Dreams in the Desert

The allure of Morocco, with its unpredictable mix of exuberance and artistry, has seduced adventurous travelers for decades

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/morocco_medersa.jpg)

Curled up under blankets inside my goat-hair tent, I thought I was settled in for the night. But now, drummers are beating a jazzy rhythm outside and women’s ululations pierce the night like musical exclamation points. The Brides’ Fair at Imilchil, Morocco’s three-day Berber Woodstock of music, dancing, camel trading and marriages, is in full cry. Sleep? Out of the question.

Squeezing inside a large tent overflowing with revelers, I do my best to keep up with the crowd’s staccato clapping. A woman stands up, holding her skirts in one hand and swinging her hips alluringly to the beat. Another woman leaps up, dancing in mocking, provocative challenge. As the two of them crisscross the floor, the crowd and musicians pick up the pace. This spontaneous, choreographic contest makes me feel I’m being allowed a backstage glimpse into Berber sensuality. The women keep swirling as the drummers sizzle on until the music reaches fever pitch, then everyone stops abruptly as if on cue. Momentarily exhausted, dancers and musicians collapse into their seats, and the tent hums with conversation. Minutes later, the sound of distant drums beckons the merrymakers, who exit en masse in search of the next stop on this rolling revue.

In Morocco, there’s always something luring you to the next tent—or its equivalent. This unpredictable mix of exuberance and artistry has enticed adventurous travelers for decades—from writers (Tennessee Williams, Paul Bowles and William Burroughs), to backpackers and hippies, to couturiers (Yves Saint Laurent) and rock and film stars (the Rolling Stones, Sting, Tom Cruise and Catherine Deneuve). Morocco’s deserts, mountains, casbahs and souks have starred in such popular films as Black Hawk Down, Gladiator and The Mummy as well as such classics as Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much and David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia.

I was drawn to Morocco as well by its image as a progressive Muslim country, a staunch American ally since Sultan Sidi Mohammed became the first foreign ruler to recognize an independent United States in 1777. Since assuming the throne in 1999 on the death of his father, Hassan II, the young reformist king Mohammed VI, now 39, has helped spark a remarkable cultural revival. Tourists from America and Europe keep filling its hotels to wander crowded alleys, trek the Atlas Mountains, visit the Sahara and relax inside Marrakech’s palatial houses.

Westerners can hardly be blamed these days for being concerned about safety when traveling in parts of the Arab world. But the State Department, which alerts U.S. citizens to dangers abroad, has listed Morocco as a safe destination for years and continues to do so. Mohammed VI was among the first world leaders to offer condolences—and his assistance in rallying the Arab world to the war on terrorism—to President Bush after September 11. Moroccans have staged demonstrations in support of the United States, and American diplomats have praised Morocco’s cooperation.

A mere eight miles from Spain across the Gibraltar straits, Morocco, a long sliver of a country roughly the size of France, hugs the northwest corner of North Africa. The region and its native Berber population have been invaded by the usual suspects, as Claude Rains might have put it to Humphrey Bogart in the film Casablanca (shot not in Morocco but in California and Utah): Phoenicians, Romans, Carthaginians, Vandals, Byzantines and Arabs all have exploited Morocco’s geographic position as a trading link between Africa, Asia and Europe.

In the eighth century, Moulay Idriss, an Arab noble fleeing persecution in Baghdad, founded Fes as the capital of an independent Moroccan state. Nearly three centuries later, in 1062, a nomadic tribe of Berber zealots known as the Almoravids conquered Idriss’ descendants and established Marrakech as the new capital. In the 17th century, Moulay Ismail, a pitiless conqueror, moved the capital to Meknes and established the currently ruling Alaouite dynasty.

France and Spain both sent troops to occupy parts of Morocco in the early 20th century after a series of tribal conflicts. Under separate treaties, Morocco became a joint French-Spanish protectorate. During World War II, French Morocco fell under German occupation and Spanish Morocco was ruled by pro-Nazi Franco forces. After the war, nationalists agitated for independence, which was granted in 1956, a year after the return of the exiled sultan, who became King Mohammed V, the present king’s grandfather.

My first stop is Fés, where for the past two decades teams from Harvard, MIT, Cornell, UCLA and the Prince Charles Foundation have returned year after year to study the 850-acre medina (the walled old town), in an effort to save this vast honeycomb of medieval whitewashed houses from further decline. With financing from the World Bank, the city has inventoried its more than 13,000 buildings and restored 250 of them.

“The main problem is overcrowding,” says Hassan Radoine, codirector of the agency restoring the medina. “You find ten families living in a wonderful palace built for a single family.” As we squeeze through streets jammed with people, mules, carts and endless stalls of goods, Radoine guides me to the Medersa Bou Inania, a 14th-century school being meticulously restored by some of the city’s master artisans. On our way, he points across a narrow street to massive crossbeams propping up buildings. “If one house caves in, others can fall like dominoes,” he says. Radoine himself has led teams to rescue inhabitants from collapsed homes. “Before we began shoring up threatened structures in 1993, four or five people a year were killed,” he says.

