Endangered Site: Chinguetti, Mauritania

The rapidly expanding Sahara Desert threatens a medieval trading center that also carries importance for Sunni Muslims

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Chinguetti-Mauritania-631.jpg)

The Sahara is expanding southward at a rate of 30 miles per year—and part of the desert's recently acquired territory is a 260-acre patch of land in north-central Mauritania, home to the village of Chinguetti, once a vibrant trading and religious center. Sand piles up in the narrow paths between decrepit buildings, in the courtyards of abandoned homes and near the mosque that has attracted Sunni pilgrims since the 13th century. After a visit in 1996, writer and photographer Kit Constable Maxwell predicted that Chinguetti would be buried without a trace within generations. "Like so many desert towns through history, it is a casualty of time and the changing face of mankind's cultural evolution," he wrote.

Coincidentally, that same year the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) designated the town a World Heritage Site, which spotlighted its rich past and precarious future. Yet, Chinguetti's fortunes have not improved. A decade later, a UNESCO report noted that global climate change is delivering a one-two punch: seasonal flash flooding, which causes erosion, and increased desertification, which leads to more frequent sandstorms and further erosion. Workers in Chinguetti have the Sisyphean task of wetting down the sand to prevent it from being blown about.

Today's Chinguetti is a shadow of the prosperous metropolis it once was. Between the 13th and 17th centuries, Sunni pilgrims en route to Mecca gathered here annually to trade, gossip, and say their prayers in the spare, mostly unadorned mosque, built from unmortared stone. A slender, square-based minaret is capped by five clay ostrich egg finials; four demarcate the cardinal directions and the fifth, in the center, when seen from the West, defines the axis toward Mecca.

Desert caravans were the source of Chinguetti's economic prosperity, with as many as 30,000 camels gathering there at the same time. The animals, which took refreshment at the oasis retreat, carried wool, barley, dates and millet to the south and returned with ivory, ostrich feathers, gold and slaves.

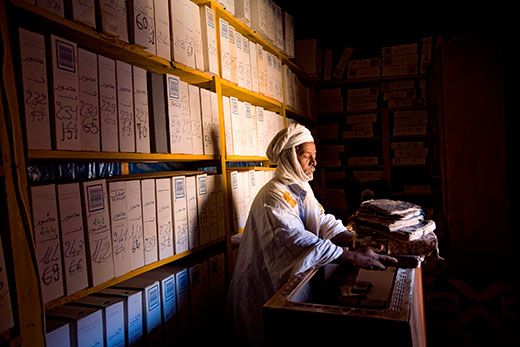

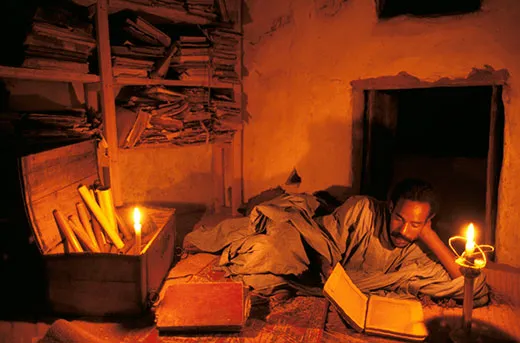

Once home to 20,000 people, Chinguetti now has only a few thousand residents, who rely mostly on tourism for their livelihood. Isolated and hard to reach (65 miles from Atar, by Land Rover; camels not recommended), it is nonetheless the most visited tourist site in the country; its mosque is widely considered a symbol of Mauritania. Non-Muslim visitors are prohibited from entering the mosque, but they can view the priceless Koranic and scientific texts in the old quarter's libraries and experience traditional nomadic hospitality in simple surroundings.

Chinguetti is one of the four ksours, or medieval trading centers, overseen by Mauritania's National Foundation for the Preservation of Ancient Towns (the others are Ouadane, Tichitt and Oualata). The United Nations World Heritage Committee has approved extensive plans for the rehabilitation and restoration of all four ksours and has encouraged Mauritania to submit an international assistance request for the project.

But such preservation efforts won't forestall the inevitable, as the Sahara continues to creep southward. Desertification has been an ongoing process in Mauritania for centuries. Neolithic cave paintings found at the Amogjar Pass, located between Chinguetti and Atar, depict a lush grassland teeming with giraffes and antelope. Today, that landscape is barren. May Cassar, professor of sustainable heritage at the University College London and one of the authors of the 2006 UNESCO report on climate change, says that solving the problem of desertification requires a sustained effort using advanced technologies.

Among the most promising technologies under development include methods for purifying and recycling wastewater for irrigation; breeding or genetically modifying plants that could survive in arid, nutrient-starved soil; and using remote sensing satellites to preemptively identify land areas at risk from desertification. Thus far, low-tech efforts elsewhere in the world have been a failure. along the Mongolian border, Chinese environmental authorities sought to reclaim land overrun by the Gobi Desert by planting trees, dropping seeds from planes and even covering the ground with massive straw mats. All to no avail.

"We as cultural heritage professionals are faced with a growing dilemma that we may have to accept loss, that not everything can be saved." says Cassar. Or, to quote an old saying: "A desert is a place without expectation."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.