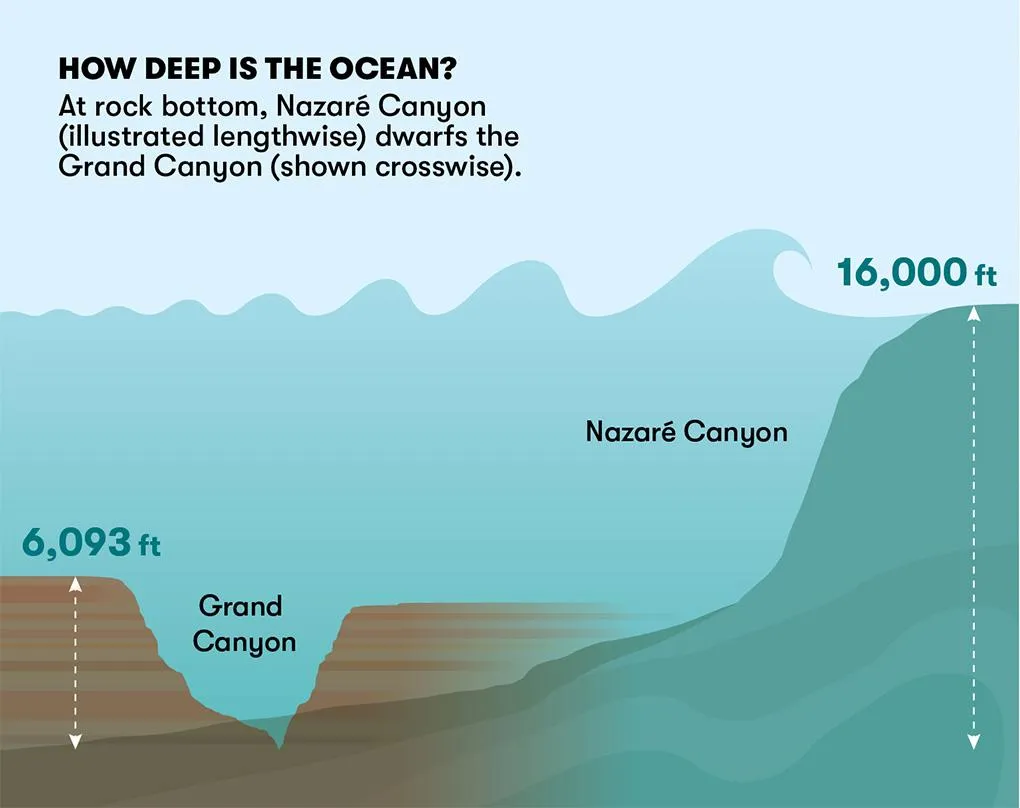

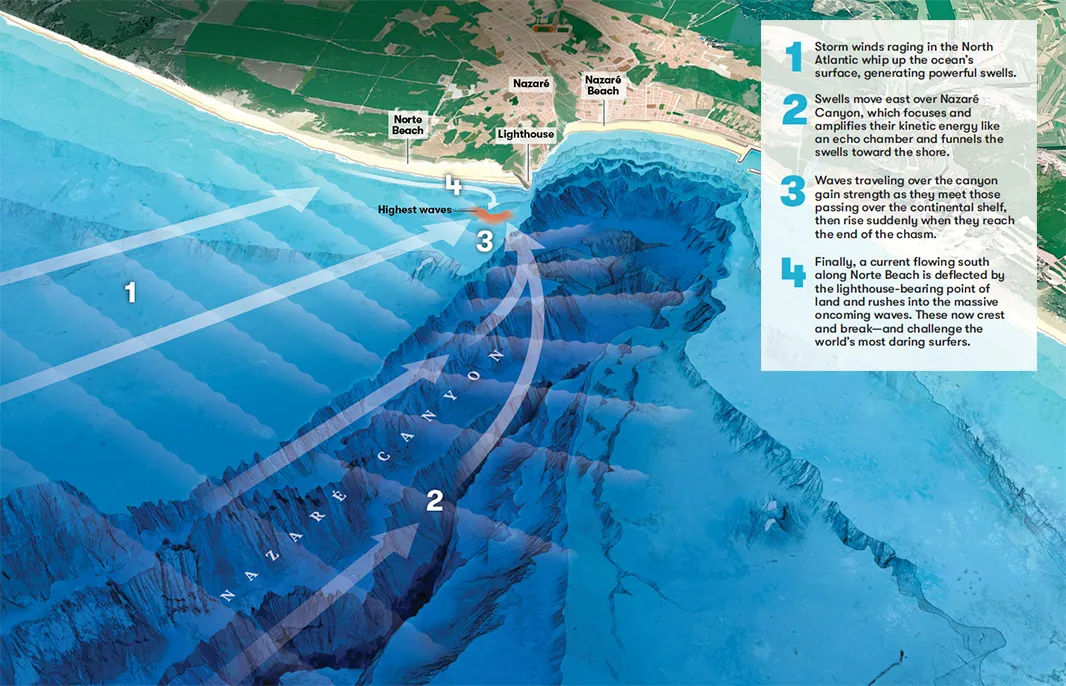

Not all of nature’s wonders are easily visible. Take the canyon under the sea off Nazaré in Portugal. This immense gash is more than three miles deep, and extends from near the shore, widening west for about 140 miles, half the length of the Grand Canyon but almost three times deeper. Its effect on the turbulent ocean is monumental: A swell from far offshore rolls over this submarine canyon, and the shelves and cliffs that line the narrowing funnel squeeze and speed the swell, until a shallow obstructing ledge nearer the shore lifts it, creating a monster wave.

It is perhaps the biggest wave in the world, the widest, the thickest and the highest, often in winter topping 100 feet—the height of a nine-story building. Throughout history the wave killed so many people, that Nazaré—named for Nazareth—was known as a place of death.

Vasco da Gama stopped here in 1497, before leaving for India, but that was in the summer, before the Nazaré wave began to mount. Many fishermen have set sail from Nazaré—it has been a fishing port for 400 years. But after a long successful voyage a great number of those fishing boats have met the wave and been dashed against the rocks on Nazaré’s promontory. For this reason Nazaré has for centuries been a town of widows, treading its narrow streets in black dresses and shawls, casting their eyes resentfully at the terrifying wave that destroyed their loved ones.

Because of the danger and the deaths, and the decline in the fishing industry, Nazaré endured hard times and became one of the many poor Portuguese towns that supplied the world with migrants, looking for better lives in the Americas and Portuguese colonies in Africa and the Far East. It seemed to many in Nazaré that there was no hope for the place, seemingly cursed with an evil wave that appeared like an avenging giant each winter and was catastrophic for the town.