When we arrive at the former school, woodworkers are chiseling cedar planks beneath its soaring, ornately carved ceiling. The courtyard walls crawl with thousands of thumb-size green, tan and white tiles—eight-pointed stars, hexagonal figures and miniature chevrons. “The Merenid style was brought by exiles fleeing Spain and represents the apogee of Moroccan art and architecture,” says Radoine. “They had a horror of the void; no surface was left undecorated.”

I make my way out of the medina to the tile-making workshops of Abdelatif Benslimane in the city’s French colonial quarter. Abdelatif and his son Mohammed run a thriving business, with clients from Kuwait to California. Mohammed, a seventh-generation zillij (tile) artisan, divides his time between Fes and New York City. As he shows me the workshop where craftsmen are cutting tiles, he picks up a sand-colored piece formed like an elongated almond, one of some 350 shapes used to create mosaics. “My grandfather would never have worked with a color like this,” he says. “It’s too muted.” The tiles are bound for American clients, who generally prefer less flashy colors. “Even in Morocco, many turn to paler colors and simpler motifs,” he adds. “With smaller new homes, bold designs are overpowering.”

leaving Fés, i drive 300 miles south along a new four-lane highway to verdant, prosperous Settat, then brave the country’s daredevil road warriors on a two-lane artery that winds through hardscrabble market towns and red desert to Marrakech, which an international group of environmental crusaders is trying to revive as the garden oasis of North Africa.

Here Mohamed El Faiz, a leading horticulturist, drives me to the beautiful royal garden of Agdal. Constructed in the 12th century and covering two square miles, it is the oldest garden in the Arab world, at once a prime example of the city’s former glories and urgently in need of restoration. Along the way, he points out scruffy olive groves across from the opulent Hotel La Mamounia. “King Mohammed V planted these groves in the late 1950s as a gift to the people,” he says. “Now, the city is allowing them to die so that real estate developers can build.” A severe drought, coupled with a population explosion, has made gardens more essential than ever. “The city’s population has multiplied from 60,000 in 1910 to more than 900,000 now,” says El Faiz, “and we have less green space.”

At Agdal, El Faiz walks me past date palms and rows of orange and apple trees to a massive elevated reflecting pool beneath a glorious panorama of the high Atlas Mountains and the Jibelet foothills. During the 12th to the 16th centuries, sultans received foreign dignitaries on this spot. “The gardens demonstrated the sultans’ mastery of water,” says El Faiz. “When one had water, one had power.”

Under a brick culvert, a metal gate releases water to the groves by a gravityfed system flowing into small irrigation canals. “The engineers calculated the slope the canals needed to ensure that the precise amount of water reached each tree,” he says. But the system has deteriorated. “If there’s not restoration soon, the walls risk giving way, flooding the garden with millions of gallons of water.”

Back in Marrakech I meet with Gary Martin, an American ethnobotanist who is trying to persuade the government to restore the gardens of the BahiaPalace, which are also dying. The palace is a sprawling 19th-century showcase of masterful tile work and wood carving. Martin and I wind past high-ceilinged ballrooms to emerge into a sun-blasted, abandoned garden that covers more than 12 acres. “It’s a wreck,” I say tactlessly, surveying the withered trees. “It’s definitely devastated now,” Martin cheerfully acknowledges. “But think of the potential! Just look at those daliyas [shady iron-and-wood grape arbors] and that immense bay laurel! If the irrigation system were fixed, this place could be a Garden of Eden in the heart of the medina.”

Plunging back into the old city’s dirt streets, I struggle to keep up as Martin maneuvers through swarms of merchants peddling everything from leather purses to azure pottery. Berber carpets cascade out of shops like multicolored waterfalls. After a depressing detour through the animal souk with its fullgrown eagles trapped in cramped cages, pelts of leopards and other endangered species, we arrive at the Riad Tamsna, a 1920s house that Gary Martin and his wife, Meryanne Loum-Martin, have converted into a tea salon, bookstore and gallery.

The minute I pass through its heavy cedar doors, I feel I’ve entered a different world. A soft light filters onto a courtyard, sparely furnished with couches, handcrafted tables and a large basin of water with floating rose petals. It is soothingly quiet. “There are not many places in the medina where you can rest and collect your thoughts,” Meryanne says, as a waiter in a scarlet fez pours mint tea.

