How an Earthquake Turned This New Zealand Town into the Art Deco Capital of the World

Napier turned its tragic past into an architectural wonder

For Murray Houston, February 3, 1931 started out like any ordinary day. The now 91-year-old New Zealander was sitting inside the small wooden schoolhouse he attended in the coastal town of Napier, when the walls began to shake violently, sending textbooks flying and desks crashing to the floor. Only six years old at the time, Houston did the first thing that came to mind—he ran.

“I remember all of us students running from the school like bees out of the hive,” he tells Smithsonian.com. “Children were hanging onto the fences. Otherwise they would have fallen over since the ground wouldn’t stop shaking.”

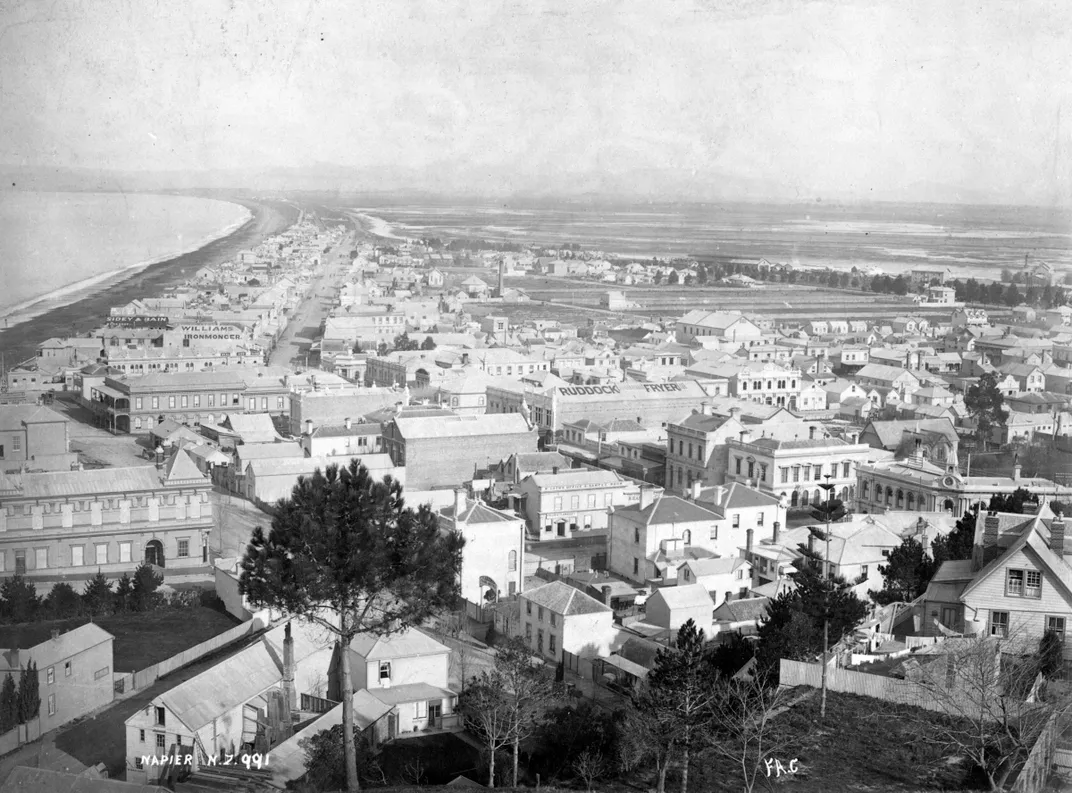

The Hawke’s Bay earthquake only lasted two-and-a-half minutes, but it became infamous as the deadliest natural disaster in New Zealand, claiming at least 250 lives and measuring 7.8 on the Richter scale. All but a few of Napier’s buildings were completely destroyed by the earthquake and the fires that followed.

Today, the ramifications of the tragedy are still part of the fabric of this town of 61,500—but not in the ways one might expect. Visitors can see echoes of the earthquake in both the pastel-colored Art Deco buildings that line the city’s streets and in the town’s increased footprint—the earthquake pushed the seabed up three to six feet, offering ample space to rebuild. And rebuild Napier did.

Napier came back from the earthquake with a clean slate and fresh land to build on. One hundred and eleven new buildings were constructed in the downtown area between 1931 and 1933. The vast majority took their cues from Art Deco, the era’s cutting-edge architectural trend. The architectural style is known for its linear structure and touches of intricate ornamentation in the form of geometric motifs like chevrons and zigzags. It was also relatively inexpensive thanks to its basic, boxy designs—a bonus considering that the earthquake struck during the middle of the Great Depression, the worst economic downturn in history.

“Only one out of every 100 residents had insurance, so there wasn’t a lot of money to play with,” Sally Jackson, general manager of the Art Deco Trust, tells Smithsonian.com. “Many people had to take out second mortgages to rebuild their homes.” Spanish Mission, Prairie Style and Stripped Classical architectural styles also made their way to Napier during the reconstruction, but Art Deco reigned supreme.

As they reimagined their town as an Art Deco showcase, families lived in canvas tents supplied by the government on what was left of their properties or in “tent towns” set up in local parks. Napier architects like J. A. Louis Hay, who was largely influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright, safeguarded the new structures with the latest engineering techniques, building with reinforced concrete and opting for buildings that stood two stories or less to guard against future earthquakes. (New Zealand is prone to earthquakes thanks to several fault lines that run the length of the country.)

At the time, Napier’s residents just wanted to move on with their lives. Little did the townspeople realize that their reconstruction efforts would result in the highest concentration of Art Deco buildings on Earth, earning it the title of Art Deco Capital of the World.

Today, Art Deco still dominates Napier’s skyline. (Even the local McDonald’s is housed inside an Art Deco building.) To help protect, preserve and promote Napier’s rich architectural heritage, the city formed an Art Deco Trust in 1985. For the past 18 years, the trust has held an annual Tremains Art Deco Festival. The celebration, which draws crowds in the tens of thousands, includes more than 125 events like walking tours, vintage car shows, dances, a soapbox derby and jazz concerts. This year’s event began February 17 and runs through 21.

“Nowhere else in the world will you find as immense a collection of Art Deco architecture in such a small space, all next door to each other,” says Jackson. “Not even South Beach Miami.”

Maxine Anderson has been conducting architectural walking tours for the trust for more than a decade. She wasn't alive when the earthquake struck, but as a fourth-generation Napier resident, the natural disaster looms large in her family history in stories from her mother and grandmother. At the time, she explains, many families were separated—many women and children were sent to live elsewhere due to the fear of earthquake aftershocks.

“My mother didn’t know for several months if my grandmother was still alive,” Anderson tells Smithsonian.com. “To this day, my mother still has all of the furniture in her home bolted to the walls.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/17/f3/17f3641a-989c-46a3-8546-57f5ee654fb7/42-22998403.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/27/b72798ff-94fc-4846-babd-a7879528dff2/42-43650395.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/58/8a/588a04f2-58f1-4801-84de-9d15e23a9a28/42-53679611.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/52/d752a3b5-9f36-4e32-ae7c-ac0a50810ff2/42-65681323.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/fe/0efee95e-49ce-4ce1-b10e-ae353c9af9a8/4675320546_eda9686d43_b.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/23/c323da89-2074-4612-97a7-31abc0df4b73/24286385759_aef964b01e_k.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/de/1cde725d-73aa-484a-9106-f0813a2ac022/24028459363_1048cf1965_b.jpg)