The Rise and Fall of the Plane “Anyone Could Fly”

It was billed as the “Model T” of airplanes. So what happened?

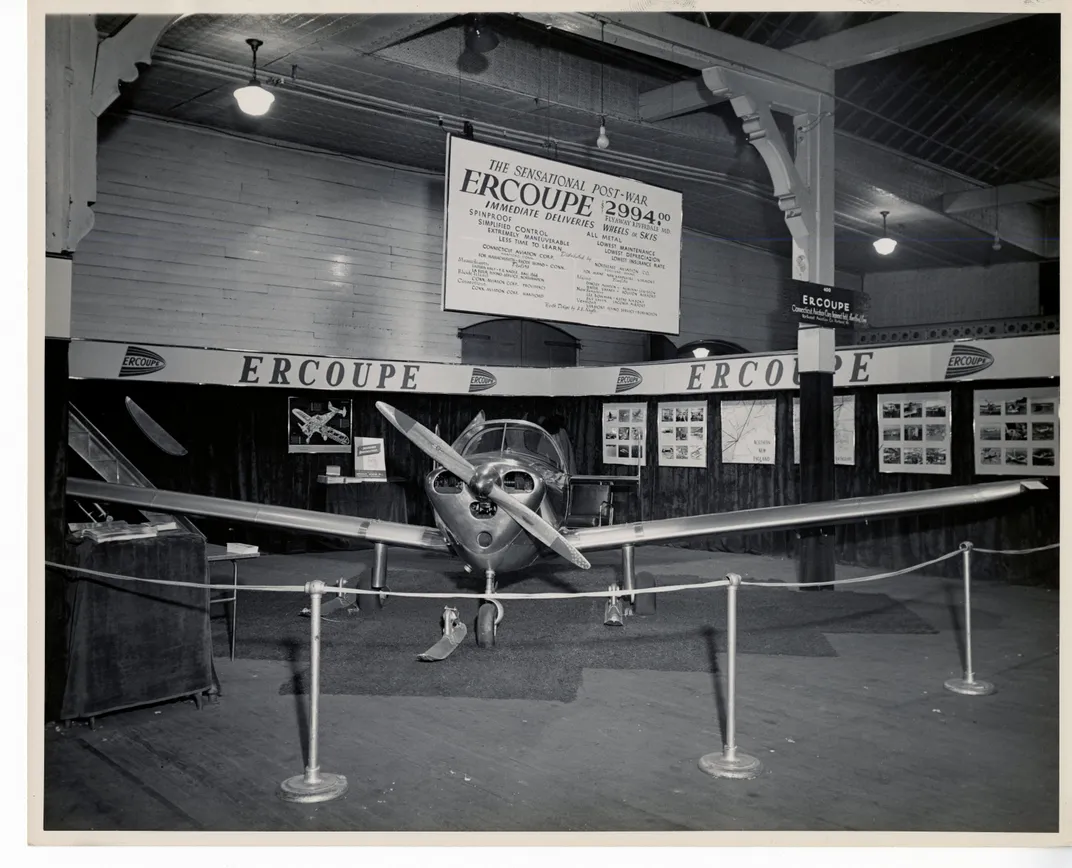

In October 1945, the future of travel sat in a glistening showroom in a Manhattan Macy’s. Alongside the department store staples of household appliances, gentlemen's socks and ladies’ girdles was a small, all-metal, two-seater airplane. This was the Ercoupe, “the airplane that anyone could fly.”

Built by the Engineering and Researching Corporation (ERCO), the Ercoupe was billed as “America’s first certified spin-proof plane.” It was safe: Ads called it the “world’s safest plane” and compared its handling to that of the family car. Others vouched for its affordability, emphasizing that it cost less than $3,000 (about $39,000 today). It was also a media sensation: LIFE Magazine called it “nearly foolproof” and the Saturday Evening Post asked readers to not look at it “as another airplane, but as a new means of personal transportation.”

It was the “plane of tomorrow, today.” But by 1952, the Ercoupe was basically out of production. Seven decades later, the question remains — what happened?

The answer can be found at Maryland’s College Park Airport, a facility recognized as the “world’s oldest continuously operating airport.” Located only ten miles from downtown Washington D.C, it's where Wilbur Wright first taught military officers Lt. Frank Lahm and Lt. Frederic Humphreys how to fly an airplane. The College Park Aviation Museum, which overlooks the airport’s runway and house the ERCO company's archives, features a new exhibit highlighting the glitz and glamour of the forgotten aircraft.

The story of the Ercoupe begins with aviation pioneer Henry A. Berliner, who founded ERCO in 1930. Perhaps best known for developing a practical helicopter with his father, Berliner envisioned a future filled with accessible air travel. In 1936, he hired engineer Fred Weick, who shared his lofty ambition to develop an easy-to-fly, consumer-friendly aircraft. Later, Weick’s daughter would say that her father’s goal was to build “the Model T of the sky.”

