The Everlasting, Awe-Inspiring Power of Alaska

For 150 years, Alaska has been a part of the United States, and it’s never ceased to amaze

At 4 in the morning on March 30, 1867, Secretary of State William Seward signed a treaty buying Russian America—that is, Alaska—for the cost of two cents per acre, a total of $7.2 million in gold bricks. After weeks of talks, a Russian diplomat had called at his house at 10 p.m. to say that Russia would sell the next day. “Let us make the treaty tonight,” he replied. The deal was almost universally hailed as a step toward increasing trade routes in Asia and full American possession of the Pacific Coast. Only years later did it come to be known as “Seward’s Folly,” a vast and worthless snowscape.

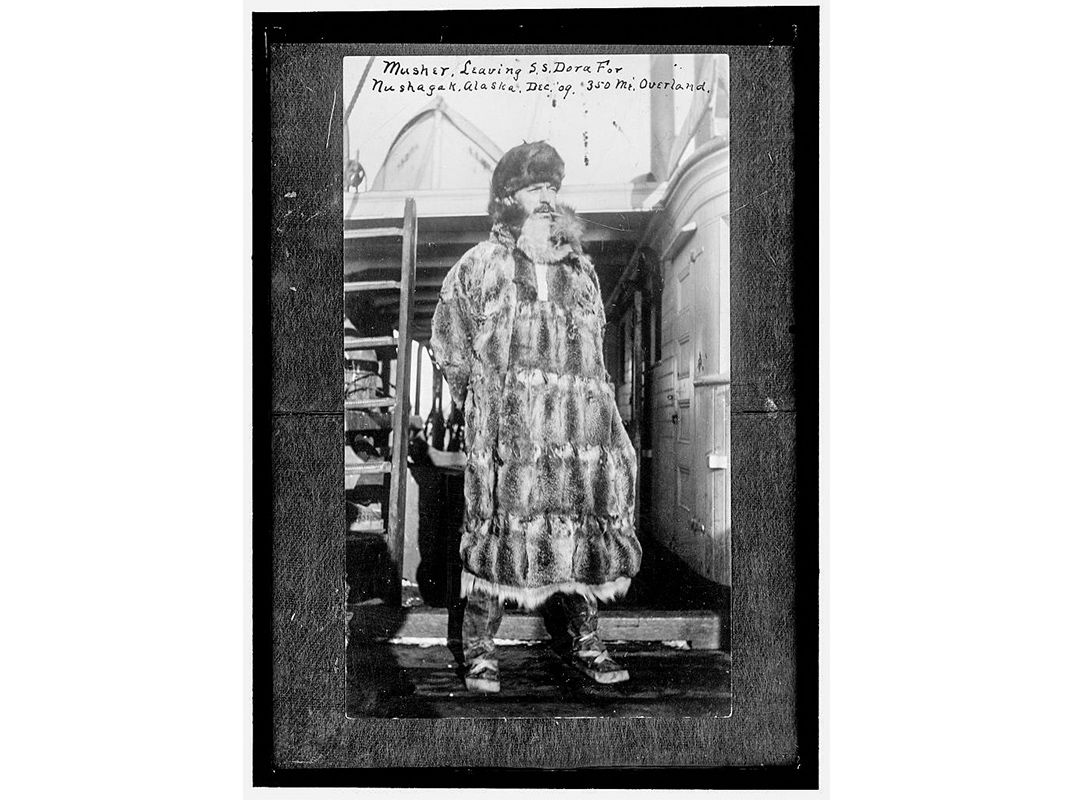

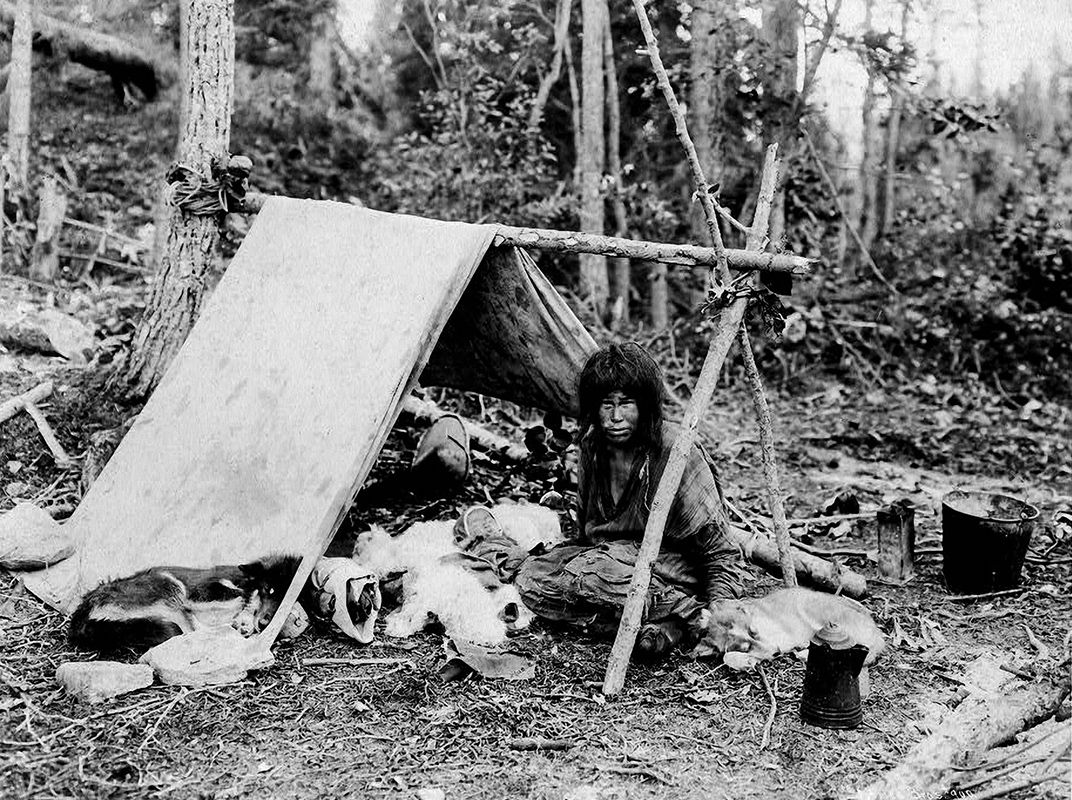

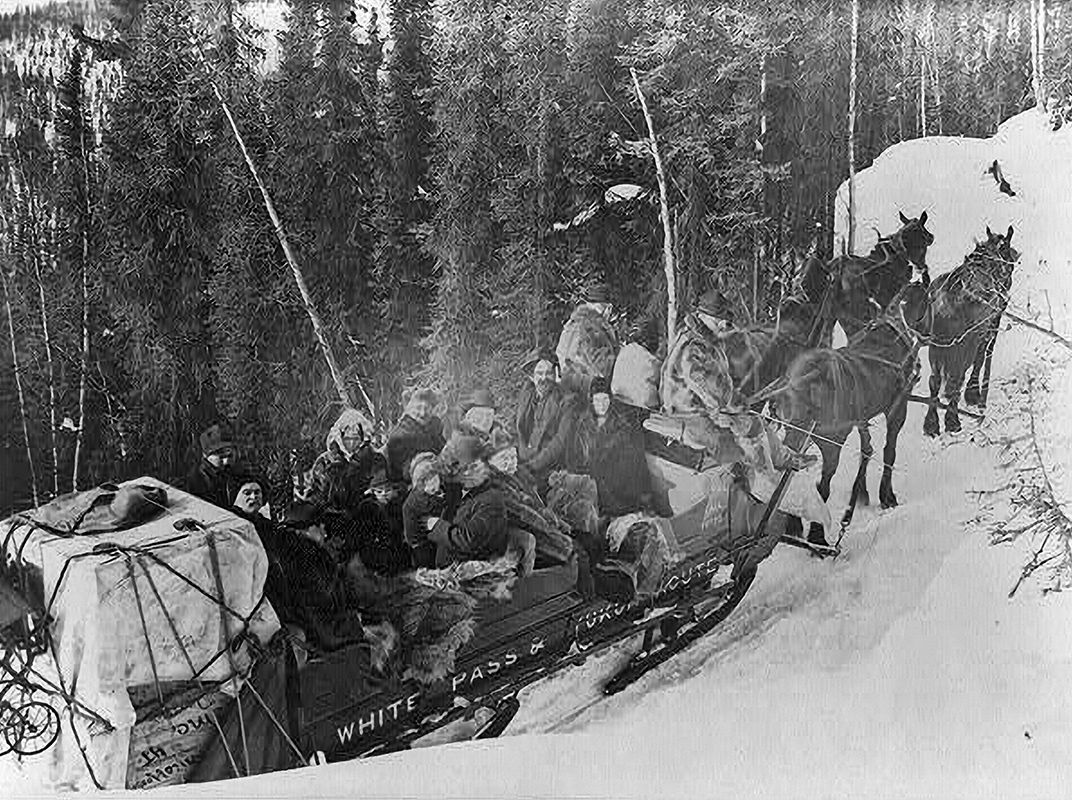

In time, of course, it would prove just the opposite, a jackpot where money comes out of the earth. Even more important to Americans’ sense of themselves, though, Alaska has always been a Last Frontier, to be conquered by everyday heroes wielding a pure white masculinity long since dissolved in the lower 48. (No matter that native communities have lived there for 15,000 years.) Within three decades of its purchase, American optimists settled in Sitka, the renamed former Russian capital, and most Russian citizens returned to St. Petersburg on overcrowded merchant ships. After a trapper named George Carmack spotted a nugget glinting in