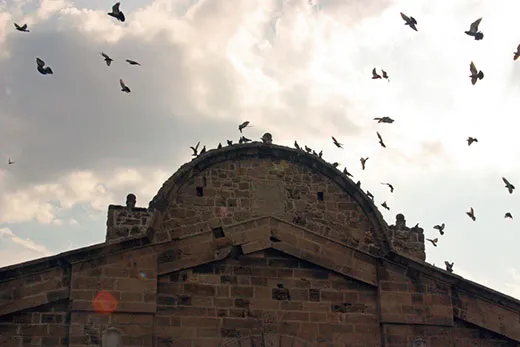

Endangered Site: Famagusta Walled City, Cyprus

Once located in the midst of high-volume shipping lanes, a forgotten city with multiple European influences could be lost forever without an intervention

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Famagusta-Walled-City-631.jpg)

"All ships and all wares," a 14th-century German traveler wrote, "must needs come first to Famagusta." The port city on the northeastern coast of Cyprus was once on a bustling shipping lane, carrying merchants from Europe and the Near East and armies of Christian knights and Ottoman Turks. Famagusta rose to prominence between the 12th and 15th centuries, most notably as the city where the Crusader kings of Jerusalem were crowned.

Now ancient Famagusta, tucked into a modern city of 35,000 people, also called Famagusta, is largely forgotten, except, perhaps, as the setting for Shakespeare's Othello. Some 200 buildings—reflecting Byzantine, French Gothic and Italian Renaissance architectural styles—are in a state of disrepair. Weeds and wildflowers press against sandstone walls eroded by rain and earthquakes. Agencies such as UNESCO are unable to send either funds or conservationists due to the economic and social embargo the international community imposed on northern Cyprus after it was forcibly annexed by Turkey in 1974. "The city has always been fought over and so its current condition is simply another page in its turbulent history," says Michael Walsh, associate professor of art history at Famagusta's Eastern Mediterranean University. "It is shrouded in a melancholy that is unbefitting it, awaiting better days reminiscent of those it experienced 600 years ago."

Built in the 10th century on the site of Arsinoe—an ancient city founded by Egyptian ruler Ptolemy II Philadelphus in the 3rd century B.C.—Famagusta was a Mediterranean backwater until Christian Crusaders came to the region. Richard the Lionheart, en route to his third Crusade, captured Cyprus and later sold it to the Knights Templar, who then sold it to French knight Guy de Lusignan in 1192, who was looking for new real estate after he had been deposed as the king of Jerusalem by the Muslim leader Saladin in 1187.

Famagusta flourished during the next three hundred years, its shops bulging with goods as merchants bartered in Greek, Arabic, Italian, French and Hebrew. By the middle of the 14th-century, Famagusta's citizens had built some 365 churches (one for every day of the year, it was said). Two miles of walls, as well as a moat, protected the city. "There are very few medieval walled cities in Europe that compare," says Allan Langdale, an art history professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz who, in 2007, produced a documentary about the city. "Every 20 or 30 paces you come across a new piece of architecture….You get a real sense of a real medieval, moated city."

By the late 15th century, Famagusta had fallen under the control of Venice and its merchant princes, who took over Cyprus to shore up their economic and political interests in the Eastern Mediterranean. The Venetians fortified the city's walls, making them 50 feet thick in some places. "This is a very fair stronghold," a visiting English merchant wrote in 1553, "the strongest and greatest in the land." But it wasn't enough.

In 1570, Ottoman Turks sent cannon balls ripping through the walls in a siege that lasted for nearly a year. Outnumbered and starving, the Venetians surrendered in 1571. The Ottomans took over Cyprus and closed Famagusta to Christians. They built fountains throughout the city to modernize the water supply, and they converted most of the churches to mosques. A minaret was placed above the gothic buttresses of the former Cathedral of St. Nicholas, where Jerusalem's kings had once been coronated. Churches that weren't converted—as well as other buildings damaged by the siege—were left to ruin. By the 19th century only a handful of residents remained, most living in shacks attached to deteriorating churches. In 1878, when the British occupied Cyprus, Scottish photographer John Thomson called Famagusta "a city of the dead."

Cyprus finally gained independence in 1960, only to be invaded by Turkey and forcibly partitioned fourteen years later. Ancient Famagusta moldered, and what remains is fast disappearing. The city walls still bear the pockmarks from Ottoman cannon balls, which litter the grounds below. Those domes, arches and ribbed vaults not already gone are on the verge of collapse. "When the next seismic activity occurs here, the walls may not survive," says Walsh. Church frescos, most notably on the exposed walls of St. George of the Greeks, are in perilous condition, having been washed by rain, disturbed by earthquakes and bleached by the sun. "Nothing is more at risk than the paintings," says Walsh.

As the elements threaten the buildings and fortifications, so does a recent real estate boom. Speculators are putting up housing in and around modern Famagusta to accommodate the city's increasing population. "Who is going to give a second glance at the heritage of the city and environs?" asked Walsh in a recent report for the International Council on Monuments and Sites, a Paris-based organization devoted to the preservation of the world's cultural heritage.

Those who might give Famagusta a second glance are hampered by Cyprus's division into a Turkish-Muslim north and Greek-Orthodox south. The south is recognized internationally and, in 2004, was inducted into the European Union. The north—known alternately as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus or the "Occupied Territories" of the Republic of Cyprus—is not recognized internationally. Located just north of the dividing line, Famagusta is accessible to visitors only through southern ports. The city has both a Turkish mayor and a Greek mayor-in-absentia, who represents Greek Cypriots who fled in 1974 and have not been permitted to return. Some suggest that efforts to save Famagusta should await Cyprus's reunification, but Walsh believes time is running out.

In April 2008, under the guidance of Europa Nostra, a pan-European federation for cultural heritage, the Greek and Turkish mayors of the city met in Paris. They agreed to put aside their political differences and support efforts to preserve Famagusta. Europa Nostra hopes that their shared interest in conservation will create an opening for international agencies to donate money, without giving rise to legal or political disputes.

"A city of such colossal importance would normally receive millions of dollars of aid annually and could rely on the advice of art and architecture experts from all over the world," says Walsh. "This is what Famagusta needs, and the recent meeting shows that Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots agree fully with this." It might be the only thing they agree upon.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.