But a man in Nazaré named Dino Casimiro had an idea. He had heard of the success of an expert surfer in Hawaii, Garrett McNamara, who had ridden big waves all over the world—in Tahiti, Alaska, Japan and even the bulky but solitary wave that at times rises to 80 feet and breaks in the middle of the ocean on a submerged seamount 100 miles off San Diego, on the Cortes Bank.

Dino thought McNamara might be interested in visiting Nazaré and scoping out the wave, and perhaps might dare to ride it. And if he rode it and did not die, Nazaré might find itself on the map, and with a tourist industry; might even enjoy a degree of prosperity, granting it a reprieve from its destitution and its almost certain fate as a failed fishing town.

This was in 2005. Dino found an address for Garrett and sent an email describing the huge wave and inviting him to Nazaré.

And nothing happened.

**********

The reason Dino got no reply was that he had sent the message to a man whose existence away from the ocean was like riding one misshapen wave after another, the junk waves of a careless life, and a collapsing marriage, frittering money away, looking for sponsors, but also—somehow—still riding big waves and soaring through tubes, looking for bigger ones, and winning prizes. In fact, after receiving Dino’s email and mislaying it, Garrett was engaged on a worldwide journey, some of which he recorded in his uncompleted film Waterman, his dream of fulfillment, his search for a 100-foot wave.

His marriage ended, the chaos around him subsided, and Garrett fell in love again. Nicole, the new woman in his life, became the steadying force he had lacked since childhood, and one day in 2010, Nicole found Dino’s plaintive email and invitation and said, “What’s this all about?”