Of Senegalese descent and formerly a lawyer in Paris, Meryanne now designs furniture, and her candelabra, chairs and mirrors complement exhibitions of art, jewelry, textiles and crafts by local designers—as well as works by photographers and painters from France and the United States—in the restored palace. After tea, we go up to a rooftop terrace, where the 230-foot-high Koutoubia minaret dominates the skyline. As a copper sun sets, muezzins sound their overlapping calls to prayer, crackling over scattered loudspeakers like a musical round.

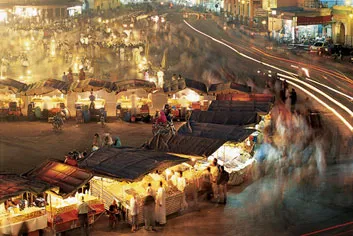

Following evening prayers, it’s showtime at the Place Djemaa el-Fna, the teeming medina crossroads that dates to 12thcentury days when Almohad dynasty sultans cut off rebel leaders’ heads and displayed them on spikes. Forsaking Riad Tamsna, I stumble about the darkening souks, getting thoroughly lost. Eventually I arrive at the three-acre market square that by night becomes a carnival. Dancers costumed in harem pants spin their fez tassels in madcap rhythms as drummers and metal castanet (karkabat) players keep them literally on their toes. Ten feet away, a storyteller lights a kerosene lantern to signal that his monologue, an animated legend that draws a rapt audience, is about to begin. I push past incense sellers and potion vendors to join a crowd gathered around white-robed musicians strumming away at three-stringed goatskin guitars called kanzas. A man playing a single-chord violin, or amzhad, approaches me, fiddles like a Berber Paganini, then doffs his cap for a few dirhams, gladly given. He’s soon replaced by a musician tootling a boogie arabesque on a stubby zmar clarinet favored by cobra charmers. In the midst of the hubbub, alfresco eateries feature chefs serving snails, mussels, spicy merguez sausages, chicken and mountains of fries.

I climb the stairs to the rooftop terrace of the Cafe de France to take my final view of the clusters of performers and star bursts of fire-eaters—all forming and reforming a spectacular human kaleidoscope, filling the void, decorating every space, like the Merenid artisans of old.

While Moroccan cities are dominated by Arab influences, the countryside remains overwhelmingly Berber, particularly in the Atlas Mountains. The Brides’ Fair at Imilchil, which combines marriage ceremonies with harvest celebrations, offers a highspirited opportunity for outsiders to penetrate these normally closed tribal communities. To get there, I take a 220- mile roller-coaster drive north from Marrakech through dense pine forests. Imilchil is a bustling tent city lit by kerosene lanterns. Craggy mountains ring the plain like the sides of an enormous dark bowl.

The next morning, I head to a billowing canvas tent the size of a circus big top where the festivities are just beginning. According to one legend, the Brides’ Fair originated when a pair of star-crossed lovers, a Berber Romeo and Juliet from warring tribes, were forbidden to marry. When they cried so long that their tears formed two nearby lakes, tribal elders gave in. The fair was created to allow men and women from different tribes to meet one another and, if all goes well, to eventually marry. Inside the tent 20 couples, already engaged to be married, are waiting their turn to sign marriage contracts before a panel of notaries. The prospective grooms, wearing crisp, white djellabas, lounge in one corner while the young women, in brightly colored shawls, sit separately in another. Many engaged couples wait until the Brides’ Fair to sign marriage agreements because it’s cheaper. (Normally, a contract costs $50 per couple; at the fair it’s just $12.)

Wandering around the sprawling harvest market, I peer into tents filled with dates, peppers and pumpkins. Teenage girls with arresting green eyes are dressed in dark indigo capes and head scarves tinkling with mirrored sequins. They inspect stands of jewelry and flirt with teenage boys wearing baseball caps emblazoned with Nike and Philadelphia Phillies logos.

Although traditional Berber weddings can last up to a week, such events are closed to outsiders. Brides’ Fair organizers have devised a tourist-friendly alternative. In the nearby village of Agoudal, a 90-minute version is open to all: relatives, friends and tourists. On the way to Agoudal, I pass lush fields of alfalfa and potatoes. Small children hold up green apples for sale, and women bent double by loads of hay tread along on dirt paths.

In the middle of the village square, an announcer narrates each step of the marriage ritual. The comic high point comes when the bride’s messenger goes to the groom’s home to pick up presents on her behalf. As necklaces, fabrics and scarves are piled on her head, the messenger complains that the gifts are paltry things. “More!” she demands, jumping up and down. The audience laughs. The groom adds more finery. “Bring out the good stuff!” At last, head piled with booty, the bearer takes her leave.

Finally, the bride herself, resplendent in a flowing red robe, rides up on a mule, holding a lamb, representing prosperity. A child, symbolizing fertility, rides behind her. As women ululate and men tap out a high-octane tattoo on handheld drums, the bride is carried to the stage to meet the groom. Wearing a red turban and white djellaba, he takes her hand.

