The underwater caves of the Yucatán Peninsula are a window to the distant past. Through two million years and over multiple glaciation cycles, these caves have been transformed. When the sea level was high, the caves flooded, and their reach expanded.

During the ice ages, the caves dried out as the sea level dropped, and the seeping water from the surface decorated the caverns with deposits such as stalagmites and stalactites, collectively known as speleothems. Then, with the next cycle came higher sea levels again, flooding the caves and preserving in time the speleothems and everything else with them.

I have been diving the unique submerged landscapes of Mexican cenotes, or sinkholes, for almost ten years, exploring their dark, flooded tunnels and capturing their secrets. The last time the shallow caves on the Yucatán Peninsula flooded was around 8,000 years ago, which means that every diver in these caves travels back in time to a prehistoric age. The paleontological and archaeological remains preserved within them would disintegrate at the surface, which makes these caves a perfect time capsule.

How Mexico’s cenotes came to be

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/39/8f399fc2-5560-45d8-900f-00b07c99e2c2/martin_broen_page36.jpg)

This underworld is formed by a massive underground aquifer in the northern Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. It is accessible by cenotes that connect the surface of the Earth to the longest underground river systems in the world. Here, water doesn’t accumulate on the surface as rivers, but instead gets absorbed through the porous limestone to flow within underground tunnels. Much as our blood vessels send life-sustaining fluid throughout our bodies, these tunnels convey the precious water that sustains all life in this region. It is no wonder that cenotes were considered sacred by the Maya.

The Maya established their civilization on the Yucatán Peninsula about 4,000 years ago. In order to thrive, they needed to settle close to a freshwater source. All of their largest settlements on the northern part of the peninsula—including the famed Chichén Itzá—were built beside cenotes. During the region’s dry season, cenotes were the only source of water; therefore, the sinkholes were not only a fundamental part of Maya life but also a place for worship and rituals related to rain, life, death and rebirth.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/90/79/90790f3b-89bf-400f-bb9d-1ec7163b56a7/martin_broen_page64.jpg)

Each Maya d’zonot (the Maya word from which the word cenote comes from) was an entrance to the mystical underworld called Xibalba, where various deities and supernatural beings resided. It is a mysterious and powerful realm associated with death, a portal to a domain where ritualistic offerings honored both the gods and the deceased and sought protection and guidance for the living. Living within, and the protector of this underworld, was Chaac, the god of rain, fertility and agriculture. He was an important deity in Maya mythology, as rain was vital for the success of crops and the well-being of the community.

Beneath the cenotes, deeper in their caves, artifacts and human remains from the Maya civilization have lain undisturbed for centuries and can be seen by explorers. But these are not the only indicators of human presence. While the Maya settled the region only a few thousand years ago, evidence found in the cenotes points to human settlements in the area dating back more than 13,000 years. These finds challenge the accepted notion of when our ancestors first crossed into America via the Bering Land Bridge between Siberia and Alaska during the last ice age.

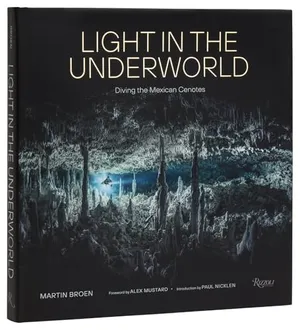

Light in the Underworld: Diving the Mexican Cenotes

An immersive journey into a natural wonder—the underwater caves and cenotes of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, a destination very few divers have ever reached.

These ancient hunter-gatherers also depended on the cenotes as a water source, and probably for shelter as well. Back then, the cenotes were much drier, with the water level some 300 feet below current-day levels. The ancient inhabitants had to venture deep into the caves to access the water, crossing paths with huge prehistoric animals from the late Pleistocene—now long extinct—that also sought fresh water.

Finding Maya artifacts and human remains

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/51/53/51530ab9-54e0-431f-a9b7-ee6e1c23d66a/martin_broen_page142.jpg)

It’s challenging to put into words the raw and profound sensation that accompanies encountering a human skull in the darkness of the flooded caves. Long before I recognize a skull as mere remains, I can feel its gaze upon me from the shadows, a haunting presence that defies description. Particularly in the area of the Ring of Cenotes, many sacrificial cenotes hold skulls of the higher-ranking Maya families. Along with modified front teeth to host ornaments, these skulls were artificially deformed to create a physical distinction. The higher-ranking Maya used different techniques to shape their children’s skulls, creating an oblique deformation, which made their heads look longer than the average Maya’s. Said to resemble a jaguar’s head, this shape was a symbol of power. Also rare sightings for cave explorers are sophisticated Maya paintings on cave walls close to the entrances of cenotes. Depicting wars, animals, gods and stories, these treasures can be forever lost once submerged, washed away over time.

Long before the Maya settled in the area, the first Homo sapiens crossed into America over the Bering Land Bridge at least 25,000 years ago. They made their way down to South America and arrived on the Yucatán Peninsula at the end of the last ice age around 13,000 years ago. There they used the caves to extract water and minerals, to find shelter, and to bury their dead. While it is typically hard to find remains of these hunter-gatherers on the surface of the Earth, evidence of early human presence was preserved in these caves from before the last time the caves flooded. That evidence gives us clues to understanding early humans’ biology and even their social interactions.