Within months, Garrett and Nicole were standing on the high cliff near the lighthouse at Nazaré, awestruck into silence by the sight of the incoming wave—and Garrett finally said that it was bigger than anything he had ever seen.

He had seen a great deal in his life. The kindest way to describe his upbringing is improvisational: His mother on her frenzied journey as a searcher spent years falling by the wayside, hoping for answers to life’s questions. She fled with the infant Garrett from Pittsfield, Massachusetts, to Berkeley, California, where her marriage ended; she was just in time to hop aboard any vehicle—real or imaginary, or dabble in substances, legal or illegal, to help her in her quest. What her quest was, in Garrett’s telling, and in the pages of his 2016 memoir, Hound of the Sea, was never quite clear, but it seemed random and risky, her following one kook after another, settling for periods of time in communes and cults. Her searching extended as far as Central America, where, his mother later told him, 5-year-old Garrett witnessed his mother being kicked in the head by her enraged partner until she was bloody and unconscious. Her abuser was Luis, whom Garrett’s mother met on a road trip to Honduras. Every so often his mother abandoned Garrett, leaving him with strangers. In Guatemala a peasant farmer, recognizing the neglect, begged to adopt him. Garrett was willing and might have grown up tending a maize field, raising chickens and living on tamales. But his mother brought him back on the road.

After that, another fit of inspiration, another piquant memory. “My mother found God,” Garrett says. “That is, she joined a strange Christian cult, the Christ Family. They were dominated by a guy who called himself ‘Jesus Christ Lightning Amen’ and they were committed to getting rid of all material things—no killing, no money, no possessions, no meat.”

Garrett’s mother made a bonfire, in one sudden auto-da-fé in Berkeley, and tossed in all the combustible money they had, and all their clothes, their shoes, their beat-up appliances, until they were left with—what? Some bedsheets. And these bedsheets became their “robes”—one sheet wrapped like a toga, the other in a bundle over the shoulder.

Hound of the Sea: Wild Man. Wild Waves. Wild Wisdom.

In this thrilling and candid memoir, world record-holding and controversial Big Wave surfer Garrett McNamara chronicles his emotional quest to ride the most formidable waves on earth.

“And there we were, my mother and my brother, Liam, and me, walking up Emerson Street in Berkeley, wearing these white robes—a rope for a belt—and we were barefoot. I ducked into the alleys so that none of my school friends would see me. I tried to hide. But they saw me in my robes. One of the worst humiliations of my life.”

He was 7. They slept rough and begged for food. “We ate out of trash cans and dumpsters from Mount Shasta to Berkeley, for six months or more.”

When they failed to find Lightning Amen or salvation, Garrett’s mother left the boy in Berkeley with his birth father. Garrett became a committed skateboarder and stoner—one of those urchins you see in malls and playgrounds and back alleys all over America, doing wheelies and howling, the Lords of Dogtown set, celebrating being nature’s outcasts, grinding along the edge of a low wall, sometimes crashing—“slamming”—into the concrete and breaking bones—or “bombing a hill,” the nearest thing in skateboarding to surfing a big wave.

After a few years, Garrett’s mother reappeared out of the blue and reclaimed him. She had a new partner, Darryl, a small and younger black lounge singer who dressed like a dandy and went along with the idea that their future—nebulous at best—might lie in Hawaii. If the white robes of the Christ Family had been a humiliation, the spiffy costumes that his mother and Darryl designed for them all to wear on their migration to Hawaii were even more outrageous: orange velvet jackets with gold trim and vests, orange bell-bottoms, shiny footwear and slicked hair, as Garrett remembers, cringing, “something out of the Jackson 5.”

The decade-long journey that included neglect, abuse, drugs, near-madness, alienation, dislocation, fanatical faith, escapes through jungles and deserts, and some high adventure now took root on Oahu’s North Shore in Hawaii. But Garrett, committed to compassion, in his ambition to being “a soul surfer,” is forgiving.

