds earlier—open to reveal a pearly dollop of meat marinating in its own murky juices. I place the entire succulent morsel into my mouth with my fingers, and then slurp down the broth, as instructed. I’m rewarded with flavors of the Norwegian Sea: briny, salty and sweet.

This is Fäviken Magasinet, a restaurant located in the heart of northwest Sweden’s forested wilderness, Järpen. The region is roughly the same size as Denmark, but with only 130,000 residents. The restaurant’s location requires hopeful patrons to embark upon a pilgrimage of sorts. You can either take a car or train from Stockholm—a 470-mile journey—or jump on a quick flight to Östersund, a town about an hour and a half east.

Described by Bon Appétit as “the world’s most daring restaurant,” Fäviken’s extreme remoteness, unique dishes and strict regime of locally hunted, foraged, fished, farmed and preserved ingredients quickly began earning the restaurant and its young chef notoriety when he took over as head chef in 2008. Just four years later, Fäviken landed 34th place on the British magazine Restaurant’s coveted World’s 50 Best Restaurants list, on which the judges pose: “Is this the most isolated great restaurant on the planet?”

A journey north

I enjoy food, but would hesitate to call myself a true foodie. I haven’t been to Per Se (#11 on the Restaurant’s list) or Eleven Madison Park (#5), both in New York City, and I wouldn’t plan a trip to Denmark just to eat at Noma (#2). Fäviken, however, was different.

I first learned about Nilsson in a short blurb in TimeOut New York, in a review of his recently published cookbook cum autobiography, Fäviken. The “uncompromising young chef (just 28),” TimeOut wrote, “has been pushing the boundaries or hunter-gatherer cooking” in a “groundbreaking restaurant in the middle of nowhere.” Something about sipping a broth of autumn leaves in the Swedish woods deeply appealed, and I began looking into this strange place. Seeing the restaurant’s website—a panorama of the property’s 19th century converted barns, that changes with the seasons—solidified my next vacation plans.

Nilsson grew up near Fäviken’s property, in a tiny town called Mörsil. Though he fondly recalls spending time in the kitchen with his grandmother, the young Swede originally aspired to become a marine biologist. But gastronomy trumped ichthyology, and Nilsson eventually landed spots cooking under three-star Michelin chefs in Paris. But he returned to Sweden after his Paris sojourn and tried pursuing his own kitchen aspirations, his efforts fell flat. His dishes were only poor imitations of his mentors’ creations. Discouraged, he stopped cooking and decided to become a wine writer instead.

This circuitous path led him to Fäviken. In 2003, the restaurant’s new owners recruited Nilsson to organize their wine collection under a three-month contract. At the time, the restaurant relied mostly upon products imported from around Europe, and mainly served a surplus of guests arriving for an annual game fair held on the property each July. “Nope, I never though I’d come back here,” Nilsson later tells me of his rural home region. Gradually, however, he began finding himself spending more and more time in the restaurant’s small kitchen. He also took to roving the forests and fields of Fäviken’s 24,000-acre property, collecting interesting edibles he came across and experimenting with recipes in his spare time. Months melted into years, and in 2008 Nilsson began officially running the restaurant. “That’s how it happened,” he says. “I went back into the kitchen again.”

Reaching that fabled kitchen, however, is no easy task. My boyfriend Paul and I opted to fly through Östersund as we took off early in the morning from sunny Stockholm, leaving behind perfect summer-dress weather. As we slid through the layer of thick clouds obscuring Järpen, a new landscape materialized. Dense swaths of evergreen forest—broken only by the occasional cabin or farm—blanketed hills and encroached upon expansive black lakes. When we touched down at the tiny Östersund airport, a large hare sprinted out onto the runway, racing the plane for a few brief moments. It occurred to me that we were dealing with something entirely different than Stockholm’s outdoor cafes and glimmering waterside promenades. This was the North.

A traditional palate

Up here, Nilsson explains, incorporating the land into daily eating and living is second nature. October’s chill traditionally marks the end of fresh ingredients until spring’s thaw renewed life in April. Studious planning and preserving were essential for a subarctic household’s survival. Even now, some of those traditions have lingered on. If residents don’t hunt or fish, they know someone close to them who does. Picking berries for jam, gathering mushrooms for preserving, pickling homegrown vegetables and curing meat are normal household activities. While high-end restaurants in the world’s metropolises may boast about the novelty of their handful of foraged ingredients, here it is natural and unforced. “It’s just part of what people do, even if they don’t realize it,” Nilsson says.