the waters of Rabbit Creek in the summer of 1896, a hundred thousand prospectors surged north for the Klondike gold rush. That winter, riverboat fare from Seattle to Dawson City, in the Yukon, spiked to $1,000, or about $27,000 today. Hopeful fellows with less means—which is to say, most of them—set out hauling sledges with months’ worth of food and clothing, gambling on how to pack to survive in temperatures down to minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit. They carved staircases into the icy mountainsides, built rafts that shattered in the Yukon River; some took to frozen waterways on bicycles and ice skates. In the final decade of the 19th century, Alaska’s population doubled. Only 8 percent of the newcomers were women. Only 4 percent struck gold.

When I was 19, desperate to be heroic, I moved from California to the Norwegian Arctic, then to the south tongue of a glacier in Alaska’s Juneau Icefield to work as a dog-sled guide for cruise ship passengers. Most of the tourists I met had never been to Alaska before; the icefield stunned them, and me, into a state of childlike astonishment and occasional panic. Well-to-do people came to be reminded of the planet’s imponderable scale and wild dangers, and my job was to give them a taste of this wild extreme and then return them safely to ordinary life. In playing the Alaska insider, I glimpsed the scaffolding that holds up the myth. If I was acting, then what if everyone else was, too?

That sense of living in the midst of something overpowering gives Alaskans a particular kind of pride. Forget the fields of fireweed and paintbrush, the soft yellow light of the midnight sun that show us the state’s gentler side: These things exist for us primarily to contrast with the bitter cold and mustache icicles, the battles against nature that rescue residents from the softness of urban living.

It’s also a land where 48 percent of women have reportedly suffered domestic violence. And the more that Alaska’s cities are built up on money that flows from Prudhoe Bay’s 25-billion-barrel oil field, the less daily life looks like something out of a legend. Yet the mythology remains.

All the same, the realities of Alaska—the idea, the people, the stories—still grip me enough that, almost ten years after leaving the state, I’m training for next year’s Iditarod, the 1,049-mile dogsled race from Anchorage to Nome. It may not be “The Last Great Race on Earth,” as it calls itself—there are other dog-sled races that are considered harder—but that’s OK. Like Alaska, it doesn’t need to be the greatest in order to be great.

The folly of Alaska was never Seward’s—by any measure he made a brilliant bargain—but ours, for ascribing meaning to an indifferent landscape, and then for romanticizing that indifference. We bought it, but it has never been ours.

Related Reads

Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube: Chasing Fear and Finding Home in the Great White North

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.