“Yes, it was bad. But I want to give my mother credit for bringing me to Hawaii, and liberating me—against the odds,” he says. “I could have copped out and said, ‘That’s who I am.’ But I chose not to become a victim. I just kept going forward, looking for happiness. I was very ambitious to find security, because there was never anything secure in my life.”

The tiny apartment in a decaying apartment house in Waialua did not offer security; and for Garrett and Liam, living in relative poverty, and haole—white—a racial minority at Waialua High School, it meant battling the local bullies on the first day of class. Nor did the ocean offer much relief.

“I was terrified of big waves, and was afraid of any wave over six feet.”

He was then in his early teens, capable of riding the small surf because of his skateboard prowess. Turning 16, this hapless child had a bit of luck. A visiting Peruvian surfer, Gustavo Labarthe, seeing Garrett’s style of wave riding, loaned him a special board—and in Garrett’s telling it is like King Arthur possessing the sword Excalibur.

“It was a Sunset Point, Pat Rawson board,” Garrett says. “Rawson lived at Sunset Point. It was the perfect board for that break. And Gustavo’s advice was perfect, too—where to go, where to sit in the lineup, how to catch the wave. The board worked magic—I caught every wave—20-foot faces, my first big day on the water.”

He was so happy he grew careless riding the board into the shore-break at the end of the day. The nose of the board rammed the sand and the board buckled in the middle.

“Punky, what did you do!” Gustavo cried out, using the nickname he’d given Garrett.

Garrett atoned for the broken board by washing Gustavo’s car.

But that day was the beginning of the big-wave quest. Local board shapers, the Willis brothers, “sponsored” him—gave him a board. A local promoter entered Garrett in the Triple Crown—Hawaii’s legendary surfing competition trifecta— and Garrett won prize money. And then from the 20-footers of Sunset, he was riding the 30-footers of Banzai Pipeline and finally the biggest waves in Hawaii, in Waimea Bay—40- and the rare 50-footers, which close out the bay in an immense boiling of white froth. Garrett, once the urchin, was on his way to becoming a pro-surfer champion.

There were setbacks. He was badly injured on a wave in 1990, “pitched from the top of the boil and slingshotted into the air, landing on the tail of his board” is how he puts it. He fractured ribs and twisted his spine, and he thought it was possible that he might never surf again. But within the year he was catching waves and back in business.

In 2002 he won the Tow Surfing World Cup in Maui. He was praised for his daring, often shown in a balletic move on the covers of surf magazines. He surfed throughout the Pacific, and in Mexico and Japan, where, with high-profile sponsorships, he was considered a rock star.

“I wanted to get in the barrel,” he says, speaking with joy of the cavernous hollow that forms and holds in a breaking, rolling wave. “Being in the barrel is the most amazing feeling. Time stands still. You can feel your heart beat.”

And sometimes you drown. So it was Garrett’s mastery of the biggest waves, and his survival—his grace—in his long rides in the barrel that placed him in the pantheon of great surfers and made him a pioneer in the sport.

But the biggest waves in the world are unforgiving, and do not always allow a surfer to paddle into them on a board. Even the best surfers can be rebuffed by these waves, pushed back to the shore, where they attempt to paddle out again, often not making it to the point on the break where they can catch a ride. In the early 1990s the Hawaii surfer Laird Hamilton devised a method for catching the biggest waves, by being towed past the buffeting of the surf zone, holding a rope attached to a motorized inflatable, and later a jet ski, which was able to position them on a wave. This innovation—loudly disdained by some surfers—made it possible to ride giants.

Garrett became a tow-in enthusiast and sought the waves at Cortes Bank and the monster break at Teahupo’o in Tahiti and the equally formidable wave at Jaws in Maui. He was growing older, too, and strengthening, becoming braver. This is interesting: an older surfer is sometimes at an advantage on a big wave.

“It doesn’t require the agility and gymnastics of small-wave surfing,” says the writer and former pro surfer Jamie Brisick, a friend of mine. “It more favors experience and ocean knowledge, hence you get an older, wiser bunch of athletes who are generally a lot more fun to talk to.”