Nilsson, too, abides by these traditions. Only a few ingredients—including salt, sugar and rapeseed oil from southwest Sweden, Denmark and France, respectively, and fish from Norway—do not originate from the immediate vicinity. The repertoire of wild plants he regularly harvests from around the property number around 50, ranging from hedgehog mushrooms to Iceland moss, from wormwood to fiddlehead ferns. He also hunts, as attested by the paper-thin slices of wild goose served during my visit. The bird is coated in an insulating layer of sea salt, then hung in the dining room to dry for several months before appearing on our plates. Likewise, he slaughters his own livestock and uses nearly every part of their bodies. Fried pigs head balls sprinkled with pickled marigold petals, for example, appear on the menu this summer. “Sometimes, when I look at the way people treat meat inefficiently . . . I think there should be some kind of an equivalent to a driver’s license for meat-eaters,” Nilsson writes in his book.

In the winter, Fäviken hunkers down and relies upon a store of pickled, cured, dried and fermented produce and meat to feed its guests. “It’s so lovely in the winter, so dark,” says Sara Haij, who works at the restaurant as a server-cum-hostess-cum-travel agent. “But the snow lights it up. And in February and March, the northern lights peak.”

During these nearly sunless months, some vegetables, including cabbage and kale, can remain in the earth or buried under snow. As long as temperatures stay below freezing (not a lot to ask in Järpen, where winter temperatures regularly dip to -22˚ F) the vegetables will keep.

For fermenting, Nilsson largely relies upon Lactobacillus bacteria, whose use in preservation spans centuries and cultures, from kimchi in Korea to beer brewing in ancient Egypt. Pickling, on the other hand, depends upon lowering the osmotic pressure in the cells of the ingredient—beets, berries, roots—with salt, then adding a solution of vinegar and sugar, which easily penetrate those emaciated cells. The flavor of pickling—specifically with white alcohol vinegar—Nilsson writes in his book, is “one of the original tastes of Scandinavia.” Nilsson, not surprisingly, also makes his own vinegars, including a “vinegar matured in the burnt-out trunk of a spruce tree.”

Many of Nilsson’s preserved products are stored in his cellar, a cubby hold dug out of the side of a hill, across from the restaurant. Here, curious diners can also take a peep at his ongoing experiments, where jars of pickling wildflowers, submerged sprigs and even bottled curios of seafoody flesh line shelves on either wall. The space seems deceptively small, but, starting in the autumn, crates of dormant roots are buried beneath its sandy floor. In spring, even in the light-deprived environment, what’s left of these roots often begin producing pale shoots that “taste like the very essence of the vegetables from which they sprout,” Nilsson writes.

A day at Fäviken

This, however, is summer, when the sky never fully darkens and the produce is at its peak. We bump down a gravel road several hours after leaving the airport (obligatory stops were made at a moose petting farm and a hippie-like restaurant commune in Nilsson’s hometown that he recommended), unsure of whether we should have turned left at that last lake, or gone straight over an old bridge. Here, cell phone GPS guidance is out of the question. A break from the trees, however, finally reveals our destination: across a glacial lake, Fäviken’s red barn stands out against the green.

Wildflowers and herds of free-range sheep blaze by on our final approach, and not even a cold, persistent sprinkling of rain can put a damper on this triumph. Through a window on the converted barn, we can see the chefs are already bustling about the kitchen, though it’s just 2:00 and dinner doesn’t begin until 7:00. Karin Hillström, another Fäviken employee, bursts out to meet us with a welcoming smile, ushering us into a pine log room (an original from 1745) filled with lambskin sofas and a wildflower-bejeweled bar. Hillström assigns each party for that evening’s dinner an arrival hour—we were 3:00—staggered to allot time for an individual welcome and a private session in the sauna. A fire warms the room, and Nilsson’s big, wolf-fur coat hangs on one wall like a trophy. Robert Andersson, the sommelier, wastes no time uncorking the first bottled aperitifs.

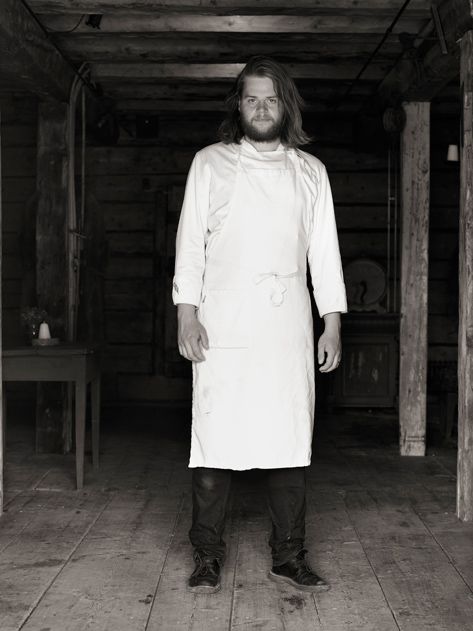

Nilsson soon emerges from the kitchen wearing his chef’s whites, politely greeting us before Hillström shows us to our room, which is marked not with a number but a hand-painted portrait of a black bear. Because of its remoteness, many guests chose to stay the night at the restaurant’s small guesthouse. The sauna, just across the hall, is fully stocked with champagne, regional beer and local berry juice, along with “some snacks” of homemade sausage and hairy pickled turnips, hand-delivered by one of the chefs. From the delicate bouquets of wildflowers to the slate-slab tabletops, Fäviken seems to epitomize attention to detail.

