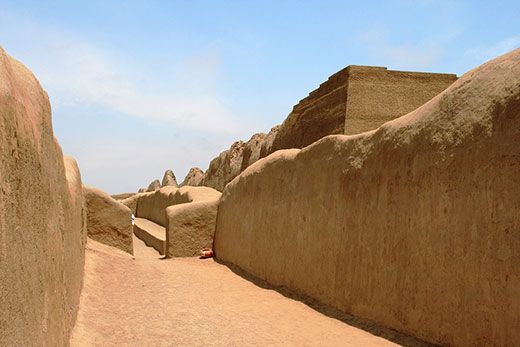

Endangered Site: Chan Chan, Peru

About 600 years ago, this city on the Pacific coast was the largest city in the Americas

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Chan-Chan-Peru-631.jpg)

During its heyday, about 600 years ago, Chan Chan, in northern Peru, was the largest city in the Americas and the largest adobe city on earth. Ten thousand structures, some with walls 30 feet high, were woven amid a maze of passageways and streets. Palaces and temples were decorated with elaborate friezes, some of which were hundreds of feet long. Chan Chan was fabulously wealthy, although it perennially lacked one precious resource: water. Today, however, Chan Chan is threatened by too much water, as torrential rains gradually wash away the nine-square-mile ancient city.

Located near the Pacific coast city of Trujillo, Chan Chan was the capital of the Chimú civilization, which lasted from A.D. 850 to around 1470. The adobe metropolis was the seat of power for an empire that stretched 600 miles from just south of Ecuador down to central Peru. By the 15th century, as many as 60,000 people lived in Chan Chan—mostly workers who served an all-powerful monarch, and privileged classes of highly skilled craftsmen and priests. The Chimú followed a strict hierarchy based on a belief that all men were not created equal. According to Chimú myth, the sun populated the world by creating three eggs: gold for the ruling elite, silver for their wives and copper for everybody else.

The city was established in one of the world's bleakest coastal deserts, where the average annual rainfall was less than a tenth of an inch. Still, Chan Chan's fields and gardens flourished, thanks to a sophisticated network of irrigation canals and wells. When a drought, coupled with movements in the earth's crust, apparently caused the underground water table to drop sometime around the year 1000, Chimú rulers devised a bold plan to divert water through a canal from the Chicama River 50 miles to the north.

The Chimú civilization was the "first true engineering society in the New World," says hydraulic engineer Charles Ortloff, who is based in the anthropology department of the University of Chicago. He points out that Chimú engineering methods were unknown in Europe and North America until the late 19th century. Although the Chimú had no written language for recording measurements or drafting detailed blueprints, they were somehow able to carefully survey and build their massive canal through difficult foothill terrain between two valleys. Ortloff believes the canal builders must have been thwarted by the shifting earth. Around 1300, they apparently gave up on the project altogether.

While erratic water supplies created myriad challenges for agriculture, the Chimú could always count on the bounty of the sea. The Humboldt Current off Peru pushes nutrient-rich water up to the ocean's surface and gives rise to one of the world's richest marine biomasses, says Joanne Pillsbury, director of pre-Columbian studies at Washington, D.C.'s Dumbarton Oaks, a research institute of Harvard University. "The Chimú saw food as the tangible love their gods gave them," Ortloff says. Indeed, the most common images on Chan Chan's friezes are a cornucopia of fish, crustaceans and mollusks, with flocks of seabirds soaring overhead.

Chan Chan's days of glory came to an end around 1470, when the Inca conquered the city, broke up the Chimú Empire and brought many of Chan Chan's craftsmen to their own capital, Cuzco, 600 miles to the southeast. By the time Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro arrived around 1532, the city had been largely abandoned, though reports from the expedition described walls and other architectural features adorned with precious metals. (One of the conqueror's kinsmen, Pedro Pizarro, found a doorway covered in silver that might well have been worth more than $2 million today.) Chan Chan was pillaged as the Spaniards formed mining companies to extract every trace of gold and silver from the city.

Chan Chan was left to the mercy of the weather. "The Chimú were a highly organized civilization" and any water damage to the adobe-brick structures of Chan Chan "could be repaired immediately," says Claudia Riess, a German native who now works as a guide to archaeological sites in northern Peru. Most of the damage to Chan Chan during the Chimú reign was caused by El Niño storms, which occurred every 25 to 50 years.

Now they occur more frequently. Riess believes that climate change is a primary cause of the increasing rainfall—and she's not alone. A 2007 report published by Unesco describes the erosion of Chan Chan as "rapid and seemingly unstoppable" and concludes "global warming is likely to lead to greater extremes of drying and heavy rainfall." Peru's National Institute of Culture is supporting efforts to preserve the site. Tentlike protective structures are being erected in various parts of the city. Some friezes are being hardened with a solution of distilled water and cactus juice, while others have been photographed, then covered to protect them. Panels with pictures of the friezes allow visitors to see what the covered artwork looks like.

Riess believes the best solution for Chan Chan would be a roof that stretches over the entire area and a fence to surround the city. But she acknowledges that both are impractical, given the ancient capital's sheer size. Meanwhile, the rains continue, and Chan Chan slowly dissolves from brick into mud.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.