Within the flooded caves it is common to see purposely broken formations that create passages through the tunnels, and even cairns—made of piles of rocks or broken speleothems—placed at the junctions of tunnels to navigate the intricate cave labyrinths. Early humans also excavated rocks and mined red ocher using only Stone Age tools and their mastery of fire. They used the ocher to decorate objects for personal ornamentation and burials. They also decorated the caves with multiple art forms, from paintings on the walls to sculptures. A well-known example is the figure of a woman at the entrance of Cenote Dos Ojos; while it was not sculpted as such, it is a carefully selected speleothem that resembles the silhouette of a woman and was intentionally exhibited on a pedestal to decorate the cave entrance, evidence of paleoart from more than 8,000 years ago that anyone can visit.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7e/c4/7ec494ec-ea5e-4be9-9064-a5a39e210a8d/martin_broen_page13.jpg)

Diving for fossil evidence of extinct megafauna

As if they were corridors of a museum, the submerged passageways of these time capsules also offer divers the opportunity to uncover exquisitely preserved fossils of diverse creatures—most of which are now extinct—that once inhabited the Yucatán during the late Pleistocene.

Following the cataclysmic impact of the Chicxulub asteroid 66 million years ago, which marked the end of the dinosaur age, mammals began to dominate the lands once ruled by dinosaurs. Over time, North and South America underwent distinct evolutionary trajectories. However, around 2.7 million years ago, the formation of the Panamanian land bridge facilitated a pivotal event: the Great American Biotic Interchange.

During this exchange, North American fauna migrated southward, including large mammals called megafauna, like saber-toothed cats, lions, gomphotheres (related to modern elephants), horses and camels. Meanwhile, South American megafauna moved northward, including giant ground sloths and glyptodonts (enormous armadillos). This monumental event significantly influenced and sculpted the ecosystems and biodiversity of both continents, affecting the composition of species and ecosystems we see today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/26/7c267208-c0f6-4589-9e6f-1ca9c6c34347/martin_broen_page110.jpg)

The thrill of exploring the underwater caves of the Yucatán is heightened upon uncovering the fossilized remains of these long-extinct megafauna. Visualizing these colossal creatures coming to life right where you are diving, in what was once a prehistoric cave that had been frozen in time by these waters, is like being teleported back to their era, immersed in a thrilling journey through time. How their fossils came to be submerged underwater can be easily imagined. With the water level during the last ice age up to 300 feet lower than it is today, these animals had to venture down dark, dry cave passages to reach drinking water, sometimes surprisingly far away from an entrance. Trapped in sinkholes or lost within labyrinthine passages, these animals died, and their remains became fossilized and preserved by rising water levels.

Among the many extinct species that lived in this region are members of the family Megalonychidae (including the genus Megalonyx, Greek for “large claw”). Fossils of these giant ground sloths are commonly found in the caves, as they probably took refuge within them, such as members of the genus Xibalbaonyx (“great claw of Xibalba”), a polar bear-sized ground sloth with big claws that measured up to 12 feet in height and weighed nearly a ton. They are joined by members of related families, including the genus Nothrotheriops, a grizzly bear-sized mammal that reached five feet tall and weighed 1,000 pounds.

Representing archaeological and paleontological marvels, the fossils concealed within the caves constitute genuine treasures, allowing for teams of specialized scientists to explore these wonders, aiming to unravel scientific enigmas, construct hypotheses and shed light on the mysteries that shroud our planet’s history.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/59/00/59008b60-1dd4-463c-9919-470052ade97d/martin_broen_page4.jpg)

Many more mysteries to be solved

There’s a symbiotic relationship between the passionate and technical cave explorers who investigate every hole in a cave in their free time (and just for fun) and those in the scientific community who want to study these prehistoric materials but cannot reach where they’re hidden in the underwater darkness. This relationship of discovery and research has already provided evidence of many newly discovered extinct species, as well as ancient humans who had vanished for millennia, a relationship that could be fostered even more by leveraging the world-class level of the dive explorers in the area. After all, the majority of these secrets remain yet to be discovered!

The caves also hold evidence that could solve a prehistoric murder mystery. After the Great American Biotic Interchange, these megafauna species coexisted in this region for hundreds of thousands of years and through multiple ice age cycles, until their abrupt extinction more than 10,000 years ago when a new species arrived on the Yucatán Peninsula: Homo sapiens.

After humans arrived in the region, many genera of large mammals became extinct. There are different ways to explain this mass extinction event. One leading hypothesis states that the already reduced populations of those animals, stressed due to the changing climate after the latest ice age, were hunted to extinction by the humans. These big mammals, which needed a long time to become sexually mature and had slow reproduction rates (up to 22 months), were particularly vulnerable to this new threat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/27/75/27752fce-4a20-463b-85b6-eadaca0d3fdb/martin_broen_page37.jpg)

Among the fossils preserved within the flooded caves, I have witnessed many examples indicating that these extinct species had been hunted and eaten by our predecessors, such as preserved megafauna bones exhibiting cut marks from human-made stone tools, the repetitive marks showing the methodical action taken to remove flesh from the bone. Also noted are perforations on fossilized bones inflicted by projectiles, extinct animal remains beside cooking pits with bones in them, organized piles of bones, and burn marks on animal fossils inside the cave. Indications such as these have been found at cave depths that correspond to the time horizon when humans and the now-extinct animals coexisted and within areas that also exhibit indications of the kind of sophisticated social organization required for early humans to hunt these big creatures, like the mining of red ocher.

The hypothesis of the Paleo-Americans overhunting these species to extinction still needs to be validated, but it is undeniable that these caves protect invaluable material for scientists to study, information that will help us understand our past—and hopefully inform our future.

Adaptation from Light in the Underworld: Diving the Mexican Cenotes by Martin Broen (Rizzoli New York).

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1000x662:1001x663)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/59/44/5944fdd6-8215-4a86-854f-782ec0b2e58e/martin_broen_page22.jpg)