This was why, after all this time, when Garrett finally arrived at Nazaré, five years after Dino’s outreach, and got a glimpse of the biggest wave he’d ever seen, he concluded that, towed in on a jet ski, he might manage to ride it. At the height of his enthusiasm, he got an email from the celebrated surfer Kelly Slater saying that he often went to Nazaré to surf the smaller waves and “to meditate and feel the power of the sea.” This 11-time world champion added a dire warning, One mistake and you might not be coming home.

**********

Making a Monster

The giants that pound Nazaré are created by a unique mix of fierce winds, a strong current and the largest submarine canyon in Europe.

“Oh, my God, I found the holy grail,” Garrett remembers thinking, as he saw the succession of waves. “They were 80 feet, minimum—some could have been 100. But they were so battered by the wind they had no defined shape.”

Ragged, foaming giants marching toward shore, they were unridable, but still Garrett watched in awe. And a week or two later the wind dropped, the waves were glassier, many of them “A-frames,” in surfer-speak, and Garrett began surfing Nazaré. He was 43—“physically and mentally prepared”—and rode a 40-foot wave, to the delight of some locals, but not to all of them.

Many people in Nazaré turned away from him, which seemed odd to the newly arrived American in a country famous for its hospitality and warmth. “They didn’t want to know me,” Garrett says—open-hearted himself, this chilly response disturbed him. He kept surfing on the first visit, but only the other surfers took to him—and the widows, the working people and others kept their distance. The fishermen were stern-faced, warning him of the wave, advising him against riding it.

Only recently, after his book appeared, did Garrett learn why so many good people in Nazaré seemed unfriendly. “They didn’t want to be close to me, because they felt I was going to die,” he says. “They lost people every winter. Everyone you meet in Nazaré knows someone who died—and especially died in a wave, within sight of shore.”

Garrett trained. “I wanted to become one with the land and the sea.” He researched the sea conditions, talking extensively to watermen and the body-boarders who had caught smaller waves at Nazaré (no surfers had attempted the giants). No longer the kid who smoked a joint before paddling into Banzai Pipeline, Garrett soberly traveled to Lisbon to discuss his plans with the Marinha Portuguesa, the Portuguese Navy. With almost 1,000 years of maritime experience (they won a great battle in 1180 down the coast from Nazaré, at Cabo Espichel) this venerable navy provided charts of the ocean floor and offered Garrett encouragement as well as material support, to the extent of placing buoys along the Nazaré Canyon approach.

This planning and training took a year, and reflecting on it you have to conclude that this was how the English Channel was first swum, and Everest was climbed, and how Amundsen skied to the South Pole: Such challenges were the subject of extensive research and contemplation before the first move was attempted. And this is also why I think the story of a 44-year-old man, strong but slightly built at 5-foot-10 and 170 pounds, is inspirational—and given the ups and downs of his personal history, an amazing trajectory.

To a non-surfer, a sea of breaking waves is one thing—lots of frothy water. To a surfer it is much more, a complex of breaks, of lefts and rights, and insides and outsides, each wave with a personality and a peculiar challenge.

“There’s so many different types of waves,” Garrett told me. “In Nazaré, it’s never the same wave—there are tall ones, round ones, hollow ones. In Tavarua, Fiji and in Indonesia, there are barrels. In Namibia, you can get barreled on some waves for three minutes.”

Measuring the height of a wave is another thing. “How tall is the wave you’re looking at? It’s not an exact science. One way is to look at the guy on the wave. How tall is the guy? Scale him with the wave. Figure out where the top of the wave is, where the bottom is, using a photo.”

To be ranked officially, the surfer submits a photo of the wave to a panel of judges in the World Surf League. “There are branches all over,” Garrett says. “Honolulu, New York, Santa Monica. They determine the height.”

(Read about efforts to engineer the perfect wave)

**********

Studying the waves at Nazaré, Garrett began to differentiate them. There was First Peak, which broke right and left in front of the lighthouse. “It’s fat and falls—it doesn’t break top to bottom. It caps at the top, so it’s hard to measure.” Near it is Middle First Peak, breaking left—“The magic, luckiest wave—it’s hollow and long, and it breaks top to bottom, so it’s measurable.” And beyond that is Second Peak, a big wave that breaks right and left. Farther to sea is the wave they came to call Big Mama or the Big Right—a monster. “It has to break three kilometers out, to be safe.”