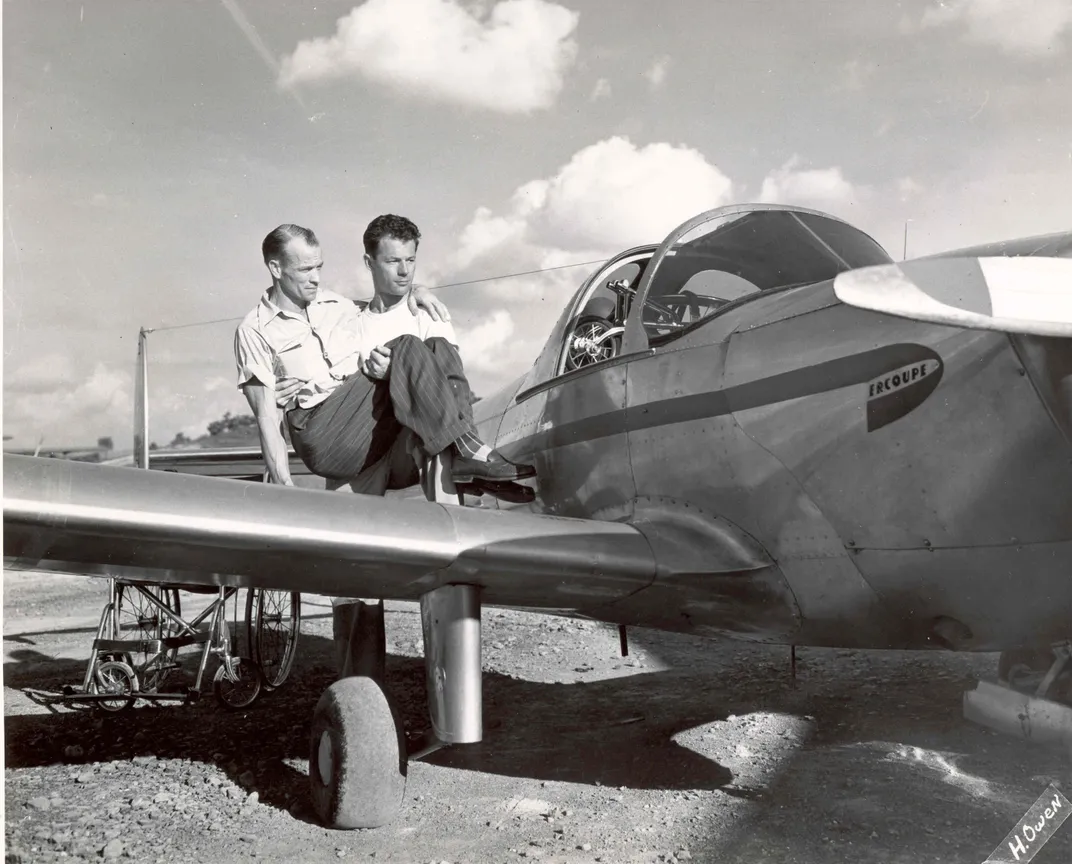

With that in mind, the Ercoupe was born. The first production model was completed in 1938 (an early model can be found in Smithsonian’s collections), and it was unlike anything ever crafted before. It steered like a car due to the nose wheel being connected to the control wheel. It featured triangle landing gear, an innovation still used today. Most noticeably, though, the Ercoupe was rudderless, meaning the plane was flown entirely through the control wheel. When the Civil Aeronautics Administration decreed that the plane was “characteristically incapable of spinning” in 1940, it was clear that the Ercoupe had earned its famous moniker: “the plane that flies itself.”

The Ercoupe was poised to be a flying sensation, says Andrea Tracey, director of the College Park Aviation Museum. “Even though aviation was only about 30 years old at the time,” she says, “anyone could have and learn how to fly” the Ercoupe. Its accessibility was the secret of its early success, she notes: “You could order it from Macy’s and J.C. Penney, just like you could have ordered a house through Sears Roebuck.”

For a while, the plane even seemed to be impervious to world events. Though ERCO only manufactured 112 airplanes before the looming war effort halted production, it started selling the plane as soon as World War II ended. By the end of 1945, the airplane was in department stores across the country – from Denver to Baltimore, from San Antonio to Allentown. Celebrities like Dick Powell and Jane Russell bought and endorsed the airplane. The Secretary of the Interior Henry Wallace flew an Ercoupe solo. Magazine and newspaper features were written highlighting the safety, accessibility and affordability of the Ercoupe.

ERCO’s marketing blitz worked: During the first year, the company took over 6,000 orders. To keep up with demand, Berliner increased production, firmly believing the boom was here to last. By mid-1946, the ERCO factory in Riverdale was producing 34 airplanes a day.

Then, it all fell apart.

The Ercoupe’s journey from boom to bust happened seemingly overnight. First, production outpaced demand. A brief economic downturn in 1946 spooked would-be purchasers. And professional pilots voiced their suspicion of the plane, pointing out that while the plane was safe in the hands of an experienced operator, descents and speed drops could prove to be fatal for the average consumer.

In the end, only 5,140 Ercoupes were produced. Just two years after taking America by storm, Berliner sold the rights to his plane. Seven years after it was introduced, production of the plane ceased for good.

Today, only about 2,000 Ercoupes still exist (only about 1,000 are registered to fly with the FAA). Chris Schuldt flies his Ercoupe three or four times week, usually making short trips from his home in Fredericksburg, Virginia. He says the plane still gets fellow pilots talking. “You can never land anywhere where someone doesn't come up and ask you about the airplane,” says Schuldt. “They are a real conversation piece.”

Schuldt, who has had his pilot’s license since 1996, says the Ercoupe is relatively simple to learn. But, like pilots of yore, his enthusiasm comes with a caveat. “90 percent of the time you can teach someone how to fly this plane much more easily and simply than many other airplanes,” he says. “The only problem is that last ten percent: It’s the ten percent that will kill you.”

Maybe it was the danger. Maybe Americans just weren’t ready to buy a plane along with refrigerators, underwear and the “miraculous” ballpoint pen. Ultimately, the Ercoupe wasn’t the plane for everyone — but it still represents a soaring vision of what travel could have been.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.