Derby Days

Thoroughbreds, mint juleps, big hats—the Kentucky Derby’s place in American history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/derby631.jpg)

"During Derby Week, Louisville is the capital of the world," wrote John Steinbeck in 1956. "The Kentucky Derby, whatever it is—a race, an emotion, a turbulence, an explosion—is one of the most beautiful and violent and satisfying things I have ever experienced."

For generations, crowds have herded to Churchill Downs racetrack in Louisville on the first Saturday in May, with millions more tuning in to live television coverage. The Kentucky Derby, a 1-1/4 mile race for 3-year-old Thoroughbred horses, is the longest continually held sporting event in the United States—the horses have run without interruption since 1875, even during both World Wars.

But for its first few decades, says Jay Ferguson, a curator at Louisville's Kentucky Derby Museum, "the Derby wasn't the horserace. Back around the turn of the century there were three horses in the race, and Churchill Downs had been losing money for every year it had been in existence." It took savvy marketing, movie stars, southern tradition and luck to turn what could have been just another horse race into what many have called "the most exciting two minutes in sports."

Col. Meriwether Lewis Clark (grandson of explorer William Clark, of Lewis and Clark fame) founded the track that would later become known as Churchill Downs in 1874, on 80 acres of land owned by his uncles, John and Henry Churchill. The first Kentucky Derby, named for England's Epsom Derby race, was one of four races held on May 17, 1875, before 10,000 spectators. A chestnut colt named Aristides won the top prize of $2,850.

Though Churchill Downs continued to draw crowds, it was plagued by financial troubles for its first three decades. In 1902, as the track was in danger of closing, the Kentucky State Fair used Churchill Downs to stage a collision of two locomotives. Col. Lewis, who committed suicide in 1899—in part because Churchill Downs had proven a disappointment—had had high hopes for Kentucky racing, but for its first few decades the Derby remained a minor event.

Things began to change, however, in October of 1902, when a group of investors led by Louisville businessman Matt Winn took over the failing operation. "Winn was a natural born salesperson," says Ferguson. "It's pretty much Matt Winn who made the Derby what it is." In 1903, thanks to Winn's marketing efforts, the track finally turned a profit. Over the next several years, Churchill Downs underwent renovations, and Winn modernized and expanded the betting system.

The Derby began to attract wider attention in 1913, when a horse named Donerail, given odds of 91.45 to 1, became the longest shot ever to win the race. The next year, Old Rosebud set a Derby record of two minutes and three seconds, and in 1915 a celebrated filly named Regret became the first of only three females to win the Derby. Her owner, wealthy businessman Harry Payne Whitney, came from the East Coast racing establishment, and his horse's victory popularized the Derby to fans outside Kentucky.

These landmark wins helped boost the Derby to national prominence, but the rise of mass media is what gave the race the hype it has today. By 1925, fans could follow the contest live on the radio, and movie audiences could watch news reel replays. In 1949, a local television station first broadcast the Derby in Louisville, and three years later it was televised nationally. To glamorize the Derby during the 1930s and 40s, Matt Winn invited celebrities like Lana Turner and Babe Ruth to watch from the grandstand. The presence of the rich and famous grew to be a Derby tradition, and the box seats they occupied became known as "Millionaire's Row."

Winn led Churchill Downs until his death in 1949, and by then the Derby had become not just a Kentucky institution but a national event. In 1937, Winn, along with four of the Derby favorites for that year, appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

It's the race's signature traditions, however, that make the Kentucky Derby interesting even to people who don't have anything riding on the winning horse. Mint juleps, big hats and red roses have become almost as essential as the horses themselves. A concoction of sugar, water, mint and Kentucky bourbon, the famed julep dates back to the beginning of the race—founder William Clark, says Ferguson, "was fond of drink." Matt Winn formalized the julep's status in 1938, when Churchill Downs began selling commemorative julep glasses. Today, Derby-goers consume some 120,000 juleps.

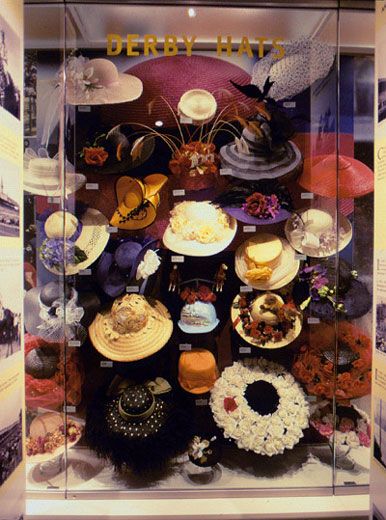

Big hats also date back to the race's early years. Ladies attend the races decked out in their finery, with hats that can be fancy or fanciful. Along with the standard wide-brimmed chapeaux decorated with ribbons and flowers, the Derby Museum has on exhibit a hat made out of coffee cans arranged to look like a horse's head.

Gentlemen prefer the simpler straw boater hat, but that too can also include accessories like tiny horses and roses, the Derby's official flower. The race earned the nickname "Run for the Roses" (coined by sportswriter Bill Corum in 1925) because of the roses that have been draped over the winning horse since 1896. Today the official garland of 554 blooms is hand-made at a local Kroger grocery store the afternoon before the race.

This year on May 5, Churchill Downs will be "jam-packed," says Ferguson. "Unless you have a seat, there's no guarantee you will see a horse or a race." But for the 150,000 people expected to attend, the crowds, the dust (or mud, if it rains), the expense (general admission tickets are $40, with hard-to-get season boxes going for up to $2,250) and the unpredictability are all worth it.

The Kentucky Derby is the 10th of 12 races on Derby Day, held after several hours of wagering and julep-drinking. The crowd begins to buzz as the horses walk from their barns into the paddock, where they're saddled and mounted. The horses step onto the track to the cheers of a crowd the size of Dayton, Ohio, and as they parade around the first turn and back to their gates, the band strikes up "My Old Kentucky Home."

As the horses get stationed behind the starting gates, the crowd quiets down, but cheers erupt again as the bell rings, the gates open and the horses gallop out. "The whole place just screams—it's an explosion of noise," says Ferguson. "When the horses are on the back side the anticipation builds, and as they come around home it's a wall of sound." Just thinking about it, he says, "I'm getting goose bumps. And I'm not kidding."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)