On the 11th day of the 11th month of 2011 (“And Nicole says it might have been 11 in the morning”), Garrett was towed into the break at Middle First Peak and caught several big waves, bumpy rides that tested him. “I got pounded—but I was surfing Nazaré, and I was happy.”

The next morning he was woken by pounding on his door: “Garrett, it’s big!”

But he hesitated, thinking: I am not going for a record. I’m going out for the love of it—for the right reasons. And though he brought his board, he was the man piloting the jet ski, towing a surfer. He put the surfer on a wave and backed off, sliding sideways in time to see the man lose his board. And that wipeout had him thinking, maybe this is the one for me. So he switched places and grabbed his own board and was towed out, where he prepared himself, performing what yoga practitioners call pranayama (breath regulation), and what Garrett calls “a breathe-up.”

“Sitting on the board I did my breathe-up. It’s a complete reset. I breathe all my air out, I then fill my lungs with air while I’m looking toward shore, and I connect to the highest tree,” he says. “Then I looked back, out to sea, and I saw it swelling—really big—and I want to be in the barrel.”

He released the tow-rope and turned at the lip of water, his feet locked into the loops of the board. And set its edge on the biggest wave he’d ever ridden, and for the longest drop he could remember he was skidding in a monumental glissade down the face of this mountain-slope of a wave.

“I went straight to the bottom, and I punched it as hard as I could at the bottom, and I surfed straight back up and my speed pushed me in front of the wave.”

There was joy in Nazaré. The wave was submitted for measuring and proved to be 78 feet, a world record, officially the biggest wave ever surfed.

“You conquered the wave, Garrett!” became a frequent cry.

But Garrett shook his head, denying any such thing. “I complimented it,” he said. “I paid my respects,” and in this humility he is echoing the sentiments of the sherpas, when they finally attain the summit of Everest, known to them as Chomolungma, Goddess Mother of the World.

Why do surfers chase the biggest waves? Andy Martin, a lecturer in French at Cambridge University, and also the author of a surfing book, Walking on Water, has a theory.

“Big-wave surfing is an extrapolation of small-wave surfing,” Martin told me, “but Garrett is the fundamental paradox. There’s a passage in Sartre’s Being and Nothingness that always strikes me as being about surfing. Sartre speaks of “le glissement sur l’eau”—sliding on water—and he contrasts it with skiing, le glissement sur la neige, which leaves tracks in the snow. You imprint your signature in the snow. In a sense, you’re writing in the snow.

“But in surfing no one can find your tracks. The water closes over your passage. ‘The ideal form of sliding is one that leaves no trace.’ But now the culture has been absorbed and there’s a record. This is where Garrett’s record comes in. He’s staking a claim. He wants to be remembered. He wants someone to bear witness.”

**********

A year passed, during which Garrett continued to train in Hawaii, and in 2012 a new sponsor, Mercedes-Benz, commissioned one of its renowned designers to create the ultimate big-wave board. This man, Gorden Wagener—now nearing 50, around Garrett’s age—is responsible for the beauty of the Mercedes-Benz car design, sometimes referred to as “sensual purity.” Wagener applied both his aesthetic and his science to a surfboard. Wagener, who studied at the Royal College of Art in London, is both a surfer and a wind-surfer, and he has designed, built and shaped more than 300 boards.

“Garrett is a great guy and an outstanding athlete,” Wagener told me. “I think he is fearless and a little crazy in a great way. But you have to be in order to surf these kind of waves.”

“This board is a science project,” Garrett says, full of admiration for Wagener’s design. “It utilizes technology for survival.”

“Big-wave tow-in boards are the complete opposite to normal surfboards,” Wagener says. “They are narrow and heavy instead of wide and light. The shape is very similar to shapes we use in cars and of course we have computer tools to design basically everything. Important for us was also the corporate design—we created a ‘Silver Arrow’ of the sea—the Mercedes of all surfboards.”