Feast at the farm

Tonight, we’re sharing hors d’oeuvres with a British couple, Rachel and Matt Weedon. Outside of Norway and Sweden, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and the U.S. supply the most visitors. They met in the restaurant industry “many moons ago,” spent their honey moon eating their way through San Francisco and Napa Valley, and now travel twice a year on food holidays. “In the chef world, this guy [Nilsson] is talked about so much,” says Matt, who runs the kitchen and manages the farm at Fallowfields, a restaurant in Oxfordshire. “I heard about him, bought the book, and said OK, we’re going.”

We nibble on crispy lichens dipped in lightly soured garlic cream (the delicate growths nearly dissolve in the mouth), and pop tarts of wild trout’s roe served in a crust of dried pigs blood (oddly sweet, with juicy bursts of fish-eggy saltiness), then proceed upstairs to the spartan dining room. Tables are scattered throughout the room, seating a maximum of 16 guests and spread far enough apart so that each couple or group feels almost as if they are enjoying a private meal. Andersson pours the first wine—mead, actually—made locally and “just like the Vikings used to drink.” Rather than match wines for all 14 of the main courses, Andersson chooses five eclectic pairings that can complement a number of dishes. “I like to drink wine, not taste it,” he explains.

Menu highlights of the evening include a fleshy langoustine impaled on a twig and served with a dollop of almost-burnt cream that Nilsson instructs us to apply to each bite of the creature. A festive porridge of grains, seeds, fermented carrots and wild leaves comes with a glass teapot that is brimming with living grasses and moss rooted atop a bed of moist detritus. Andersson pours a meat broth filtered through this bushy assembly into our porridge; when he removes the teapot, a tiny, squirming earthworm is inadvertently left behind on the table. For a dish of marrow served atop diced raw cow’s heart with neon flower petals, the chefs carry a tremendous bone into the dining room, then proceed to saw it open like a couple of lumberjacks to get at the fresh, bubbling essence within. The butter served throughout the meal—simply the best I have ever tasted—comes from a little cottage nearby, where it takes three days to collect enough milk from the owner’s six cows to churn out a single batch.

The most standout dessert of the evening is an egg yolk, preserved in sugar syrup, plopped next to a pile of crumbs made from pine tree bark. We diners are instructed to mash these ingredients into a sticky, rich dough, while the chefs turn the clacking crank of an old-fashioned ice cream maker, then spoon out portions of the icy, meadowsweet-seasoned goodness alongside our fresh dough.

We round out the evening by sipping on sour cream and duck egg liquor, and sampling simple sweets—dried berries, sunflower seed nougat, pine resin cake—laid out in a jewelry-box assortment, like a child’s prized collection of marbles and shells. Only the tar pastilles, which taste like a mix between chainsaw exhaust and chimney soot, fail to deliver. The final, optional offering is a strip of chewing tobacco, fermented for 70 hours and issued with a warning that the nicotine could prove too much for guests who aren’t used to it. “This smells like my dad,” I overhear one patron say.

A master of the craft

The process of creating these exceptional dishes, Nilsson explained earlier that afternoon, is like any other profession involving craftsmanship. “You must first perfect your techniques so they don’t get in the way of your ability to create things,” he says. At this point, he says, creation comes to him intuitively—“It just happens, I just cook”—though he is always looking to innovate and improve. In his book, he elaborates: “Throughout my career so far, and I hope for the rest of my life, I have always tried to become a little bit better at what I do every time I do it.”

As such, after the meal Nilsson stops by each table, asking his patrons to comment on dishes they did or did not like. The dishes, he says, may evolve significantly on a day-to-day basis or may remain static for months or years on end. It all depends on the season, the produce and “the mood of us all, and what we do here.” For now, Fäviken is a dynamic work in progress, though this unique project in the Swedish woods is by no means indefinite.

“I’m sure it will be very definite when we run out of interesting things to do,” Nilsson says. “But there’s no end date, it’s just something you feel when it’s done.”

Fäviken accepts dinner reservations for up to six people, which can be booked online three months in advance. Dinner is served Tuesday to Saturday, and hotel reservations can be made at the time of booking. Price per person for food is SEK 1,750 (approximately $268 USD); for drinks, including aperitifs and digestifs, SEK 1,750 ($268); and SEK 2,000 ($307) for accommodation for two, including breakfast.

Details on travel to Fäviken by car, train, plane or cab can also be found on the website. SAS flies daily between Stockholm and Östersund, and between Trondheim and Oslo.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)