After the nuptials, I drive 180 miles southeast to the Merzouga dunes near Erfoud for a taste of the Sahara. What greets me is more than I bargained for: a fierce sirocco (windstorm) pelts hot sand into my mouth, eyes and hair. I quickly postpone my sunset camel ride and go to my tent hotel, where I sip a glass of mint tea and listen for the wind to die down.

An hour before dawn I am rousted out of bed for an appointment with my inner Bedouin. Wrinkling its fleshy snout and casting me a baleful eye, my assigned camel snorts in disapproval. He’s seen my kind before. Deigning to lower himself, the beast sits down with a thump and I climb aboard. “Huphup,” the camel driver calls out. The animal jerks upright, then lumbers forward, setting a stately pace behind the driver. Soon I am bobbing dreamily in sync with the gentle beast’s peculiar stiff-legged walk. The dunes roll away toward Algeria under tufted, gray clouds. Then, for the first time in months, it starts to rain—scattered droplets instantly swallowed up, but rain nonetheless. Ten minutes later, the rain stops as abruptly as it began.

It was Orson Welles who put essaouira, my next destination, 500 miles to the west, on the cultural map. It was at this Atlantic port city, where caravans from Timbuktu once unloaded spices, dates, gold and ivory bound for Europe, that Welles directed and starred in his 1952 film version of Othello. Today the city is a center of Moroccan music and art. The four-day gnaoua (West African trance music) festival in June is one of the few cultural events in the highly stratified country that brings together audiences from all social classes. In the city where Jimi Hendrix once composed psychedelic hits, the festival sparks wildly creative jam sessions among local gnaoua masters, high-energy performers of North African rai music, and experimental jazz pioneers Randy Weston and Archie Shepp.

With its dramatic ramparts, airy, whitewashed medina, blue-shuttered houses and a beach that curves like a scimitar, Essaouira inspires tourists to stay awhile. Parisian Pascal Amel, a founder of the gnaoua festival and parttime resident of the city, and his artist wife, Najia Mehadji, invite me to lunch at the harbor to sample what they claim is the freshest food on the Atlantic coast. Surveying the row of carts groaning with red snapper, sea bream, crabs, sardines and rock lobsters, Amel tells me that small-boat fishermen bring their catch here 300 days a year, failing to appear only when it’s too windy to fish. (The city is also renowned as the windsurfing capital of North Africa.)

Najia vigorously bargains for our lunch with a fishmonger (the tab for the three of us is $13), and we join other diners at a long table. After lunch, I wander past a row of arched enclosures built into the fortress walls, old storage cellars where woodworkers now craft tables, boxes and chairs. High on the ramparts where Welles filmed Othello’s opening scenes, young Moroccans while away the afternoon astride 18thcentury cannon.

In contrast to the chaotic maze of the medinas in Marrakech and Fes, the wide pedestrian walkways of Essaouira’s old town are positively Cartesian. Laid out by French urban planner Theodore Cornut in the 18th century, the boulevards buzz with vendors selling chickens and rabbits.

Through a mutual friend, I make arrangements to meet Mahmoud Gania, one of the legendary masters of gnaoua music. Arriving in the evening at his cinder block house, I am greeted by his wife, Malika, and three irrepressible children. We sit on velvet couches, and Malika translates Mahmoud’s Arabic comments into French. Though Mahmoud’s group of five attracts thousands of fans to concerts in France, Germany, Japan and all over Morocco, traditional gnaoua ceremonies are private, all-night affairs that take place at home among family and friends. The purpose of these recitals is therapy, not entertainment. The idea is to put a person suffering from depression, insomnia or other psychological problems into a trance and exorcise the afflicting spirit; today the ritual is not used to cure serious medical ills.

As Mahmoud and Malika wrap up their description of the ceremony, which involves colored cloths, perfumes, food, drink, incantations, prayers and mesmeric, trance-inducing rhythms, Mahmoud slides onto the floor and begins picking out a hypnotic tune on the goatskin lute called a guimbri. Malika claps in counterpoint, and the drummer from his group joins in, tapping a syncopated beat on a plastic box of a cassette tape. The children are soon clapping and dancing in perfect time. “Hamza is only 10 years old, but he’s learning the guimbri from his father and has already performed with us in Japan,” says Malika, hugging her oldest child.

After a while the group takes a break, and I step outside, alone under the stars, to smell the sea breeze and listen to the distant echo of fishermen dragging their boats across the rocky beach into the surf. Soon, this scraping sound mingles with the faint plucking of the guimbri as the music resumes inside. Caught up in the Moroccan need to entertain and be entertained, they’ve started without me. Escaping the guimbri, like sleeping through Imilchil’s Berber festival, is out of the question. I inhale the night air. Refreshed, I slip back inside, ready for more.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.