At 25 pounds, of which 10 pounds is a slab of lead, and also formed of carbon fiber and polyester, the board is heavy, its forward third flexible, with a narrow PVC spine for shock absorption, and two parallel foot straps.

This was the board Garrett sat upon in November 2012 on the break he named First Peak in Front of the Rocks. He rose and fell in the channel in the winter sea for half a day, holding the tow-rope, his surfer friend Andrew Cotton on the jet ski.

“And then I saw it—a mountain coming down the canyon—the biggest swell I’ve ever seen—bigger than last year’s.” His eyes flash, recalling the sight. “I was excited. I had been envisioning this wave for a year, all through my training.”

And then he released the rope and tipped himself into the great slope of the wave and saw something he had never seen before on any wave: the face of the wave so furious and upswept that the wave he was coursing down was itself rippled with six-foot chop—like moguls on the black-diamond run of a ski slope.

“The waves in the middle of that wave were the kind that most surfers would be afraid of,” Garrett said, and the wave itself he guessed was much higher than the record wave he’d surfed the previous year. “So I’m going down, hunting for the sweet spot, when I can line up to get into the barrel.”

The wave began to break, then it backed off, and Garrett in retrospect estimated his speed at between 60 and 70 miles an hour.

“The most massive swell I’ve ever ridden, the fastest I’ve ever gone—I could barely control my board, but luckily it was this new board that had been made for me and for this wave. Even so, it was pretty much just survival.”

Yet the wave did not break, and seeing that he was speeding almost out of control, 20 feet from the rocks, he kicked out just as the rocks loomed. Then he was struggling in the water, on the board paddling. As the “safety ski” intending to pluck him aside was pounded by the wave, Garrett swam under (“or I would have been crushed on dry rock”) and fought away from shore and was grabbed by another ski and towed to the channel.

Shaking his head, Garrett says, “It was the closest I had ever come to death.”

**********

Although he had satisfied himself with the experience, the town of Nazaré was eager to enter Garrett’s ride in the record books. Garrett pointed out that the wave had not tipped and broken: It had been a moving mountain, easily the 100-footer he had sought all his surfing life. But he pulled the wave from consideration for the World Surf League’s XXL Biggest Wave Awards.

“I did not go out that day and surf for a world record,” he says. “All I wanted was to feel what it was like to ride that wave.” That the wave was known as Big Mama was an irony for a man whose own mother had been elusive; and it was also redemption and something to celebrate.

Many photographs were taken that day, and though an oceanographer might debate the absolute size of this wave, you only have to compare the man, and his board, with this massive wall of water behind him and under him to conclude there can be little doubt that Garrett had found his ultimate ride, and become a happy man.

Nazaré too became happy; and the people in town who had avoided him out of fear of losing him now embraced him. Two years earlier there was scarcely one person standing on the cliff near the lighthouse, and soon there were thousands, and on an average winter day they closed the road because they could no longer accommodate the traffic.

“McNamara is well known in Portugal—and in Nazaré in particular—since he surfed that 24-meter wave in 2011,” says Ana Roque de Oliveira, an environmental engineer and photographer based in Lisbon. “He was smart enough to interact with the local population—which is not common in Portugal—so the benefits were mutual. And Nazaré being a small town, news traveled faster.”

The town basked in its reflected glory and enjoyed a measure of prosperity. Portugal, never regarded as much by surfers, became a great surfing destination.

And—just as I was finishing this piece—a Brazilian surfer, Rodrigo Koxa, was told by the Quiksilver XXL Big Wave authorities that the wave at Nazaré he had ridden in November 2017 was assessed at 24.38 meters, or 80 feet—and Garret, a friend, who had told him about the moods of the Nazaré wave, was among the first to congratulate him.

Along the way, Garrett, the modest, middle-aged man from Hawaii, became a national hero. In many respects, he is the man from nowhere—from poverty and random parenting; but the hardships of his childhood, which might have broken someone else, made him strong. His is of course a story of courage, but it is also a story of preparation and self-belief.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/0c/e60c06a7-43f6-4737-a9d6-bdb1736fa35d/julaug2018_h06_bigwave.jpg)