Endangered Site: Xumishan Grottoes, China

This collection of ancient Buddhist cave temples date back to the fifth and tenth centuries, A.D.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Xumishan-Grottoes-China-631.jpg)

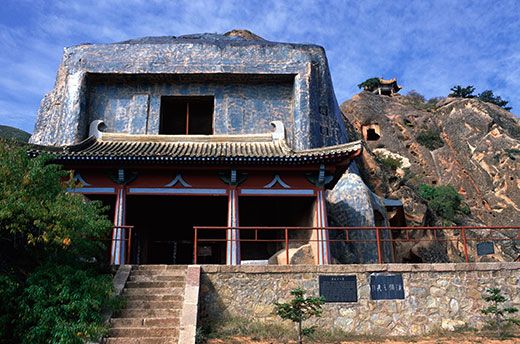

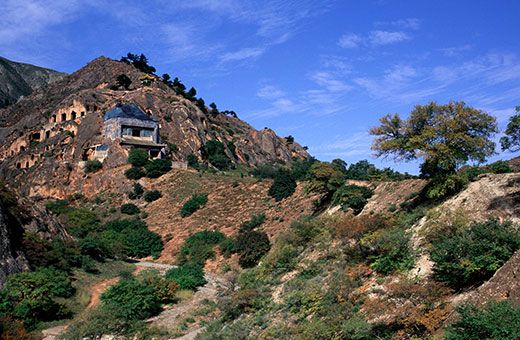

Throughout history, human settlement has been driven by three basic tenets: location, location, location. And the Xumishan grottoes—a collection of ancient Buddhist cave temples constructed between the fifth and tenth centuries A.D.—owe their existence to this axiom. Located in China's Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Xumishan (pronounced "SHU-me-shan") capitalized on its proximity to the Silk Road, the crucial trade artery between East and West that was a thoroughfare not only for goods but also for culture and religious beliefs. Along this route the teachings of Buddha traveled from India to China, and with those teachings came the cave temple tradition.

Hewed out of red sandstone cliffs—most likely by artisans and monks, funded by local officials and aristocrats—the Xumishan grottoes break into eight clusters that scatter for more than a mile over starkly beautiful, arid terrain. The construction of the approximately 130 grottoes spans five dynastic eras, from the Northern Wei (A.D. 386-534) to the Tang (A.D. 618-906). Although there are more extensive cave temples in China, Xumishan "is kind of a new pearl that's very little known," says Paola Demattè, an associate professor of Chinese art and archaeology at the Rhode Island School of Design. Historical records offer scant details about the site, but clues can be found among inscriptions on cave walls—such as the devotional "Lu Zijing" from A.D. 848, in which "a Buddha's disciple wholeheartedly attends to the Buddha"—and steles (stone slabs), particularly three from the 15th century that recount a sporadic history of the caves.

One of the steles contains the first written reference to the name "Xumishan"—a Chinese-language variation of "Mount Sumeru," the Sanskrit term for Buddhism's cosmic mountain at the center of the universe. Before the grottoes were carved, the site was known as Fengyishan. Nobody knows for sure when and why the mountain was renamed. Some have suggested that it was basically an exercise in rebranding, to make the site more compelling to pilgrims. Others, such as Harvard's Eugene Wang, an expert on Chinese Buddhist art, see no special significance in the name change, since Xumishan was a widely used Buddhist term by the time it became attached to the site.

Nearly half of the grottoes are bare and may have served as living quarters for monks. Wall paintings and statues decorate the rest, where influences from India and Central Asia are evident. Cave 33's square layout, with its partition wall punctuated by three portals and pillars that reach to the ceiling, resembles a temple style that emerged in India during the second or first century B.C. Central Asian influence can be seen in

Cave 51's two-level, four-chambered, square floor plan and in its central pillar, a Chinese variation on the dome-shaped stupa that symbolizes the Buddha's burial mound.

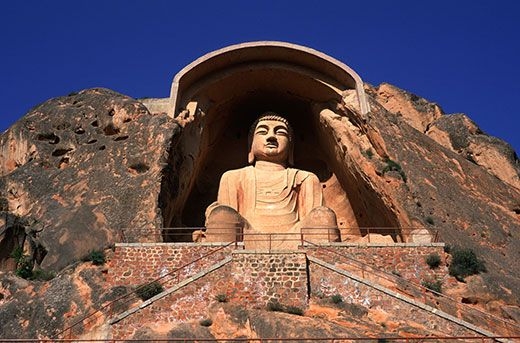

Overlooking the landscape is a 65-foot Tang dynasty Buddha, seated in a kingly posture. The colossal statue represents Maitreya, the Buddha of the future. The concept of Maitreya is somewhat similar to Christian, Jewish and Persian Messianic traditions, says Demattè: "Once the historic Buddha passed away, there was this great expectation that another Buddha would come." Multiple depictions of Maitreya can be found throughout Xumishan's grottoes.

Designated a nationally protected cultural relics site by China's State Council in 1982, Xumishan's grottoes face severe threats from wind and sand erosion, unstable rock beds and earthquakes. According to Demattè, only about 10 percent of the caves are in good condition. Some are so damaged they hardly seem like caves at all; others are blackened with soot from previous occupation or have suffered from vandalism or centuries' worth of droppings from birds and other pests.

After archaeologists from Beijing University surveyed the caves in 1982, some restoration efforts, however misguided, were made. Cement was used to patch parts of the colossal Buddha and to erect an overhang above the sculpture, which was exposed after a landslide in the 1970s. (Cement is ill advised for stabilizing sandstone, since it is a much harder substance than sandstone and contains potentially damaging soluble salts.) To prevent vandalism, grated gates that allow tourists to peer through them have been installed at cave entrances. China's cultural heritage advisers have also started training the local authorities about proper conservation practices.

Even with these measures, it's hard to say what the future holds for Xumishan. Increased scholarly investigation of the site may help. "We need to carefully document every inch," Wang says, "to preserve the grottoes digitally because there's no way to physically preserve them forever." It's a sentiment that resonates with one of the Buddha's main teachings—everything changes.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.